Long before Christan Marclay was proverbially dragging in people who don’t normally go to art galleries to see his conceptual masterwork, The Clock, he was creating musical mélanges with turntables in homage to some of the greats. Turntablism began in the 1970s, with early practitioners like DJ Kool Herc, then became a central tenet of hip-hop in the 1980s; Marclay was recording without grooves, melding records together for a more dreamlike and abstract effect from 1979 onwards. He recorded some of these avant-garde experiments externally as he performed them live. In 1988, he made More Encores with tributes to Johann Strauss, Frederic Chopin, Jimi Hendrix, John Zorn, and Jane Birkin and Serge Gainsbourg. A note came with the album, to give the listener a tiny insight into his intentions:

Each piece is composed entirely of records by the artist after whom it is titled. ‘John Cage’ is a recording of a collage made by cutting slices from several records and gluing them back into a single disc. In all the other pieces the records were mixed and manipulated on multiple turntables and recorded analog with the use of overdubbing. A hand-crank gramophone was used in ‘Louis Armstrong’.

Naturally, the track ‘Jane Birkin And Serge Gainsbourg’ features a sample of ‘Je t’aime … moi non plus’, but there are other records that would have been more difficult to get your hands on outside of France in 1988: ‘Panpan cucul’, ‘Ce mortel ennui’, ‘Pauvre Lola’, ‘Du jazz dans le ravin’, and Birkin’s ‘Di Doo Dah’, ‘Yesterday Yes A Day’, and ‘L’Aquoiboniste’.

Jonny Trunk, a dedicated film music DJ, broadcaster, and owner of arcanum label Trunk Records, says he was on the floor in record shops in the late 80s, scouring for ‘esoteric, odd stuff … TV music and what people would call easy listening’ while others chose from the racks above. To Trunk and his coterie, ‘Gainsbourg was a god … we all knew about him and we were hanging about at the Winchester Film Fair, which was on every three months, and Storey’s Gate opposite Westminster Abbey, where there were loads of old codgers with Judy Garland pictures. And we were looking for anything interesting that came from the world of TV from the 60s and 70s, and Gainsbourg was a part of that as well.’ Jonny picked up a copy of Histoire de Melody Nelson in 1990, after someone who worked at 58 Dean Street Records tipped him off that there would be Gainsbourg stock coming in that week.

‘Three records arrived, and I’d already got two of them, but then there was this blue Melody Nelson album, so I bought it and took it home. And it’s one of those records you put on and go, This is nuts. In a good way.’ Trunk became one of the first people in Britain to write about Melody Nelson, in a column for Record Collector, as it had received little to no coverage on its release in 1971. ‘I’m a big collector of sex and vinyl—not pornographic necessarily, but covering everything from the soundtrack to Deep Throat to Japanese pinky albums—and I thought that fitted in well, because he had that history with “Strip-Tease” and “Pauvre Lola” and all these sexy records. I remember in the 90s when I’d play it at dinner parties, which sounds much more fun than it was … basically you’d have four people around and you’d put it on in the background, and someone would say, What the fuck is this? It’s amazing. And I’d go, Yeah, it is, isn’t it?’

In 1991, an obscure Gainsbourg sample from his early jazz period turned up courtesy of alternative hip-hop legends De La Soul, who borrowed a trumpet top line from ‘Les oubliettes’ on their album De La Soul Is Not Dead. Simon Reynolds from Melody Maker asked about the recherché lifts, which included Gainsbourg, Frankie Valli, Wayne Fontana, and The Doors. Kelvin Mercer, aka Posdnuos, replied, ‘That delayed the album because a lot of what we sample was so old that it was hard to track down who owned the track, or whether they was even alive! A couple of the people we dealt with were sort of at the senile stage. They didn’t even know what rap was!’ In Gainsbourg’s case, that would have been flagrantly untrue, given that he’d experimented with rap himself only a few years earlier.

Writing about the retrospective impact of Gainsbourg years later, UK- based French music journalist Pierre Perrone, sadly no longer with us, wrote in the Independent, ‘Having dismissed Gainsbourg as the roué who led Jane Birkin astray with the suggestive chart-topper “Je t’aime … moi non plus” in 1969, the Brits developed a fascination for the enfant terrible of French pop after his death in 1991.’ And, true enough, references to Gainsbourg started creeping into the music press in the early 90s, usually in articles featuring Jarvis Cocker or about his band, Pulp.

‘Will the British never understand that by coming to terms with our seedy underside we may become humane individuals?’ asked Pete Paphides in Melody Maker in 1993, as he witnessed Pulp confound an audience who’d paid their money to see Saint Etienne. ‘Jarvis—Serge Gainsbourg in the body of Mr. Bean—should move to France immediately, with its risible military history, philosophers who claimed that the human soul was a pea-shaped tissue behind the nose (Descartes) and melancholy musical sleazes like Chopin and Gainsbourg. As tonight’s baffled audience testifies, the British are just too damn repressed to deserve him.’

The following year, the Maker’s Chris Roberts mentioned this kinship with the French to Cocker himself, who had also been labelled ‘quintessentially English’ by some sections of the press. ‘So I’m quintessentially French,’ mused Jarvis. ‘That’s it, I’m a social chameleon. When we go to Germany I’ll be quintessentially Kraut. Well, from what I know of the French music I like, it tends to deal with quite adult subject matter. Like, Serge Gainsbourg talking about having it off with his thirteen-year-old daughter is probably going a bit far, but there does seem to be a French disposition to lyrics which probe a bit.’

In 1994, the famous Michel Colombier-initiated repetitive loop heard throughout ‘Bonnie & Clyde’ formed the basis for two hit singles on either side of La Manche: ‘Nouveau Western’ by MC Solaar, and a self-titled track by Renegade Soundwave. The following year Serge was being sampled by alternative indie dance artists on the peripheries of the mainstream: Massive Attack took a bass line from ‘Melody’ for ‘Karmacoma’, while Black Grape made use of ‘Initials B.B.’ on ‘A Big Day In The North’.

Paul Gorman managed to secure a small piece about Serge in Mojo in 1996—quite a feat in those days, according to the writer. ‘Barney Hoskyns was the editor, he’d heard of him; you know, Barney is knowledgeable, but I couldn’t get anything out of Serge’s label in this country,’ says Gorman. ‘There wasn’t anything reissued. I had to go to the ethnic or foreign-language sections in Piccadilly to buy up French releases. There was nothing released here. And I think I got a page.’

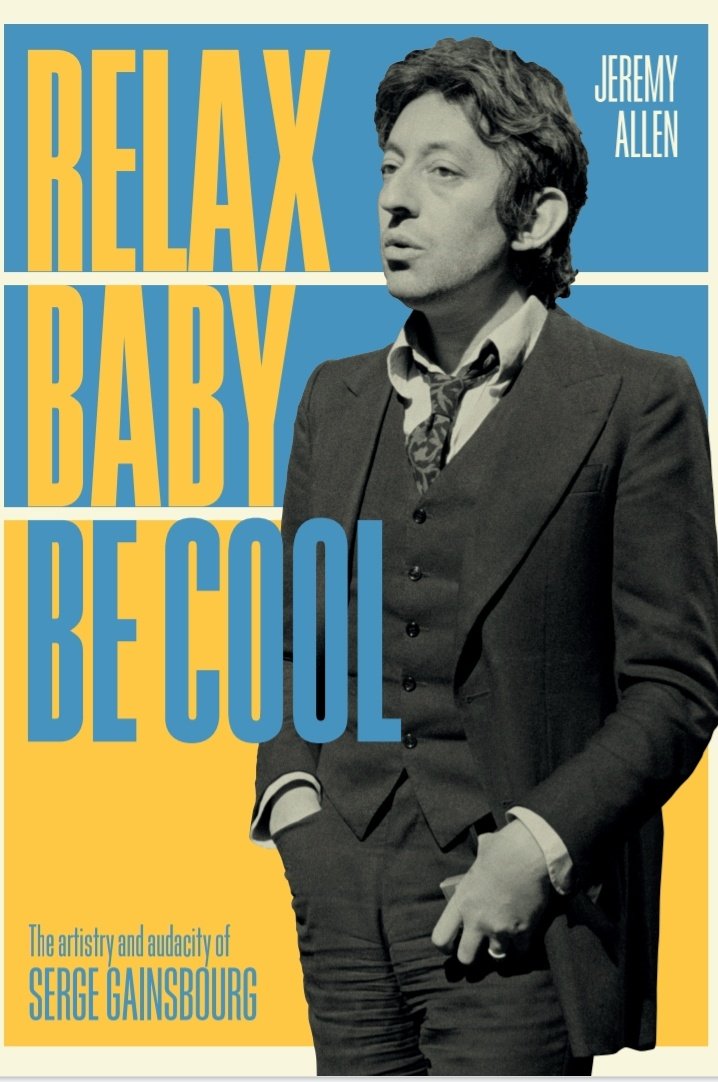

Jeremy Allen

Pre-order ‘Relax Baby Be Cool, The Artistry And Audacity Of Serge Gainsbourg’ now!