HEALING STUDIO

Come for a half-price ear-clean therapy service.

Limited time only!

Or 25% off shoulder massage

Exclusive organic candle and soap sale

I’m proud of the flyers. Printed on thick, linen cardstock at the Office-Mart. There was a queue behind me, and so I’d typed them up so quickly on the self-serve machine, that I’d failed to notice I’d flattened a small fly against the screen. When I lifted my hand, it was dead under my middle finger. When you see one, you see them everywhere. Little sticky flies all over the Office-Mart.

I promised myself that I wouldn’t be passive, that I would make this business seen. I would not let it become one of those storefronts that appears for a few weeks before slinking away into a vacuum, a blackhole. A new brand occupying its spot, transforming the habitat of what had once been somebody else’s aspiration.

This thought has been reoccurring as a sort of anxiety recently, materialising once again as I drive past the valet, up the ramp to the rooftop staff parking lot. Vic is saying something about the shrinkage of body size in fish as heating continues in the ocean. After three attempts to park, I unclick the belt and break my nail.

‘Oh well,’ Vic sighs, staring straight ahead. Then, ‘I could get used to being driven here every day.’ I show my nail to him and he says, ‘Oh shit.’

We walk towards the automatic doors. I make a mental note that we’re on level 3E, where staff are to park. Usually I park in 1C as a casual shopper. It allows immediate access to the supermarket on the lower level and is in close range to the phone-repair store.

Near the bins at the entrance, two pharmacy sales assistants who Vic knows are kicking a hacky sack between them. They nod at Vic without saying anything, their focus intently on the sack. As Vic approaches, the one with a beanie says, ‘Hey, man, how do you make that grapefruit soap your girlfriend made? It’s really nice. But my girl’s allergic to olive oil. She got an itch last night between her legs.’

Vic says, ‘Animal fats, lye flakes – that’s the sodium hydroxide part of it – distilled water, sugar and salt, lavender oil, synthetic colourant, the mixture of a sodium paste, and grapefruit-scented serum. No olive oil.’

Vic has an impeccable memory. When he talks of substances, it’s as if they are visually synthesising before him, the logical, chronological equation for each compound he describes.

•

Vic unlocks the plastic screens at the pharmacy. He switches the lights on and pulls the racks of sale bins to the front. At the back, behind the pharmaceutical desk, he puts his white coat on, loops his lanyard over which reads ‘Victor’ and ‘Store Manager’, then ties his hair back. The Vietnamese couple who own the pharmacy seem to urge only him to wear a net. Because of its texture, they had said. So he sometimes wears it and sometimes doesn’t, depending on how he’s feeling.

He goes to the back to get me nail clippers and I sit on the bench, poking my thumb with the sharp of the leftover nail, the vulnerability of it left half standing. Bending like a visor. I go to spray a Marc Jacobs on myself and regret it because I see that there is a YSL sitting out too. It is embarrassing to want to smell of something.

Vic appears again, sniffing the air. ‘You’re ridiculous.’ He passes me the clippers and wraps a hairnet over his head. We personify the scent. A feminine or a masculine thriving on interior paradises, who decorates with house plants but not so much that it seems like they do hot yoga, because they just do the regular yoga, even so casually as to be guided by a YouTube yogi. A feminine or masculine who goes to a car wash service and doesn’t clear the belongings in their car because they’ve got two of everything. A feminine or masculine who brings a two-litre water bottle with them on a visit to the bank. A feminine or masculine who cooks without an apron, but with their hair up and hotel slippers on.

Vic goes to inspect each aisle. He looks carefully at the products, referring back to his pad of notepaper. I watch from the bench, flattening my hand over the flyers.

The silence before the music is turned on throughout the complex is ethereal, feels almost as if we’re in a spaceship and the processing of time has shifted.

It was this strange comfort in the design of a shopping complex that prompted me to convince my father that Topic Heights was the right place for my business. In every city we had moved to for my father’s contracting business, it was the natural ecosystem, separated by climate and light, which would differ immensely. Think the difference between Malaysia and London. But in a shopping complex, the climate and light remain the same. It is the landscape of familiar logos, the behaviours of shop assistants. It is the indoor planting, the skylights, all designed to replicate what the land had once been before it was bulldozed. The climate is regulated to suit the likes of the common shopper. For someone who has come from a different one. And though I know this, I had grown up searching for a sameness, as most children do. It is a guilty pleasure to want so badly to be encased in it.

I go and look through the snacks shelved at the front desk. I take a pack of jellybeans and open it, ask Vic to come over and guess the flavour. He covers his eyes with his hand and opens his mouth a little. He guesses liquorice. I tell him that was an obvious one.

He says, ‘You know, liquorice is associated with cold and flu syrup because the plant they use for it is the exact same. Its flavour is so pungent that it masks the original medicinal taste.’

He guesses orange for the next one, though it’s strawberry. I tell him he’s right anyway to see if he’ll notice.

In a bit, the other employees arrive and report to Vic, who notes this on the timesheet. At nine, the presence of the first customer modifies the atmosphere, noticeable in the way Vic’s face and the manner of his gait change. I hop off the bench and go to sit on one of the fold-up stools in the back. My phone is in my lap, in progress of playing an analysis video about the movie adaptation of No Country for Old Men. I notice someone in the sectioned-off shelf area that meets the storeroom, eating out of a tin obnoxiously. Scraping the fork around inside. He works at the prescription desk too, I suppose.

He looks up at me, catches some beans back in his mouth and says, ‘Hey, hey, do you even work here?’

He looks as though he’s carried over the vigour of his eating into the act of intimidating me. I feel the weight of my jacket around me. Hold it into myself.

‘Well?’

He looks a bit older than me and Vic, though I cannot tell for certain. He’s a skinny Caucasian guy with minimal toddler hair. Wearing a short-sleeved shirt and a bland tie. Some tattoos showing, one of a beckoning cat. Chains on his teeth, I notice when he opens his mouth to speak.

‘No,’ I say. ‘But I’m opening an ear-cleaning studio on the next level.’

He points his fork at me, nodding. ‘You know, you’ve got to be careful in the health and self-care industry. It isn’t about skill or product as much as it is about socialisation …’ – he scoops more food into his mouth – ‘and charisma.’

His teeth look as though they’re squirming between his lips when he smiles. As if for attention. He chucks the bean tin into the black bin beside the cabinet storing asthma inhalers. He turns back around on his heel with a swivel. I cannot really tell how old this guy is. His mannerisms don’t seem to match his body. The mannerisms look as though they’ve occupied space longer than his body has.

The analysis video is talking about how Chigurh often checks his boots for blood.

He sees me watching my phone, continues to talk. ‘It’s easy to move up the scale, you just gotta watch your every word. One minute you’re hired. If you’re sweet-talking them, complimenting their hair. The next minute you go on and imply they’re gaining weight or not pulling any weight and you know, you’ve got yourself fired. Put on small-talk lists between their friends and colleagues,’ he says. ‘Entertainment for the dogs.’

‘I run my own studio so I don’t really need to worry about that.’

‘I mean, your customers. Your customers hire you, never forget that.’

The video is talking about how there is no musical score.

His eyes are wide with a sort of expecting.

I pause the video.

He unfolds his arms, reaches out, shakes my hand with his bony one. He’s wearing a silver Rolex, which slides a little down his wrist according to such drastic movement.

‘I’m Jean Paul.’

‘Like Sartre?’

‘You saying that right? You tryna say Sartre? You know who that is, right?’

I decide he must be at least thirty-three. There is too much practice in the way he reacts. He could be offensive, but somehow is not. He could be brash, yet there is something endearingly vulnerable about him.

‘I could be the manager here and I’d have every right to ban you from the store for being back here,’ says Jean Paul. He laughs disgustingly. ‘But even if I were, I wouldn’t.’ A comfortable, silent moment. He goes to look at my flyers lying on the bench beside me, thumbing his chin. ‘You want me to hand these out to customers today? I could.’

‘Sure. Yeah, that’d be great.’

He is the kind of person you cannot for the life of you tell the age of, due to the way their soul moves around in their hand gestures, the way their shoulders are held comfortably around their neutral chest. Could be twenty-six, could be forty-five. Regardless, his body looks as though it’s been in routine and is attempting to crawl out of itself.

He pulls a pharmacy coat on and I remember a time Vic complained about being brutally scolded by the owners for wearing a tie. As store manager, Vic seemingly holds a lot of the control here, in charge of everyone else’s demeanour, but Jean Paul is wiping his lip and tucking his tie back in between the buttons of his pharmacy coat without blinking.

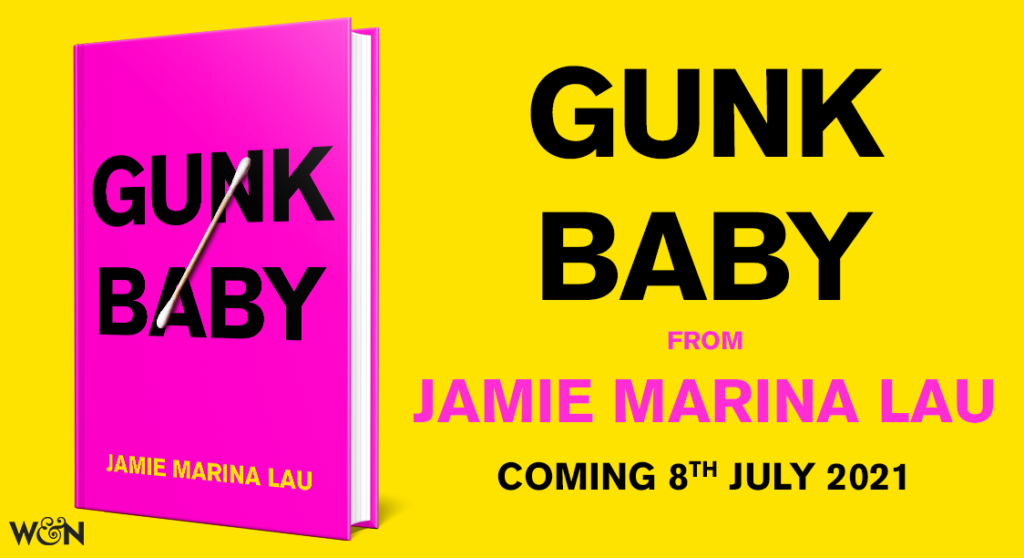

Jamie Marina Lau