There was a certain man I used to see almost every weekday night in the pub. This man was a builder and worked for another man here in the village, and at the weekends he would travel back to the Kent coast where he ‘lived properly’, as he called it, with his wife. One night, a couple of years ago, he just skipped out. He packed his tools and the rest of his stuff into his van and left the village, owing three months’ rent on the little room he stayed in during the week. I don’t know why he comes to mind so often but it is a fact that he does. Perhaps it is something to do with the force that absence exerts on the imagination, perhaps something to do with the nature of his secretive midnight flight, perhaps it is the resonance so many of his barroom conversations seem to have these days.

He was an intelligent man after his fashion. He drank strong European lager. He knew all about warplanes and the country’s combat history, and he had some vaguely militaristic aspect – born and bred on the south coast, a navy town somewhere, and he loved to talk with the RAF officers from the local base that sometimes came into the pub. I can recall one of his stock phrases, used against anyone he had a particular distaste for – left-wingers, pacifists, climate change protestors, republicans, gypsies, overly-liberal teachers – that there were certain people who ‘just hated this country’. I heard him say it countless times. I never asked him what exactly he might mean. I stayed silent and listened to him as he talked to whoever was at the bar with him.

Outside my front door, pubs notwithstanding, the life of middle England ploughs on. It is an England of St George’s flags on the high street flagpoles, curry houses and fish and chip shops. Is that the hint of a smile across the face of the dead cod and pollock in their industrial freezers? Happily awaiting the grease paper now they know their place, their waters, are secure? So we have been told. It is an England of hollow gestures, of commemorative plates, enthusiastically purchased and destined for the charity shops that make up half the high street. An England of golf-playing accountants banging saucepans on their front doorsteps to honour whatever cause they have been spoon-fed that week, who only days before might have been overheard advising how to avoid paying tax that could have contributed in some alternative way to the applause.

Passing conversation on the high street reveals, rather surprisingly to me it must be said, an England whose government has, to use its own phrase, been seen by most to have ‘done all it can’; a cabinet seemingly beyond reproach, ‘given the circumstances’. And why would these people not feel that way when their national broadcaster, along with every newspaper and TV outlet going, expends as much, if not more, energy asking probing, rather angry, questions of the opposition as it does forming cogent arguments to put to a flagrantly corrupt and nepotistic front bench? Why bring up, for instance, the fact that a firm set up to administer the housing of asylum seekers in military barracks is apparently set to earn £1 billion from the contract? Or that the private companies running the testing and tracing services required to try and halt the spread of a deadly disease currently spend £2.75 million per day on consultants – consultants kept on, it seems, regardless of any meaningful sign of success? Or, and more importantly perhaps, why mention the added squalor that all these tenders and contracts and companies and consultancies and jobs lead inevitably, through friendships, marriages, partners, old school chums, back to the top, or more accurately the bottom, of the cesspool of power? Through all this, I am constantly reminded of that favourite phrase of the builder from the pub, and that there is the implication, then, that all this – this ecosystem made up of those people who categorically are not those ever accused of ‘hating’ the country – must then possess the quality of love. This degradation and ineptitude, the horror and lack of humility, the endless and outright lies: this is, we must believe, how one truly loves one’s country.

Online, the situation appears even more surreal. The actions of a well-meaning war veteran are turned into an endless scrolling timeline of memes and merchandise and back-dated photo opportunities for long-forgotten celebrities while the government dresses up a multi-million pound voluntary donation to the country’s coffers as a success story of their own making. Where would we go for critical thought about what the word ‘charity’ might, or should, mean in the world’s fifth-largest economy? There is more than a whiff here of Orwell’s ‘competitive prestige’ theory of nationalism. Who can clap the loudest, who can wear the most knock-off Captain Tom clothing, who can express the ‘inspiration’ they have taken the most vociferously, while simultaneously revealing nothing of the sort? Meanwhile an innocuous announcement about the stock exchange and a single shareholder of an international (is that quite right? Supra-national? Anti-national?) tech company makes himself $13 billion in a day. The idea of ‘charity’ in a world where one individual can own that kind of wealth is inherently illogical, a farce in fact, and betrays the true depths of our current depravity.

The apparent success of the country’s vaccine programme is presented as more evidence of ‘our’ supremacy, shots across the bow of a freshly-vanquished EU, the plucky little bulldog back at the top where he (and the country in its current state is surely, conceptually, a ‘he’ – tragic, deluded, impotent and angry), belongs. This victory is one for the market though, not for the military strategist or the rhetorician. Mobilising funds to buy more medicine than anybody else: isolationism, small-mindedness, parochialism, protectionism. And somebody, somewhere, on the make. Here we go again.

It feels not so much a collective mania, as a wilful ignorance of things as they are. Another of Orwell’s phrases comes to mind – ‘indifference to reality’. Nationalists, he said, refuse to see resemblances between similar occurrences in their beloved ‘nation’ and elsewhere. I think of this when I read that the British Medical Journal has described the pandemic as ‘unleashing state corruption on a grand scale’ and that our political and industrial class have used the suffering and deaths of hundreds of thousands of their own citizens for ‘opportunistic embezzlement’ of just the kind I’ve heard derided and tutted over and lambasted a thousand times in the pub when people talk about China, or North Korea, or Russia. And I think of it too, reading about a leaked report from the Labour Party suggesting they need to move towards a more patriotic ‘body language’. Use of the flag, the assertion of nationhood. More rhetoric, empty of serious thought, empty of true meaning, empty of intellectual aspiration or daring. And more of what’s already offered elsewhere. More of what’s good for you. More of the same thin old soup.

I watch a news story about a chunk of the white cliffs of Dover falling into the sea and I think of the builder and how he lives now, down there on the coast somewhere. I make a joke to a friend about the England cricket team’s chances in their upcoming series against India. It’s all too obvious, too on-the-nose. Right in the place that serves as poetic engine for all our imperial myths, all our imagined historic glory, we lose at our colonial national game. The news comes over the World Service just as the cliffs crumble and our nasty, spiteful little land sinks into the channel that these frauds and crooks have done such damage to ‘protect’.

Good riddance to us I say. Auf Weidersehen. Adieu.

Will Burns

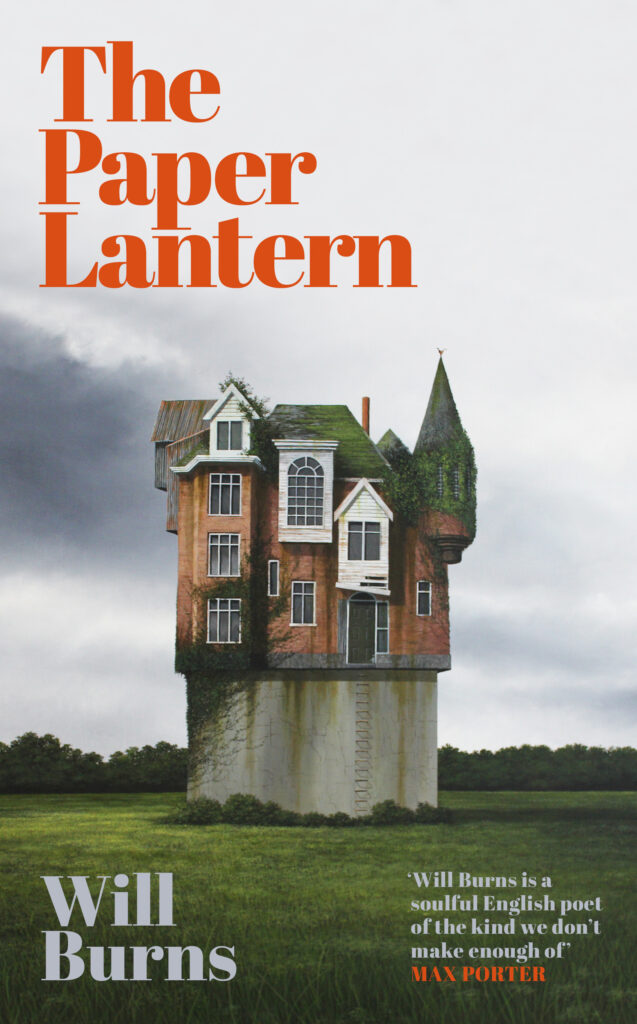

Preorder Will’s debut novel The Paper Lantern now