A Conversation About Bagpipes and Improvisations with Jennifer Lucy Allan

Last year Richard Youngs popped up in my inbox asking if anyone I knew would be interested in releasing a record he’d made with a piper called Donald WG Lindsay. I had just presented a bagpipe special on Late Junction, and so I probably seemed like the right person to ask. Bagpipes get a bad rap, in my opinion, and I’d been trying to point to some of the more miraculous or powerful properties of its sound. I was curious about what Richard would sound like with a piper, so I asked to hear it. One minute of its soft and slumberous music I knew I couldn’t pass it up. The record, out now, is called History Of Sleep, and the decorous tones of Richard’s Rickenbacker alongside Donald’s pipe drones are as is from a mist; formed on a threshold to another state, another place, another time.

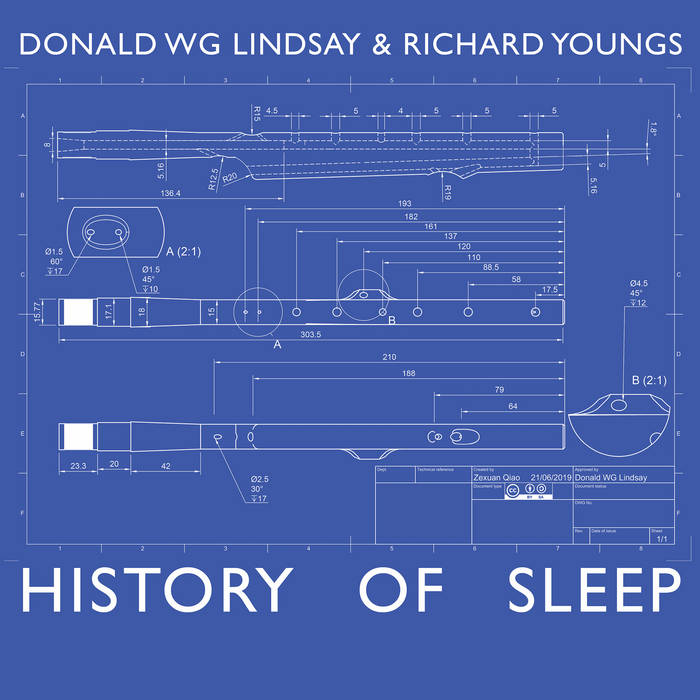

Donald is a piper and an inventor – he 3D prints his own bagpipes to his own designs, so he can reach higher and lower than a standard set, among other things. Richard is a stalwart of the British underground, he plays guitar, the shakuhachi, sings, records songs and other experiments. He’s released over 140 records by his reckoning (although that number is likely to be out of date by the time this piece is published).

I’ve been running a very occasional record label called Good Energy with Kevin McCarvel, a friend in Glasgow who also runs a CD-R and cassette label called Nyali, of raw guitar sounds and experimental music. Releasing History of Sleep on Good Energy was a total no brainer. Pretty soon after we agreed to release the album, Donald left Glasgow and moved to Ascension Island, where his wife Hannah had taken her dream job. Ascension is in the South Atlantic, 1000 miles off Africa and 1400m off Brazil.

So Kev and I had an album to release, of improvised bagpipe and guitar by a musician in Glasgow who sometimes played guitar with his feet, and a musician who 3D prints his own custom designed bagpipes and was living on Ascension Island. This bizarre collection of biographical facts for music that pulled on the esoteric, the traditional and the underground couldn’t have been more our guava jam (an Ascension Island speciality).

History Of Sleep has threads linking back to conversations about piping traditions that are hundreds of years old; notions of the proper way to play an instrument, and why – for instance – there are no bagpipes in the Fens.

So we assembled on a wobbly Zoom call, reaching over the ocean to Donald in short sleeves, sitting at one of the island’s few pubs, the Two Boats Club, where we could see palm trees in the background, hear the trade winds blowing off the Atlantic, mynah birds squawking, and dogs barking. Richard was eating pancakes in his Glasgow tenement flat.

Jennifer Lucy Allan: I’m going to admit that despite me and Kev releasing this record, I realised I have no idea how you came to play together.

Richard Youngs: I was making some recordings for a label called Fourth Dimension a few years ago. I’m a fan of pibroch – a type pf piping – and although I have no particular understanding of it, I had it in mind to do a pibroch record – it was very loose idea, fairly tenuous. I had it in mind that one half would be solo and the other half would be collaborations. And so I asked people like Alastair Galbraith, Oren Ambarchi, Neil Campbell, my godson who plays the cello, Norifumi Shimogawa, Sybren Renema, and Simon Wickham Smith to collaborate. I asked [the folk musician] Alasdair Roberts, and he suggested his piping friend Donald. So the three of us met and recorded Donald playing his pipes, and then me and Alasdair went away and messed with the recordings. The release that came out was This Is Not A Lament.

Myself and Alasdair actually pretty much butchered what Donald had done in that first session. My memory of the sound was that it was like those plastic pipes you whirl around your head. They produce this sort of high windy sound. After that, Donald said we should play together, so we met in the Piping Centre in Glasgow without a clue as to where it was going to go. I brought along my electric guitar and Ebow, and we spent an afternoon playing together. It was really good, so we kept meeting and at some point we thought we should maybe play live, and get a recording, because it seemed worth documenting. We did a performance at the Glad Cafe, one at the Tchai-Ovna tearoom, and then we booked a morning at Green Door Studios in Glasgow.

Donald WG Lindsay: Richard’s premise was a pibroch record, so I just kind of improvised with a collage of patterns that evoke or are typical of pibroch – although knowing that Richard wanted to take the scissors to it afterwards I recall repeating favourite ideas over and over, something I guess we’re both into doing anyway.

JLA: What defines a pibroch?

DL: Pibroch is the music the Piob Mor – “big pipes” – were designed to play, and it’s absolutely not what most people imagine when they think of bagpipes. Say you’ve only heard the pipes played on London Bridge or on the Royal Mile – maybe “Amazing Grace” or “Highland Cathedral” – both of those tunes are recent arrivals. All of that is what pipers call “ceol beag”, which is Gaelic for “little music”. You’d be extremely unlikely to hear a pibroch in the street at all. The word pibroch just means “piping” in Gaelic, and pipers also call it “ceol mor” – “big music”. Pibroch are long-form compositions, with a character that unfamiliar listeners might characterise as “experimental”. For any readers interested in checking it out, I’d highly recommend the album “Dastirum” by Allan MacDonald, who’s a bit of a law unto himself, and a highly expressive musician interested in the links between piobaireachd and Gaelic song.

I’m not actually deeply into it as a player – I’m a small Piper, a bellows piper, that implies more of a kind of focus on folk music, but I do play one or two pibroch that I’ve been taught properly, and I do listen to a lot of pibroch. So when Richard asked me to do this, I thought I’d give it a lash, I knew Richard’s music and I thought, let’s freestyle this – I’m into improvising on the pipes.

We ended up playing together in the in the piping centre, down in the bowels of the basement of the building there and what I brought along was just the acoustic and my own design – the Lindsay system small pipes. They’re 3D printed small pipes I designed myself, which have become an object of fascination – and debate – with pipers, because it extends the range from nine notes to three octaves. I don’t think we’ve had a bagpipe before that plays three octaves. It’s based on the Scottish small pipe, which are blown with a bellows – not your own breath like Highland bagpipes – they’re low pitched, mellow sounding, only about as loud as an acoustic guitar I guess…

Kevin McCarvel: Was Donald the first piper you’d ever played with?

RY: Yes – I don’t know any other Pipers!

KM: You don’t come across them that often. At home on Lewis I’d just known a handful at school.

JLA: For me, coming from the North West, the idea that your school instrument would be a set of bagpipes seems firstly like a cruelty to parents, but also dreamy and absurd.

KM: Donald, what brought you to the pipes? My experience growing up on the Western Isles is that it’s a family thing.

DL: My dad played pipes. I grew up in Orkney for a couple of years, but mostly in Glasgow. My brother’s a fiddler, my grandpa was a fiddler, and my uncle and one of my cousins are accordion players. So there’s a fair bit of music in the family and my dad played pipes to a certain extent, but my taking up with the pipes was more a response to hearing them. I was just blown away. I heard Duncan Mackinnon in Killin, playing reels on a hot summer day – I’ll never forget it, it was incredible. So I went to the pipes, and found myself a tutor down in Stirling. I started in my late teens, which is a late start, but the tutor said to me: you’ll have a hard time because you’re older than some of the boys I’m teaching. But the flip side is that you know you want it. I was absolutely immersed in the pipes from that point.

JLA: Does that mean it’s not too late for me?!

DL: No, give it a go. Whatever it was I’d heard in the Highland pipes was for me re-doubled in the small pipes. Pipers often treat small pipes like a sidearm. But for me the small pipes were just it. Maybe I should blame my dad because most of what I heard him playing growing up as a practice chanter, and the small pipes are a kind of a fully realised version of the sound of the practice chanter.

JLA: How did you come to love bagpipes Richard?

RY: I think I saw an open university programme as a teenager, and hearing Gaelic psalm singing, and then finding the Scottish Tradition record series, with a whole range of Scottish traditional music. Otherwise I had piano lessons and guitar lessons, and I was in bands – that was my background. We had a teacher who was quite a folky in primary school, but you know, it was The Boar’s Head Carol at Christmas services and so on, it wasn’t anything like pibroch. They don’t know about pibroch in The Fens.

JLA: Maybe because you haven’t got any hills to play them on top of [laughs]

DL: I suppose what we’re talking about is how do you get into what you get into. Pipers often have a more individual journey in music than you realise, but the family and community element is very important. Like Richard I’m a magpie for sounds that I like – with piping I just had to have that sound, particularly the sounds of the small pipes. I ended up sending away for them from a mediaeval music shop in Shrewsbury where they were made by a magnificent Northumbrian small pipe maker called Philip Gruar, who had discovered a sideline making pipes for early music enthusiasts. I still have them at home – I haven’t brought them with me to Ascension Island because of the tropical climate – they’re wood, so they might split!

KM: It’s interesting you came to the pipes late because everything that I’ve experienced as a youngster on Lewis was that you had to be in it at a really young age, it was disciplined learning. I never played pipes as nobody in my family did until my stepdad came along later. Pipe teaching in school was separate from the music class, so a teacher would come in who looked very severe, like a church elder, and it was very much an impenetrable world. He looked serious as all hell – there seemed to be no joy in the teaching of it.

JLA: I recall you telling me you would walk home from school and knew where the pipers lived.

KM: Oh, yeah, you could walk through the villages and you knew who played bagpipes because you could hear it – you knew who was a weaver because you could hear the Harris tweed loom going and you knew who was pipes player, because you’d hear it. With teaching them, it was a bit like Gaelic when I was growing up – if you didn’t come from a family who spoke it, it felt impenetrable. It was a very staid world where it was discipline and homework and not a lot of fun. My stepbrother learned pipes for a few months but got told to stop pretty quickly. It wasn’t being taught as an expressive instrument.

DL: When I think about piping in the Western Isles, where you’re from, I was aware that the traditions within particular families were very strong and often go a long way back but I’ve not often heard that kind of outside perspective on it, if you like – it’s interesting and sounds kind of forbidding in a way!

In the 90s, you still might get chewed out by the pipe major, for trying out something in a weird key or with ‘extended technique’ I guess – trying to sound like an electric guitarist or something usually! That’s changed a lot over the past 25 years in the bands though. These days top bands are pretty creative, and it’s become normal particularly for the more talented young players to get into folk and celtic music groups. I think it began with bands like The Vale of Atholl (Perth/Pitlochry) and St Laurence O’Toole (Dublin), and leading “Vale” piper Gordon Duncan. He helped bring the pipes into folk in the 80s with the Tannies [Tannahill Weavers], and took a lot of cues from his idols in AC/DC too – he got flack for the way he played from Seumas MacNeill, the College of Piping principal, but I don’t think he really gave a shit and released an album “Just for Seumas” to make his point. Obviously, it really wasn’t Seumas’ kind of album…

JLA: As you’re talking about this, I am thinking about notions of the ‘proper’ way to play an instrument – traditions and commitments to them, and how this relates to your foot guitar music Richard. I feel like you maybe have something to say about expectations and tradition and the idea of ‘proper’ playing.

RY: For me, the ‘proper’ way to play is whatever I find interesting. The foot method of playing guitar came about because I got bored. I tried new fingerings, new tunings – trying to make the guitar interesting for me again as I’d drifted from it. I really wasn’t getting anywhere, then I was on a train with my son Sorley, who at the time was maybe about 8/9. So I just said to him, how can I make the guitar interesting? And he said, just matter of fact: ‘play with your feet’. I thought that’s it! I play it with my feet! And I got a bit sucked into this and recorded probably 10 hours of the stuff. The other day, I was doing some of playing with my feet again – I got my zither out and started playing that with my feet. It really builds your leg muscles.

JLA: I remember that there was a period when you deleted everything off your Bandcamp, except about seven volumes of foot guitar – have I remembered that right?

RY: I view Bandcamp almost like a shop where there are stock levels and pop up sales. I’m not into it all being there at the same time. I like to keep people on their toes. Maybe I should put up Foot Guitar with limited seasonal availability?

JLA: Before we get ahead of ourselves, it’s probably important to say, that foot guitar might be a funny idea but you’re not just stamping around, you’ve developed a technique!

RY: Oh, totally. It sounds like it’s just it’s just messing around, But it isn’t. It became a way of playing that I got really into. You know, I still play guitar with my hands, but I got to the point where I wanted to find something new. Maybe it’s a small attention span, or that I’m easily bored, but I’m always on the look out for being excited about something. So when Donald said do you want to get together and play in the piping centre it sounded like a great idea.

DL: I was stoked because I’ve listened to Richard’s stuff. Particularly the folkier side of what you’ve done Richard. We ended up with this wonderfully brittle and spindly kind of sound between the pipes and the guitar, which was really beautiful. It was lovely to play like that, and it was very freeing for me. This time leading up to when we played together, Richard, I was making very atonal and experimental sounds on the one hand, and on the other side, I was continuing my exploration of traditional music. And when we met, the two strands finally joined again. History Of Sleep is right where my heart is, freely wandering like that.

RY: The fact that we did it in a room together, onto tape, very quickly – there was no time to actually deliberate. The choice of studio was probably a good one because it’s not overly comfortable. It’s a very intimate environment, quite scuzzy in a very good way. I’m not a big fan of studios.

JLA: So tell me the story of where Dorrington came from, as it’s one of the oldest pieces of bagpipe music isn’t it?

DL: A manuscript was rediscovered by a piper from the north of England, Matt Seattle, he’s very heavily involved in the Lowland & Border Pipers Society. And he lives in Hawick in the borders. He recognised that this old manuscript was a collection of Northumbrian pipe music, the repertoire of the old border pipe, which essentially had been lost. Of the pipers who were playing it we know about Willie Allen and his son Jamie, who were travellers that would move across and around the border. They were they were well known for various things. piping was one but they were also dog breeders – there’s a breed called the Dandie Dinmont Terrier, which they brought forward. Willie is supposed to have played Dorrington on his deathbed.

RY: Dorrington appeals to my fondness for stretching out in form. I’m drawn to things that don’t necessarily outstay their welcome, but you know, just really push it. How long can it be there? I think at the time, you said, Donald, that it was the ‘main event’.

JLA: What really spoke to me about History Of Sleep from the first moment I heard it, was that it really draws out that character of bagpipes that can be very much like a landscape – the way they can be played, and played with so that the listener pulls back their perspective of the music, and can see a whole vista – playing that has a panoramic feeling.

DL: It’s totally freestyle and improvisational, and very tonal, but mostly, there’s just this space. It’s a ‘big music’ space, if you like.

JLA: Maybe I could qualify everything I love as ‘Big music’ in one way or another.

DL: Big in bagpipes is long form and slow. Small is short notes and tight and energised and quite physical, you know. So that’s the distinction for me. It’s more in your mind whereas the wee tunes are more about physical movement and so on. It’s not an elevation thing. It’s to do with the fact that it’s long form. I go into a different state of mind when I’m listening – a kind of big music place of mind.

***

We nod and agree into our respective cameras, having found a natural end to the conversation, as the trade winds rustle and a dog barks behind Donald. Someone comes to ask Richard where their family dog Biscuit has got to. From over hills and across oceans, we wave goodbye.