Just before Christmas I leave London, where I have been sleepless for most of the month, and go back to Dublin. I’m finally observing a more normal sleep schedule. Sleep came back slowly; the heaviness, and the half-open eyes. I began to surrender, taking naps during the day, then late in the day, then easing myself into sleeping at night and waking in the morning.

The more I thought about sleep, the less I was capable of sleeping. Yet the more I read about it online, the more I felt like I wasn’t thinking about sleep enough. Modernity, it strikes me, doesn’t leave sleep to chance. Not when its alternative – the controlled, perfected sleep, a mirror of the productive work day – is so difficult to attain, and so lucrative.

The first story published by William Gibson, in 1977, is called ‘Fragments of a Hologram Rose’. In it, a man called Parker has trouble sleeping and relies on a technology – ‘ASP’, which stands for ‘apparent sensory perception’ – to lull him to sleep. It shows him footage shot from the perspective of a ‘young blonde yogi’, who does exercises on a beach in Barbados before falling asleep. The device blurs the subject’s perception with that of the viewer, inducing calm.

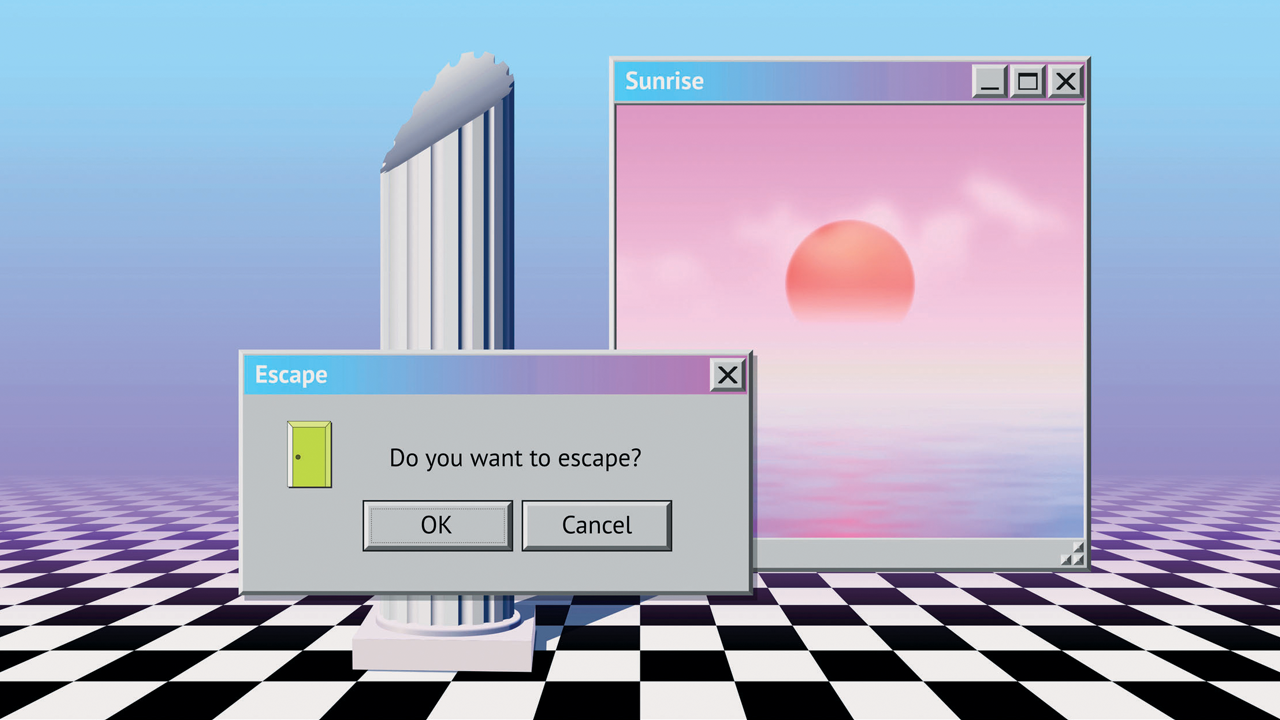

ASP could be Gibson’s premonition of VR, but it might just as easily be like ASMR, where video and audio are allowed to intensely manipulate the senses. Personal memory and film intermesh; the ASP carries Parker back to a series of scenes from his own life, where his girlfriend leaves him and takes a rickshaw into the anonymous night. Parker is world-weary, haunted and tired, and the device manipulates his emotions. We’re informed that he hasn’t been able to sleep without an ‘inducer’ for two years; he’s addicted, a cyborg whose prosthesis is sleep.

Gibson is known as the pioneer of cyberpunk – science fiction set in a dystopian future, characterised by ‘low life and high tech’. But his portrait of technology as a cure for insomnia and loneliness might not be far from our present day.

Today, for every lonely person kept awake by notifications and the endless scroll, there’s someone else sleeping with technology, pursuing an augmented, monitored sleep. Products are marketed to those seeking to achieve it, and communities have evolved around sharing experiences and experiments in sleep-hacking.

Sleep technology has progressed from science fiction to reality, and the internet is a battleground for companies seeking to turn our eight hours into profit. The most accessible, commercial face of this trend is the current market for mattress start-ups; it’s likely you’ve noticed ads for them, sponsoring podcasts, or paying to be mentioned by Instagram influencers. They’re companies based entirely online, rather than in showrooms, which deliver mattresses they claim are engineered with varying degrees of innovation for the perfect night’s sleep.

After my visit to the nap hotel I looked up Simba, the company that had provided it with mattresses, and fell down a rabbit hole reading about the ‘mattress wars’. Casper is likely the best known of these brands, with Eve, Emma and Otty, among others, biting at its heels. They’re called ‘bed in a box’ companies; once your mattress is delivered, you transport the box to your bedroom, unfurl the mattress, and it puffs up to its full, decompressed size.

These start-ups emphasise technology and innovation, framing sleep as a ritual of competitive self-betterment. In search results, Casper is ‘an obsessively engineered mattress at a shockingly fair price’. Leesa has a ‘universal adaptive feel’ and ‘combines cooling Avena foam with pressure-relieving memory foam’. Ghostbed has ‘supernatural comfort with cooling technology’, while Purple is ‘the world’s first comfort tech company backed by science’.

All of the above are excessively, exhaustively reviewed on dedicated mattress sites and in YouTube videos. The reviewers, by and large, are young, wholesome-looking men; they manage to take all implication of sex and even intimacy out of bed-reviewing. Their tone is earnest. They wear freshly laundered hoodies and occasionally mention their girlfriends and wives. They also profit from affiliate links; with each click-through from a potential customer, the blogger takes a small cut of their purchase. In videos, we watch them sleeping, or at least pretending to sleep. The internalised surveillance of social media becomes even more pronounced here; ‘sleep marketing’ falls at an intersection between consumerism, biopolitics and the quantified self.

What most of the reviewers I encountered had in common was their use of the phrase ‘the best sleep’; the sleep all their efforts are in aid of, which is achieved not through relaxation, but through consumerism and intensive self-monitoring. The reviewers wear devices to track their hours of sleep, reporting on whether the mattress was good for back pain or side-sleeping. The mystery of sleep can be harnessed and controlled. The best sleep is a consumer quest; the best sleep is something that you can buy.

That the ‘bed in a box’ companies target young people as well as older, more settled consumers is significant; it implies that young people, less likely to own property or even a car, and destined to move between a series of rented apartments, would however be willing to take a mattress with them between these moves. The rising number of divorces and the number of millennials waiting longer to get married has been kind to the mattress industry; the longer we stay alone, the more individual mattresses we’re going to need. Your mattress is real estate for life (or, rather, for five to ten years, after which you’re encouraged to replace it). It is your home within a home; your escape; your guardian angel; the expensive, foam-padded keeper of your body and soul.

Technology steps in to monitor and control sleep, even when the brain has no choice but to switch off. Once you’ve found the perfect mattress, you can enhance your sleep further with apps and wearables. Sleep tech is a popular theme on Kickstarter, where crowdfunded projects include an adjustable pillow with a corresponding phone app, a wifi-connected alarm clock which doubles as a ‘sleep revolution device’, the ‘Bedjet 3’ climate-cooling air-conditioning system for beds, a ‘Sleep Shepherd’ brainwave-monitoring nightcap and the ‘Gravity’ weighted blanket, which was advertised to me on Facebook. Meanwhile in more mainstream technology, in 2016 Apple introduced the ‘Bedtime’ feature for the iPhone, a sleep-tracking app that can be configured to send alerts reminding the user it’s time to go to bed.

I have experimented with sleep-hacking over the years, less out of curiosity than from desperation. I’ve taken a consumerist approach to sleep, seeking out pills to make it easier. I’ve fallen into online communities, reading their stories and comparing their experiences with my own. Time passes, and then my insomnia comes back. Perhaps I’m not trying hard enough; perhaps I need to lean into my own mutation.

The mattresses, the apps, the nootropic supplements – all of them promise to deliver ‘the best sleep’, the sleep our bodies long for but our minds have forgotten. It comes at a cost; in darkness, as in daylight, technology estranges us from our senses.

Nature recedes, in memory, on the screen, until it exists only in dreams.

Roisin Kiberd

‘The Disconnect’ is out now, order it from bookshop.org here