The reality of the pandemic descended upon me during a Guns n´Roses concert in Mexico City. The date was March 14th. While Mexico hadn’t yet formally declared any confinement measures (that would happen on March 23rd), the pandemic was well advanced throughout the world and many bands cancelled their participation in one of Mexico’s biggest rock festivals, the Vive Latino. Not Guns n’Roses, the headliner of the festival. It was an amazing gig, played to some 40,000 people. In the middle of each and every song, Axl would run off stage, maybe to let the band shine, maybe to drink, who knows. Before “November Rain”, he mentioned there was a problem with his piano and they had had to replace it with a new one: “Maybe my piano has coronavirus”, he quipped.

The festival went ahead as usual, though it was much less crowded than other years. Temperatures were taken at the gate. A friend of mine who used to front a band called Liquits invited me with a special guest pass, and at first, backstage with other rockstars, there were no handshakes, but joints would be shared freely. As the evening advanced and the beers accumulated, the cautionary measures eroded and, at the end, were non-existent, with everybody in our group drinking from the same glasses.

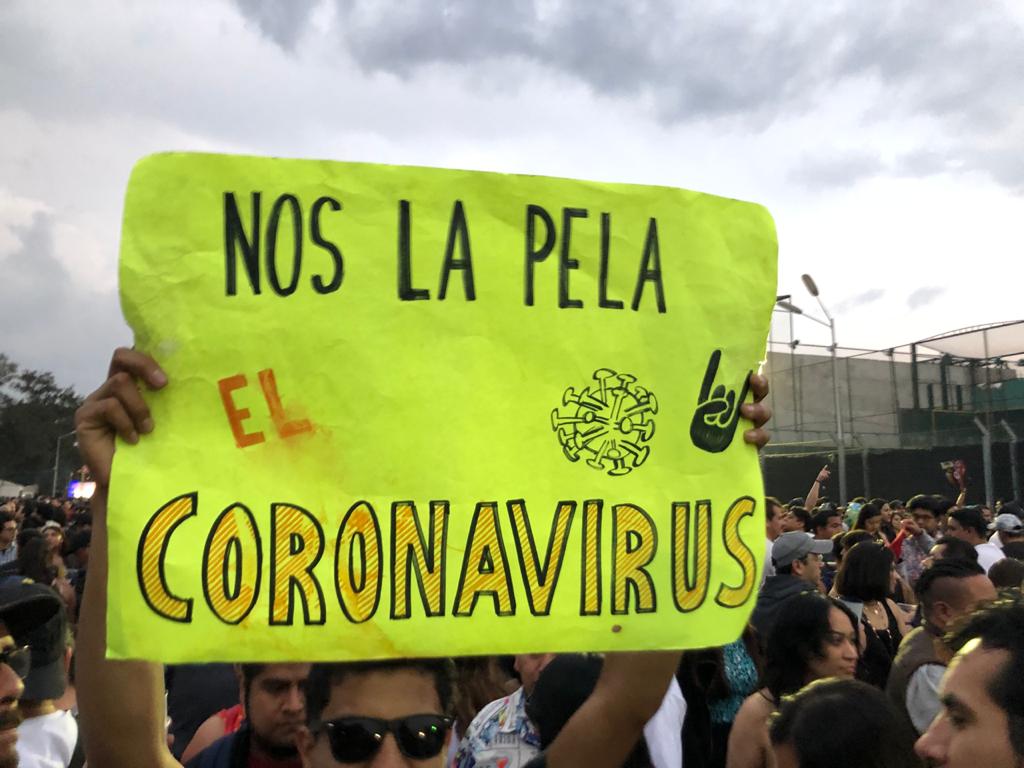

There was an outcry on social media about the festival having taken place, both against the authorities and the attendees. A kid that walking through the festival carrying a sign that read “El coronavirus nos la pela” – untranslatable slang which means something like “Coronavirus won’t do shit to us”, only with a sexual implication – was particularly roasted on social media. As time passed, however, it became apparent that there hadn’t been any significant transmissions at the event.

***

The first registered coronavirus death in Mexico occurred on March 18th. It was a 41 year old man who was severely overweight and had diabetes (Mexico is the 9th most diabetic country in the world, with an estimated 100,000 deaths from it every year). At first it was reported he had attended the Vive Latino festival, but then it turned out he had probably contracted the virus on March 3rd, at a massive concert in Mexico City of the Swedish band Ghost, whose frontman always appears on stage wearing a death mask.

***

On March 23rd, the lockdown formally begins, with what is called the National Safe Distance Period, which will end up lasting until June 1st, when the New Normality, which everyone is still trying to figure out, kicked in. From the first day, Mexico’s coronavirus czar, a public servant from the Health Ministry called Hugo López-Gatell, begins holding a daily press conference at 7 pm, broadcasted live from the National Palace, in which he and various aides provide an update on the pandemic, and take questions from reporters. From the beginning, it became must-watch TV, and it’s commonly referred to in playful manner as the “7pm soap opera”. López-Gatell is widely considered an eloquent and articulate public servant (features that strongly oppose Mexico’s long-standing tradition of bureaucracy, incompetence, corruption and opacity); has even become a sort of sex symbol, and has been invited to participate in a panel of experts on coronavirus policy put together by the WHO.

In stark contrast, his boss, president Andrés Manuel López Obrador, while effectively giving López-Gatell the capacity to make scientifically-oriented public policy decisions regarding the pandemic, has often undermined the seriousness of it. As late as the end of March, he was still hugging and kissing supporters publicly during meetings, including an eight-year old girl. During his own daily press conferences, he also implied that he was protected against the virus by his honesty and his anti-corruption ethics, and he showed two amulets that worked as his “protecting shield”. He’s also declared that the economic crisis and ensuing government austerity programme caused by the lockdown fitted his political project ‘like a glove’.

And, without a doubt worst of all, when questioned about the statistics of the increase in domestic violence against women as a perverse side-effect of the confinement, he stated that most of the calls for help made by women to emergency numbers were fake, saying that Mexican family values are a safeguard against such violence. All of this, in a country with one of the highest rates of gender-related violence, with 10 women murdered on average every day. His government also released a much rejected campaign on the subject, urging potential aggressors to “count to 10” before engaging in violent acts, which had to be removed and was condemned by Mexico’s Human Rights Commission.

Now, with the country still mostly in lockdown, he has resumed his political tours throughout the country.

***

On March 31st, I get fired from Sexto Piso, the publishing house I founded with some friends on 2002, as the survival of the company during the pandemic, with bookstores shut and bookfairs cancelled, looks extremely difficult, so the founding members who still work there, decide to fire ourselves in a cost-cutting move, to try and keep the rest of the staff employed.

Since 1997, pensions have been privatized and standardized in Mexico, so that each worker has a portion of salary taken and saved into an individual retirement fund, which can be public or private, and use investing (even in the stock market) as a way to increase the pension pot, which in some years results in “negative earnings” for the workers. Thus, when you retire, you have saved an x amount, which you can then dispose of as a pension, but not before. However, there is an unemployment insurance, which allows you to dispose of a certain amount of your retirement savings in the event you are out of work, and you can do this only once every five years. But first you have to wait 46 days since you have become unemployed to file for it, so I wait the corresponding time. Then the Kafkian odyssey begins.

Since my first employer was the National University more than 20 years ago, my pension plan is handled by PENSIONISSTE, which is the agency that manages the retirement plans of public-sector workers. I have to register in their web page to be able to consult my balance, but since my CURP –which is an identity number that the government assigns to every Mexican citizen– is duplicated, the system doesn’t recognize it… until one day it does. I then reach a page that I haven’t been able to get through after more than a month of trying it every day, in which, I guess because they need to verify that you are the actual account holder, they ask you a question related to your employment history. Every time I try to answer, the page gets stuck, and you can only try once every 24 hours. The last few times, some of the options to answer the questions have begun to appear in Portuguese.

Due to the pandemic, PENSIONISSTE is only handling applications with a previous appointment. However, if you call the number to get an appointment, no one answers. There is also a section on their web page to have your questions answered through a live chat, which at the moment is deemed as “under construction”, with a drawing of a working man holding a shovel.

It doesn’t really matter, as in order to file my application in PENSIONISSTE’s offices, I first have to get an official unemployment certificate by the Public Health Ministry, the IMSS, which, again, one should be able to get online. However, my application states that there is something wrong with my information, so I should go to my corresponding office to get it sorted out. I do so, and the woman in charge tries to do exactly the same as I did, get the certificate online in her computer, which the system doesn´t allow. She sends me to see a man who has a higher position, who tries again to do the same thing, with the same result, and suggests that the problem might be that the internet connection isn’t very good in their offices, so I should go to the street and try to do it again in my cell phone, which I do. I come back, a failure, and the man is perplexed and says he can’t think of anything else to do, except wait a few days and try again.

I return after the few days have passed and we go through the same ordeal. The man then says he’ll give me a phone number which I should call to see if they can help me there. Before that, he says, I should try a procedure which is used to correct the personal information of the worker when there is a mistake on the system, so he hands me a four page form which asks for very detailed information. I go to the information counter and they say I should go to booth number 5, only better tomorrow, as it’s already 2:15 and the (empty) booth closes at 2:30.

I return the next day with my form filled, and proceed to booth number 5. The woman in charge orders me brusquely to make some copies of my documents (which, to her credit, I knew I should bring and had forgotten to do). I do so and upon return, as I’m trying to separate the pages that I should hand her, I slip my thumb under the facemask to lick it and make the task of separating the pages easier. The woman is not pleased about this, and reminds me of the prevailing health crisis. After she types information into her computer for about 20 minutes, she informs me that there is indeed a misspelling of my name which must be amended. This will take at least between 2 to 3 weeks, she informs me, so I should call after that to see if it’s been corrected, and I can get the document I need to file for my unemployment insurance. At this point, I just hope to be able to collect it before I reach retirement age.

Eduardo Rabasa

Part 2 from Mexico to follow soon