Thanks to my older brother, I was a pre-teen metal head. I can’t blame him though. Growing up in South Wales in the early ’80s, it was practically compulsory. These were the glory days of NWOBHM (New Wave of British Heavy Metal). Bands like Saxon and Gillan were regulars on Top of the Pops. The look was standard: bum fluff; a denim jacket – still too blue as it was never washed – covered in badges and patches; a visible lack of confidence when confronted with any member of the opposite sex. Metal made sense to kids like me. It was rebellion but not nihilistic in the way punk rock was; it came wrapped in just enough mystical cobblers to entice, in a Dungeons and Dragons kind of way and it accessible via local venues like Cardiff Sofia Gardens and Port Talbot’s Afan Lido. It was a touring culture and all of the greats passed through town on a regular basis. The smell of patchouli oil was intense on gig days.

I moved on from metal after an unplanned encounter with Morrissey on the Oxford Road Show. Suddenly, grown men in spandex trousers seemed ridiculous compared to a miserable chap with a hearing aid waving a bunch of gladioli over his head.

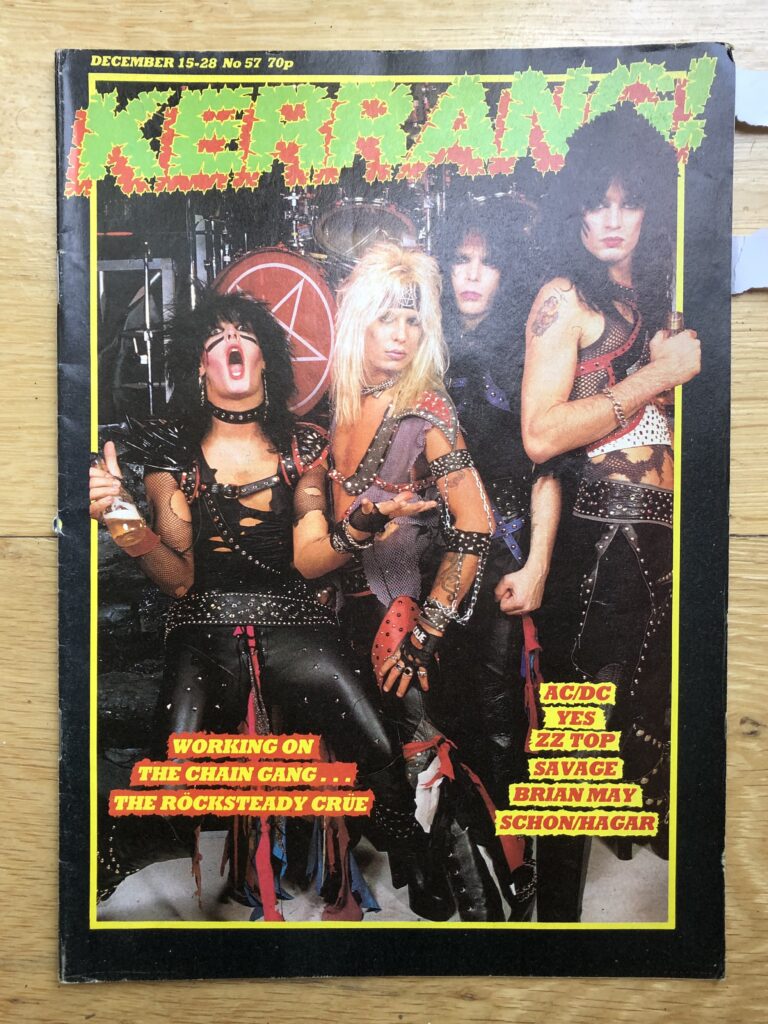

While I was looking elsewhere, metal changed without me. Bands began to look more and more incredible – less like brickies bulging out of every tight seam, more androgynous and primped up, like prostitutes who’d beat the shit out of you and rob your wallet without a second thought. Things changed lyrically too. Orcs were out. Fucking was very much in.

Thirty plus years after the late ’80s explosion of glam metal, its a genre that remains enigmatic – a weird blip in history that few will admit to having been a part of. When film director James Gunn (Guardians of the Galaxy 1 & 2, The Suicide Squad) posted an unapologetic tribute playlist to the glam era on his Spotify account last year, it seemed like a truly subversive act in the current musical climate.

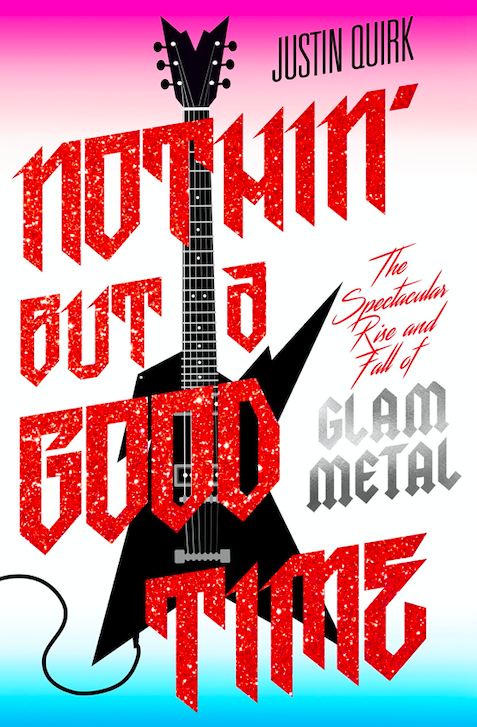

One person who will admit to having been caught up in glam metal’s tractor beam is author and journalist Justin Quirk. His newly published book Nothin’ But A Good Time aims to reposition things by giving it some long overdue respect. Named after the 1988 single by Poison, it documents the history of that often ridiculous metal scene but where many would sneer at the excesses and daftnesses of glam metal, Justin Quirk’s brilliant book is an unrepentant love letter to the music and the men behind it (let’s face it, they are mainly men) – bands like Def Leppard, Mötley Crüe, WASP, Skid Row Bon Jovi, aforementioned Poison and many, many more.

As the Social Gathering reaches for the hairspray, we asked Justin what made him decide to celebrate one of the most (unfairly) maligned genres of recent times.

Robin Turner

Social Gathering: When did you first fall under the spell of glam metal?

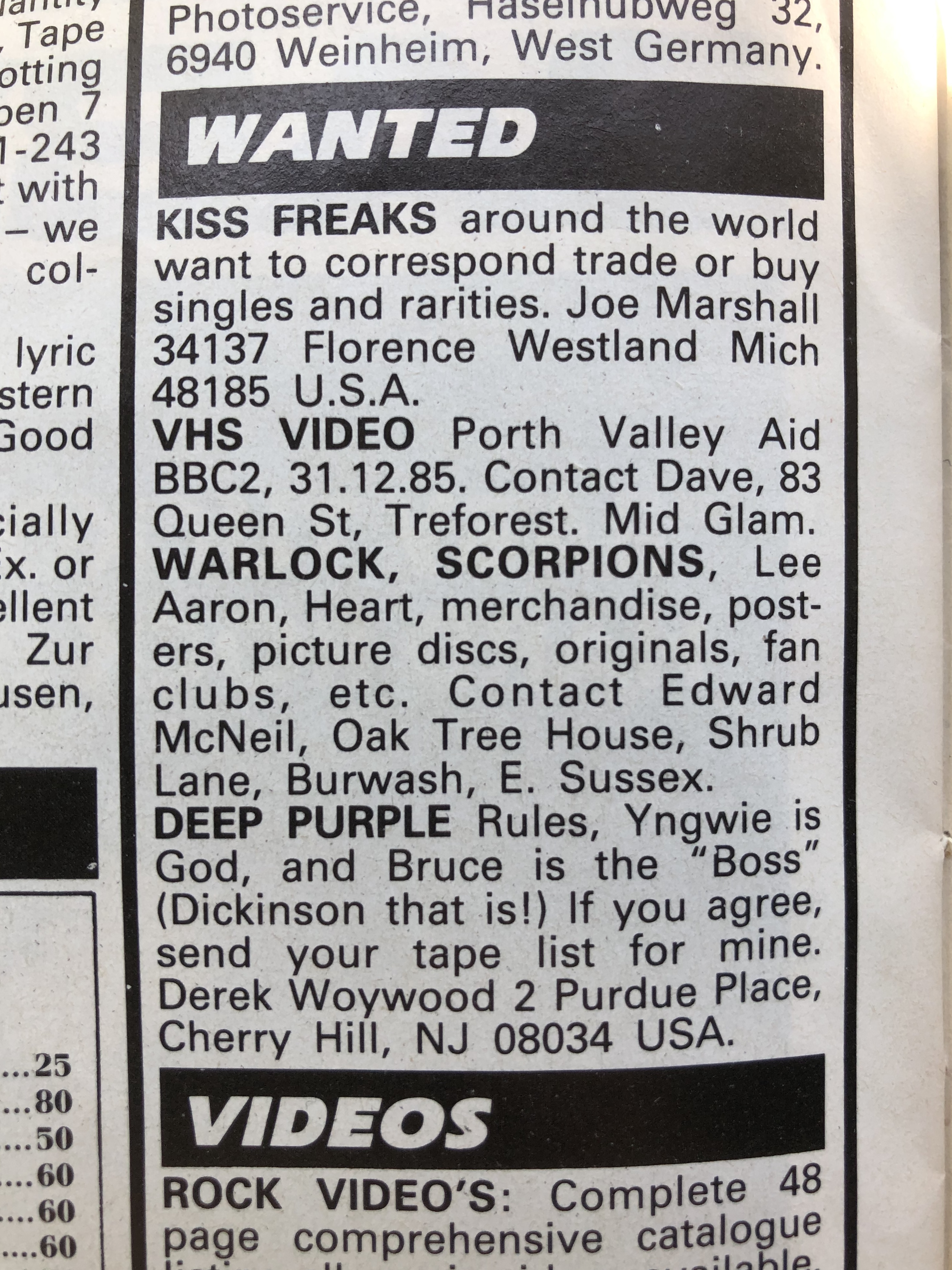

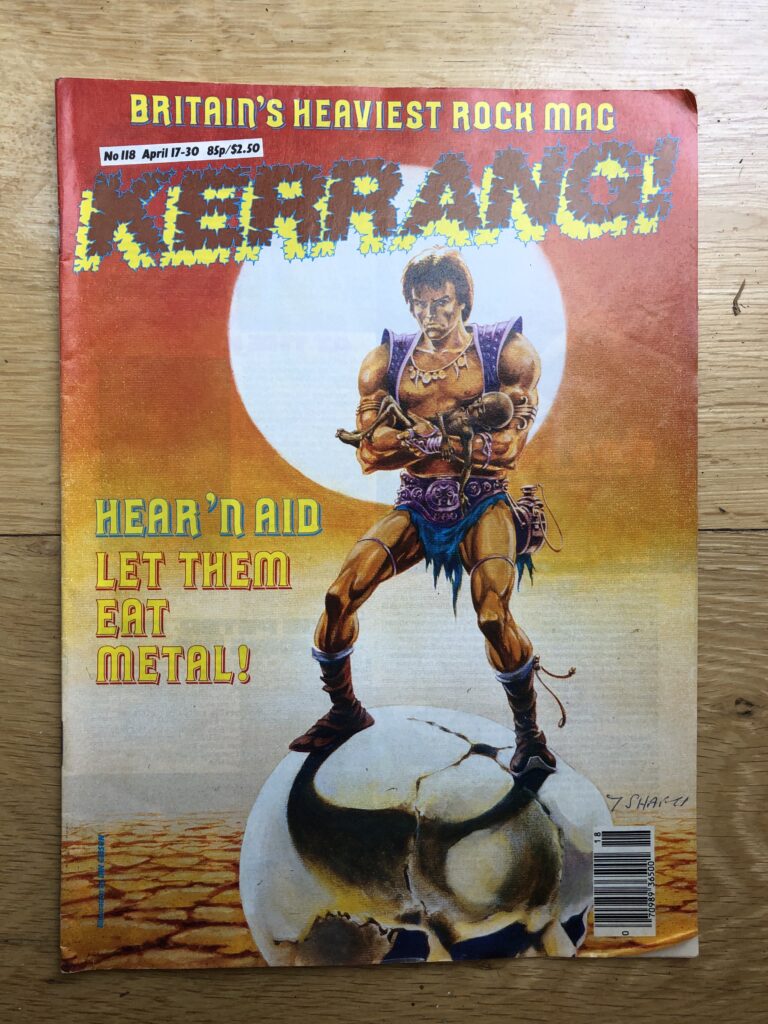

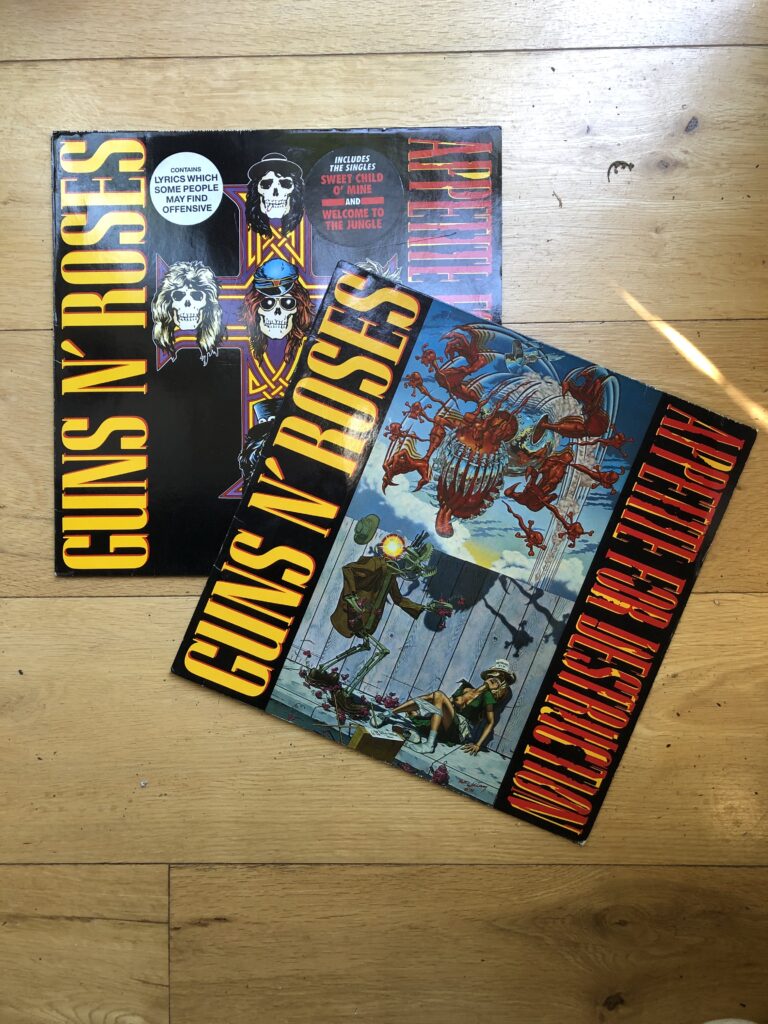

Justin Quirk: I was about 11 or 12 (’87-’88). I’d been into pop music and trying to amass my own records from a really young age – maybe 6 or 7 – but I definitely went full metal around that point. A load of things dovetailed. I started learning the guitar – buying magazines like Guitar World you were exposed to a load of artists you weren’t going to find in Smash Hits or on Capital Radio. And there was a 12 month period where ‘Hysteria’, ‘Appetite For Destruction’, Poison’s ‘Open Up And Say….Aah!’ and Aerosmith’s ‘Permanent Vacation’ all came out in quick succession. I was in the perfect place for this stuff at just the right time. The other important thing to remember – and something I touch on a lot in the book – is that this stuff was *way* bigger commercially than people remember. In terms of sales, it was completely mainstream. It’s what built MTV; Kerrang! was selling in huge numbers. There’s a week I saw while doing my research in, I think, 1987 where The Joshua Tree is Number 1, but pretty much every other album in the Billboard Top Ten is a glam metal album. These bands were showing up on Top of The Pops. For all the outsider trappings, it was pop music, really.

SG: It seems like a hard genre for a fan to replicate the look successfully. Did you adopt the uniform as a teenager?

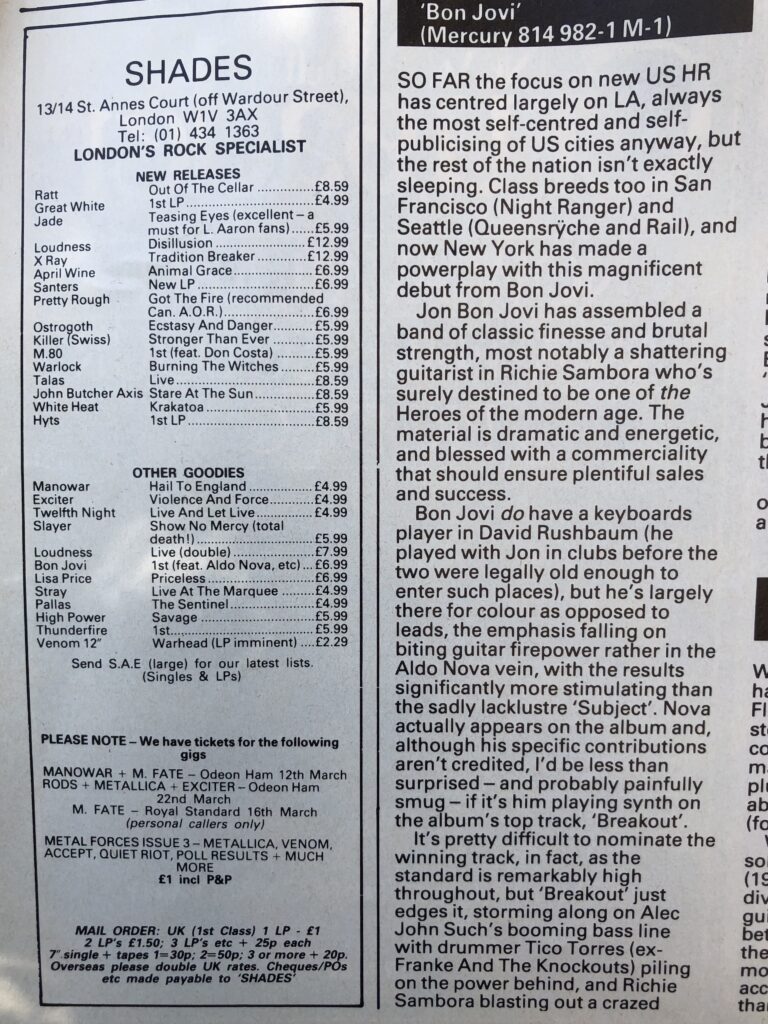

JQ: God no. Mainly because I went to a fairly rough comprehensive on the edge of Hanworth and I’d have been kicked to death in about 20 minutes if I’d turned up dressed as (Poison’s) CC Deville. Also, I was never able to grow my hair much past my collar, which is probably for the best with hindsight. It was a real commitment though as an image. You’d go up to places like Kensington Market or the shops on Carnaby Street or Shades, the record shop on St Anne’s Court in Soho and see these guys who were fully into it and even then you’d sort of think, ‘What do you *do* the rest of the time?’ I don’t know – I suppose it’s possible that you could turn up for work at the local council dressed like a member of Hanoi Rocks, but it seems unlikely.

SG: As a fan at the time, were you aware of the genre’s ludicrousness?

JQ: This is a really interesting question and it’s something I talk about in the book. I think glam metal knew it was ludicrous, but it took itself seriously. It was sincere. I think the big dividing line after glam metal and from grunge onwards is that everything comes with this layer of irony. It’s all very knowing. Glam’s very one-dimensional in a way. I think this is kind of what locks it in the past and means that it can’t really be revived. If you saw someone in a music video now dressed like Motley Crue you’d assume it was a joke, or a knowing reference to something else but those guys just dressed like that because they thought they looked good.

SG: What happened to make you move on from metal?

JQ: Guns n’ Roses releasing Use Your Illusion was a huge breaking point for a lot of people. It’s difficult to convey what a huge deal those albums coming out was. They had been the biggest story in metal for maybe two years? Endlessly delayed, so many rumours around it. Steven Adler leaving the group, the riots at their show in St Louis. They were such a huge deal. We had a pre-release bootleg of Use Your Illusion from Camden Market which was just the piano demos and it sounded great. Then we saw them at Wembley Stadium in 1991 – the last show they did with Izzy Stradlin – and they absolutely killed it. They were so good. So everything’s on course and then… the album comes out and it’s really not what anyone wanted. We desperately wanted it to be a classic – and it was hugely successful commercially – but it was just a mess. I think everyone knew it was game over. Then we saw them again at Wembley and they’d gained a horn section and backing singers and… it was pretty horrible, really. It just felt like the whole thing was shuddering to a halt. Def Leppard had come back but without Steve Clark and it wasn’t the same, Poison were falling to pieces. The guitar stuff which was interesting was getting much heavier and stranger with records like Faith No More’s Angel Dust. I left school that summer, bought a Dead Kennedy’s record from my local shop and went off down that rabbit hole. I started buying loads of stuff on SST, all those Blood and Fire dub reissues, got into the Beastie Boys. It just felt like a natural conclusion of things as that scene had come to an end.

SG: What would you say are the specific traits that make up a great glam metal band?

JQ: Being sincere about being ridiculous. Rock solid pop songs (there’s a reason why Taylor Swift and Mariah Carey cover Def Leppard). A drummer who can twirl the sticks, waggle his tongue at the camera when it comes near him. Pyrotechnics. A logo you can draw on an army surplus bag. A singer with a voice that can go really high. A guitar in an odd shape, preferably with more than one neck. A promo video featuring acts of mild rebellion against overbearing parental authority figures.

SG: How would you say they differ from the generation of bands that came before (New Wave of British Heavy Metal aka NWOBHM, early thrash bands)?

JQ: NWOBHM wasn’t pop in the slightest. The songwriting very rarely takes flight and even at its best (Paul Di’anno era Maiden, some of Saxon’s better stuff) it’s quite lumpy. It’s self consciously ugly. Thrash was much more blue collar, and kind of the anti-glam. Glam was much more tooled to include and appeal to women. Thrash and NWOBHM really weren’t.

SG: I loved the respect you afford the music – even the band’s that history would happily write off. Was that a conscious decision when setting out to write the book?

JQ: Absolutely. I always think that kind of writing is a bit of a cheap shot – and ultimately, it’s pretty unsatisfying to read. There’s obviously a rich seam of comedy to be mined from this music – I’d recommend Seb Hunter’s superb glam metal memoir, Hell Bent For Leather which is genuinely laugh-out-loud funny (as well as being extremely poignant and brilliantly observed – but that can’t be all there is to a book of this length.

SG: Do you think it’s unfairly maligned?

JQ: Absolutely. That was one of the things which first planted the seeds of the project: firstly, the fact that the genre was as huge as it was, and yet you *never* hear anyone say ‘I was a teenage Dokken fan’. Well, someone was. Where did all those people go? And on the critical side, I couldn’t see why almost every other genre is now allowed a serious reappraisal as being something which was culturally important. Simon Reynolds can write very seriously about the absolute bargain basement end of glam rock. Stewart Home has written brilliantly about the worst end of Oi! music. That Jeremy Deller film last year which everyone loved was essentially looking at a load of provincial ravers in fairly unglamorous nightclubs necking handfuls of E to ’Numero Uno’ or whatever. Now, I love all that stuff, but I couldn’t see why that was worth a serious critical unpacking, and something like ‘Hysteria’ wasn’t. And that was genuinely what I was trying to get across with the book – it doesn’t really matter if you think the music was good or bad, as that’s totally subjective. It’s that if you’re interested in what happened to wider pop culture in America and the UK through the 1980s – not just music but cable news, MTV, wrestling, advertising – you can’t tell that story without looking at glam metal. You just can’t.

SG: What did you learn about the genre that you didn’t already know in the process of writing the book?

JQ: I think the size and scale of it surprised me. It did very well to cultivate an image of being this underground scene when it was actually huge. Even bands from quite a long way down the food chain were selling out arenas and having Top 10 hits. When Def Leppard released Pyromania and MTV was really getting going, they were pretty much neck-and-neck with Thriller-era Michael Jackson for popularity on the station.

SG: In terms of acceptance, do you think metal in general is given a fair crack at the whip?

JQ: Yes and no. Glam metal is still a bit like the embarrassing cousin, but I think over the last five years or so there’s been a shift about metal more widely. I think most people would accept now that Black Sabbath were a hugely important, exceptionally creative band and left behind a really significant body of work. The work somewhere like Home of Metal in Birmingham has done has really contexualised that. Things like the Metal Britannia film on BBC4 helped make that case. It’s easy to forget how much of a joke bands like Sabbath and Priest were until a few years ago (ed’s note: you could argue this right up to the Osbournes – arguably the last MTV hit in the pre-streaming).

SG: If you were trying to convince someone after the pub of the genre’s worth, what three records would you play them? (thinking specifically music rather than videos, as that obviously gives people a very different impression)

JQ: You’d have to start with Def Leppard’s Hysteria. It’s an amazing work of songwriting, but it’s essentially built like an electronic album. Mutt Lange (the producer) recorded all the individual elements of the band and then – I’m simplifying here hugely – went away for six months and built this unbelievably complex, multi-layered collection of songs which the band then had to learn to recreate live. And they did, brilliantly. But it’s an astonishing piece of work. I think the anniversary shows they did a few years ago for it led to something of a reappraisal of the record, but it’s really not appreciated, either as a piece of musical work, or just as an astonishing example of ambition fulfilled – these absolute grafters from Sheffield setting out to make heavy metal’s answer to Thriller and completely succeeding. It’s difficult to overstate its importance or how well it holds up. The songwriting is as good as ABBA, and weirdly similar in many parts.

Secondly, Appetite For Destruction. Gn’R would dispute the glam metal tag (but then so would most bands) but it’s a) a masterpiece and b) the record which ultimately broke glam metal. It’s like all the greatest bits of the previous 30 years of guitar rock compressed into one record. But it’s so malevolent, and bleak and damaged, it made everyone else sound like they were play-acting and did a lot to render the whole glam scene obsolete. Maybe the greatest debut of all time.

Finally, I’d go for Skid Row’s debut, Skid Row. It’s maybe the last really great glam metal album. Fast, melodic, dumb, adolescent, incredible playing and one of the hardest, tightest live groups I saw at their peak. You don’t hear the namechecked much these days, but in their day they were untouchable.

SG: And what is the greatest visual representation of glam metal in video form – and what’s its nadir – the glamageddon as it were?

JQ: It’d probably have to be Rock of Ages by Def Leppard. David Mallet directed, and it’s this astonishing run through every stock metal image you could hope for – cowled monks cackling, terrifying owls, a medieval looking woman lashed to a stake, a sort of primordial swamp with a moshpit emerging from it, a scene when Joe Elliot stumbles under the weight of a comically oversized broadsword before it transforms in a flash of lightning into Phil Collen’s guitar. There’s also a close-up on Phil’s little white-denim clad bumcheeks waggling around during the guitar solo. It’s pretty special.

Worst: Probably Warrant’s Cherry Pie. It’s basically what people envisage when they think of why they hate glam metal: cheap video effects, bikini models getting sprayed with fire hoses, daft practical jokes, awful camera mugging. Warrant actually did some pretty great records, but Cherry Pie was so reviled it had this massive halo effect on their entire output. They went on Channel 4’s The Word to do it and got pelted off stage with the promotional cherry pies that they’d given out to the crowd. A bloke in a cowboy hat trying to fend off a hail of smashed up pastries and fruit that he’s paying for out of his advance and a load of London trendies are chucking at him. It was the awful moment when you realised Glam Metal was doomed.

SG: Do you think the success of Appetite for Destruction destroyed the genre more than the supposed metal killer Nevermind?

JQ: Totally, and I make this point in the book. Gn’R weren’t really a punk group (although I got into The Damned via seeing Slash wearing their t-shirt), but they’re in that lineage and they’re genuinely malevolent and sleazy in a way that a lot of the other bands aren’t. They hated that whole glam scene and very early on they’re telling interviewers how they just want to destroy the whole thing. I don’t think they ended glam, but Appetite For Destruction gives it a serious slow puncture. Everyone else just looks so wholesome by comparison once that record comes out.

The link with Nirvana is interesting. I wrote a piece a few years ago for The Guardian saying how similar Axl and Kurt were in many ways. If you took the stupid, racist, offensive verses out of One In A Million by Guns n’ Roses, it sounds like something by Neil Young circa On The Beach. That acclaim that Nirvana got for Unplugged a couple of years later could have been Guns n’ Roses’ if they hadn’t shot themselves in the feet so badly. And people always speculate about what greatness Cobain might have matured into. Well, you know, he might – equally, he might have gone the Axl route of disappearing up to a mansion in the hills, working on some never-ending project, sporadically popping up to sue an ex bandmate or have a fight with Tommy Hilfiger. For all that they railed against each other at the time, I suspect they were pretty similar personalities.

SG: Has anyone carried the flame for glam metal into the 21st century or do you think its a chapter in the history books now? I started wondering whether you could argue that Trump is the first glam metal president (in the same way Clinton was said to be the first black president)?

JQ: There’s still a residual and revival scene, but it’s so anachronistic. As I said earlier, there’s a lack of irony about glam metal which kind of locks it in the past. Even older scenes which functioned on a few different levels and had more of a complicated dimension to them could still seem contemporary. A band coming out now looking and sounding like Talking Heads wouldn’t seem out of place. A band coming out looking like Cinderella would just seem like a joke. Everything has to function on two levels now, like when Alex Turner suddenly started dressing like Eddy Cochrane. You just kind of knew that it was being done as some self-referential joke, rather than it just being the way that he wanted to look. And that’s fine, but as an attitude it sort of precludes something as on-the-nose as glam coming back.

The Trump thing is interesting – I make the point in the book that Kiss probably share his world view in that as much as they’re a band, they’re a giant branding and pyramid selling exercise. And I sometimes look at Poison – basically unconvincing blonde millionaires, whipping up crowds at state farms in Missouri by singing about how they’re ordinary working joes and you think… yeah, I’ve seen where this ends

Nothin’ But A Good Time is published on September 3rd (Today!) by Unbound