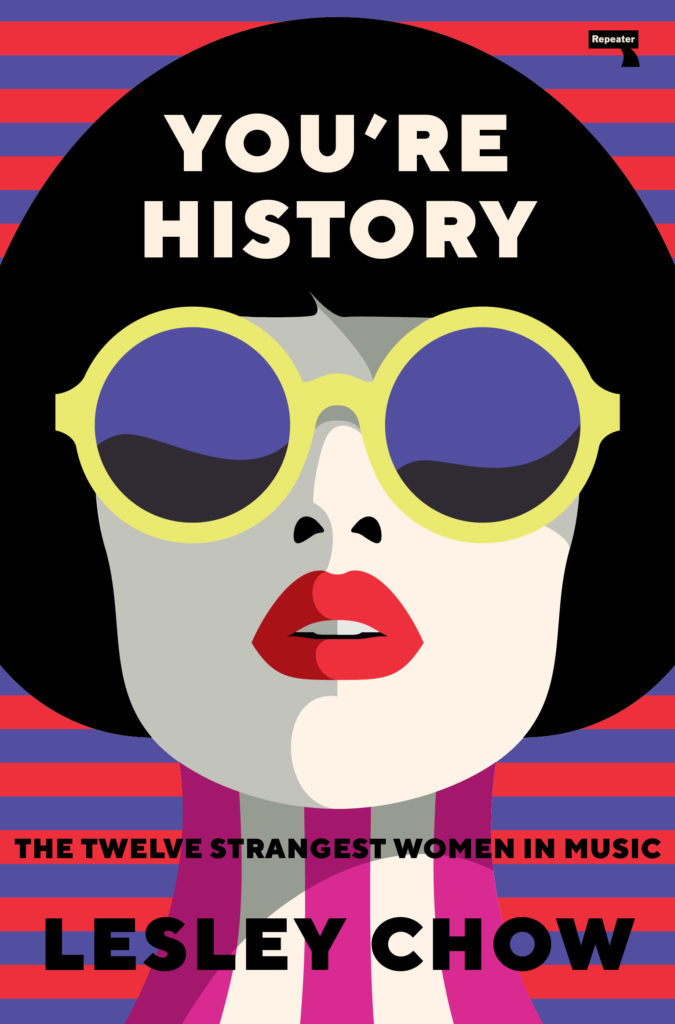

It’s our great pleasure to share with you the opening chapter of author Lesley Chow’s new collection You’re History here on The Social Gathering. It’s a great introduction to story that offers an explanation as to why Lesley chose the twelve ‘strangest women in pop’ as the basis for her book.

The artists I write on at length in the book You’re History happen to be women. A few are truly respected; a good deal more are regarded as guilty pleasures, too tuneful for acclaim. Some are considered fashion-plates or pop cultural jokes. Others, such as Chaka Khan, are seen as wonderful forces of nature with little authorial agency.

What these artists have in common is that they are all anomalies: pioneers in the making, whose output has been too strange for the culture to fully digest. While the greatness of Khan, Neneh Cherry and even TLC has been acknowledged, these women are not influential enough. One reason may be that most of them are not primarily word-based: there is verbal innovation, but it is the kind that comes across sung rather than spoken or written. A monologue is easier to dissect than a landscape of shifting voices, which explains why in-depth writing on Cherry is hard to come by.

There is a shortage of serious, long-form writing when it comes to hip-hop, R&B and pop, particularly female performers. Cherry and TLC’s Lisa Lopes mine dissonance and ugliness in the name of pop, rather than an overtly experimental genre — a risky endeavour unlikely to spawn trends. Hundreds of rock bands have appropriated the chord changes and flat affect of Joy Division, but it is harder to channel the spirit of Lopes, whose rapping combines multiple voices of indeterminate gender and source. Lopes and Cherry remain outliers, marking moments where the culture might have swerved to incorporate their influence, but somehow contrived not to.

Even Kate Bush, whose mastery is never questioned, is renowned more for her eloquence and historical narratives than the pop sensibility that makes such a striking match with her “timeless” themes. There is the assumption that musical influences are guided by taste and logic, that one has a say in the genre of one’s own genius. However, tracing influence is not just a matter of looking at immediate social background or zeitgeist. Despite the claims of traditional biography, what hooks a singer’s ear may be the addictive hard note in a newsreader’s voice, rather than the legacy of her Scandinavian or Afro-Caribbean roots. At a time when references tend to be clearly flagged and respectably eclectic, it is vital to acknowledge the imaginative leaps that an artist can make: out of time, out of milieu, out of mind.

Why are there still relatively few books about pop, compared to the canonical body of literature on rock? Do pop fans tend to work out their notions of rhythm on the dancefloor rather than the page? Is instant melodic pleasure regarded as cheap? Or is there the lingering perception that pop caters to the desires of teens, thereby exposing the author to ridicule? The critic Sheila O’Malley has pointed out that, when it comes to adolescent fans of pop, “their screams of ecstasy are ignored or mocked. But teenage fans picked out Elvis Presley, they picked out Sinatra … Maybe, instead of belittling teenage girls’ frenzies, we should follow the sound to see what the fuss is about.”

My goal in writing this book was to “follow the sound” with curiosity rather than derision: to track anything that the ear picks out as striking and memorable, regardless of reputation. It can be tricky to decipher emotions that feel private and fugitive, even though they are provoked by objects that are unquestionably commercial.

I have explored pop songs that are potent in spite of their seeming lyrical banality. This involves trying to understand the emotive effects of timbre, noticing how the meaning of words changes on contact with the bass and, most importantly, determining where the heat of a song is located. As the composer David Schiff has noted, a song can contest its lyrics and reveal itself through the “warmth of the melodic lines, and musical wisdom always trumps verbal wit.” Listening closely to pop means marvelling at how pitch, rhythm and intonation come together in a way that is precisely right yet difficult to fathom — all those little miracles that pop does so brilliantly.

In particular, I want to advocate for urgency and pleasure, so my focus is on performers whose effect on the body is hot, explosive and immediate, rather than those who adhere to typical standards of refinement and class, such as Grimes and Joanna Newsom, and who are more likely to be celebrated as a result. The artists in this book deal in moods that are generally considered undesirable: an insistent fakeness, emotional dishonesty, uncontrolled sexuality, strident superficiality. Their music tends to grate rather than soothe.

Shakespears Sister go beyond quirky and play with images of the grotesque, envisioning love as a form of witchy possession — a theme that has recently been taken up by the most unlikely of artists: Taylor Swift. Rappers Azealia Banks, Lisa Lopes and Nicki Minaj similarly work with gut levels of repulsion, testing out the power of feminine sleaze. Banks, Lopes and Minaj incur serious violations of taste, in a way that more consistently acclaimed musicians such as Janelle Monáe rarely do. They are anomalies in that their songs leave an acrid taste in your mouth — they are drawn to working with disgust and abject topics. They risk sounding shrill. All of the artists in this book are unpalatable, in one way or another. Even the loveliest voice among them, Sade, has oddities that discomfit the listener.

You’re History deals with English-language artists, most of whom have enjoyed at least a degree of chart success. In part, this is to draw attention to the fact that music can be ubiquitous yet underrated. Pop, by and large, is still seen as foolishly infectious — the cultural equivalent of junk food or fast fashion. The critical focus seems to be on removing the contagion as opposed to explaining why it catches on. Therefore, a song as strange as Rihanna’s “Umbrella” or Janet Jackson’s “Nasty” can attain universal recognition while the secrets of its power remain untapped.

The innovative film critic Judith Williamson always preferred reviewing mass-market movies to little-seen masterpieces: her theory was that she wanted to find out what it took to strike “the right chord” with the public, rather than searching for the marginal or the underground. In a similar way, this book seeks to identify the elements of a song that touch a nerve; I have only included one chapter on a singer whose work is relatively obscure, Michelle Gurevich. I look at several artists – Minaj, Rihanna, Sade – who are fascinating despite reputation. These women may be well-known but they are critically under the radar, their peculiarity masked by popular success. While Jackson and Khan are considered great performers, their songs seldom receive the close analysis they deserve, unlike the work of the introspective, indie songwriter.

A pop smash may be written off as a spark of serendipity or dumb luck, but it is a formula of pleasure that has yet to be perfected. Record companies do not have full control over what hits home and produces love. This is because memorable songs have a necessary component of strangeness that is hard to calculate. What lifts a song into greatness may be a singer’s impulse to lengthen, slur or skip over a note, or an incorrect turn of phrase that nonetheless becomes iconic. Effects like these interrupt the concept of the songwriter as a single identity and authority. It is tough, if not impossible, to consciously build such whims into a song’s structure: they are more often discovered during rehearsal, the evidence of a quirk not resisted.

I found it particularly challenging to come to terms with the complexity and contrary nature of TLC, Jackson and Banks. On their debut album Ooooooohhh… On the TLC Tip, TLC encompass an astonishing range of sounds and attitudes: their songs combine the macho posturing of punk with ‘60s girl-group sweetness. Skipping between hip-hop, R&B, pop and funk without ever settling on a genre, the record is constantly on the move, surprising us with musical twists and sudden mood changes. Bragging lyrics and harsh effects give way to moments of introspection: the women are just as fierce in describing their passions as in attacking their detractors. In contrast to most of their contemporaries, from SWV, Brownstone and Jade to Destiny’s Child, who tend to present a rational, unified front, TLC give us multiple, jostling perspectives. The songs come across as mercurial, alarming and vulnerable: a series of mixed messages designed to unsettle.

What’s amazing is that TLC did of all this in plain sight: they are America’s best-selling female group. While the band seems as determined to smash boundaries as, say, Nina Hagen, they are not obviously avant-garde: they present us with threatening voices, but do so under the guise of sassy, mainstream pop. This may be the reason why they were able to take so many niche sounds and bring them to the centre of ‘90s culture.

This book is an argument for the cheap, the shrill, the coarse, the sour, the pungent, the saccharine: for any off-putting effect as long as it is memorable. I looked for songs that have been critically discounted but continue to boggle the mind, for emotional tones that are “nasty” (in the Janet Jackson sense of the word) rather than balanced, and for the one-off hit more than the tempered masterpiece. Above all, I wanted to pay an overdue tribute to the best “oohs” in the business.

Lesley Chow

Order the book right now direct from Repeater!