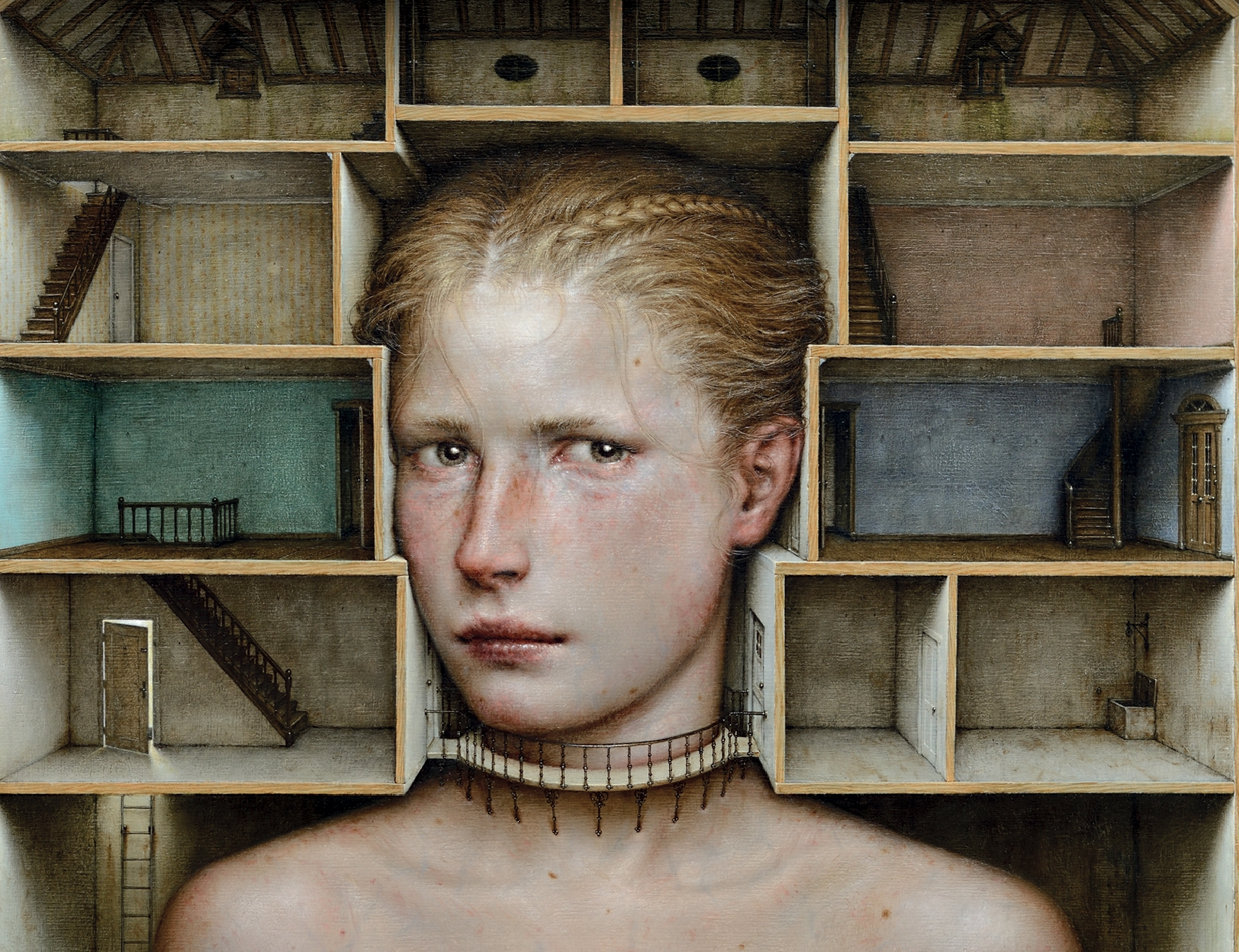

I lived in an ancient tenement building decades ago, that was so creepy and weird I knew it would one day form the basis of a novel. It takes a long time before we are ready to write certain books and others will always be a small act of madness at any time, Luckenbooth was one of those for me. I set out to write a novel about Edinburgh set over nine decades in which a single character ties all the others together in some way. The devil’s daughter Jessie MacRae arrives in 1910 to begin her life working for the Minister of Culture, she is to bear him and his fiancee a child. A hideous event occurs and Jessie curses the building and its residents for one hundred years. As you move up through every decade the curse manifests in one way or another. I had to research nine decades of history, fashion, political or social change. It was an act of architectural and conceptual non-knowing, entering the building myself not sure exactly where I was going to end up or what would occur along the way. I knew in this one that I would be working toward an ending that starts at the beginning though. The novel would not be a form of Penrose stairs, each decade would hold it’s own clarity and identity and theme. Love, revenge, the occult, abandonment, loss, there is a bone mermaid and a 650 pound polar bear called Baska who marched up Leith walk in 1919. The world of Luckenbooth is still very alive in this city. You can visit her pubs, walk by the places that her characters live. It was a love letter to my city. Someone said to me today that it is so dark that many would think it a funny kind of love letter. It’s a city of dark and light where the past walks alongside the present and most of its best stories go untold, those are the ones I look for. If we weren’t in lockdown now I’d be tempted to leave altogether. I’ve had my say.

Jenni Fagan

1910

Flat 1F1

Jessie MacRae (21)

the arrival

My father’s corpse stares out across the North Atlantic swells. Grey eyes. Eyelashes adorned with beads of rain. Tiny orbs to reflect our entire world. Primrose and squill dance at his feet. His body is rammed into a crevice. The shore is scattered with storm debris. Cargo boxes. Little green bottles with faded labels. Swollen pods of seaweed slip underfoot. It takes me an hour to get from our clifftop to the water’s edge. I have a blue glass bottle. It is tincture of iodine. Skull and crossbones on the front. I wash it out. Tell it my secrets. Stopper them. Lay it on the water. When I look back our beach has a long straight line– right down the middle– like the spine of a book.

It is where I dragged my coffin.

I use his oars.

Push the vessel he built for me– into waves. It is not the journey he foresaw me taking in it. My father built one for each of us from old church pews. Knocked them together outside the kitchen window, so my mother would see. She saw the world through those four square panes. Each season. Each sorrow. That night he made her sleep in hers. Then my brother took to his. I varnished mine ten times without any premonition. How buoyant such a thing can be! A light spray fans peaks of waves. I will not look back at him in his crevice. It had to be done like this! Hoick my skirt up. Wade into the sea. Pale bare thighs bloom red in the cold water. I kiss my mother’s cross. Set it onto the floor so there’s one holy thing between me and oblivion. The sea won’t take me. I am the devil’s daughter. Nobody wants responsibility for my immortal soul. My address cannot be– The Devil’s Daughter, North Sea. I’ll never knock at heaven’s door. Hell knows I could do far worse than take over. I dip the oars in. Pull away from the island. I watch the dark blue line of the horizon. A seal pops up. Black eyes. Long whiskers. He’d have me sire a seal child if I’d do him the favour of drowning.

On the first night I lay down in my coffin when the winds drop.

Easiest sleep of my life.

When I wake the ocean swells roll bigger and bigger. I sing. Smoke. Thin spires rise up. I breakfast on oatcakes and cheese. Run chapped fingers through the water. The seal brushes them with his whiskers. I eat a raw fish I brought with me. Lob the bones out. It barely touches my hunger. A hairline crack appears in my coffin. Cross myself three times. Wish I had brought more to eat. I see no ships all day. The sun falls with regularity. Her opposition – the moon– rises. It is round and yellow – a single eye to watch my journey.

On the third morning a fog unfurls.

A ship calls out long and low.

The spirits of the sea are matched in sorrow by the living. I rest my elbows on the sides. Scan the horizon. All I can see is a grey abyss that feels like it has come directly out of me. The day passes in misery. At night the skies clear and wind picks up faster and faster until sailing feels like flying. Arms out – travelling through a hundred, million, billion– stars.

I have no compass.

When I draw near land I shout – where are we?

Those who don’t faint, or cross themselves, or throw something at me – give enough information to get me to my destination. I drift into the Water of Leith at dawn. Four cormorants skim across still water – wings almost touch their own reflection. So graceful! Stash the coffin behind the trawler boats away in a corner of the docks. I tie it up. Leave it bobbing in the harbour. I climb out on rusty wall prongs. Men argue nearby. I strip quickly behind barrels – comb my hair twenty times, tighten my corset, pull on clean stockings, slip my ma’s best dress over my head. It is charcoal with a square neck. Low enough to see a heart beat. Tie up long brown hair. My skin is white- blue. My lips are keptfresh with Vaseline. There are neat green buttons on my leather boots. The priest bought them for my mother. She gave them to me. I throw my farm boots over some barrels. Somebody will use them no doubt. My old dress is stuffed in a bag. I pull out the last piece and carefully fix the clasp – her silver cameo.

I’m ready.

Walk quickly along Constitution Street.

The thing is to try and look like a woman.

Not a demon.

I have the eyes of every man on me.

Flawed thing.

All want.

They could find so many reasons to hang me.

Jenni Fagan

Luckenbooth is out today – pick up a copy here