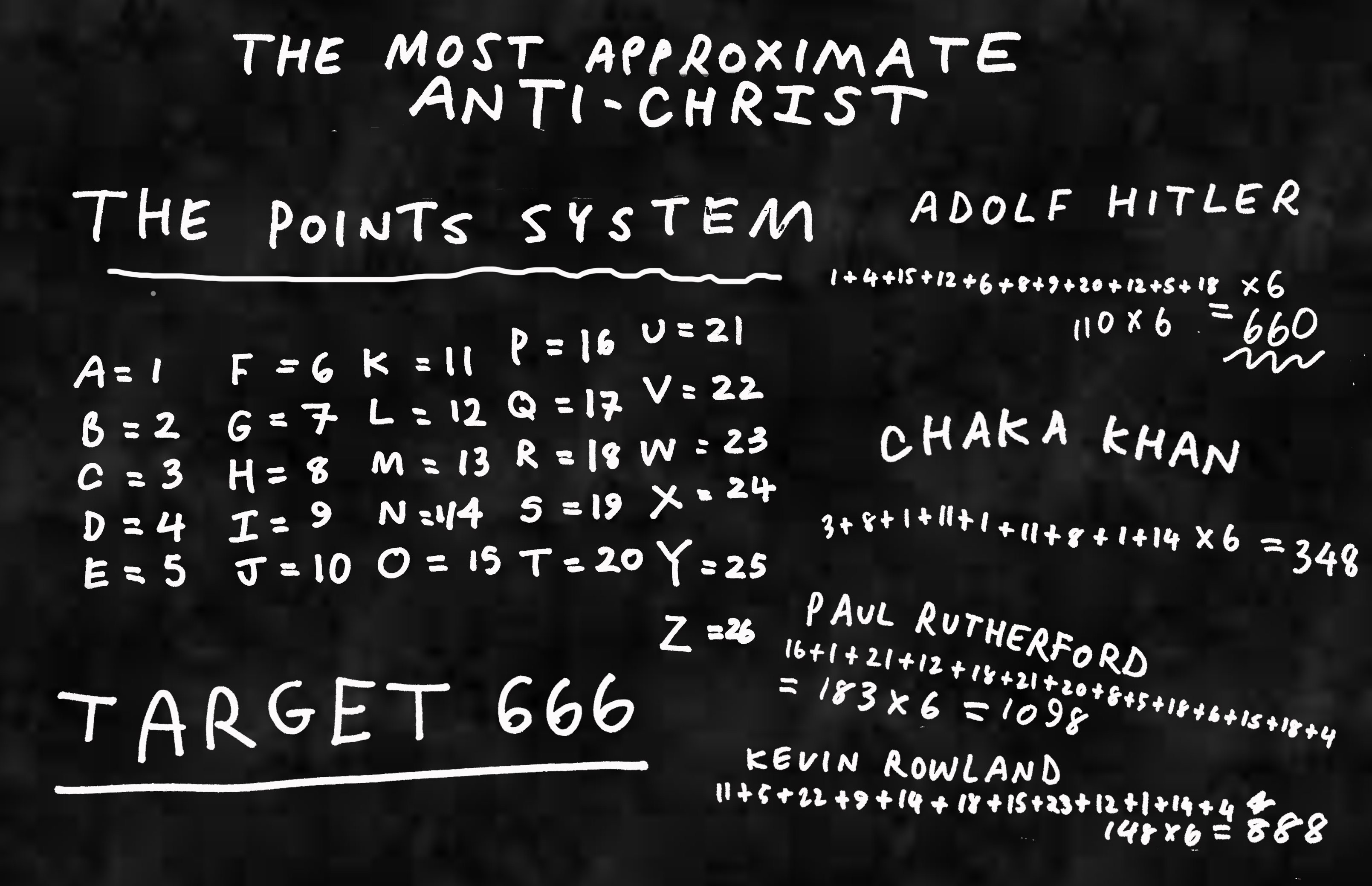

(The Most Approximate Anti-Christ Blackboard by Babak Ganjei)

—

It’s 1984, a noisy Belfast classroom at break-time and some numerology is underway in the back of a homework diary. Teen fans of the divinatory arts are determining who out of Kevin Rowland, Chaka Khan and Paul Rutherford from Frankie most approximates the Antichrist. Our mystical system is this: A = 1, B=2 and so on; add up the letters of the name and multiply by 6. The number we are looking for is 666. Adolf Hitler scores a very close 660, proof of the stringency of this way to discover who is the ultimate enemy. None of this lot makes the cut: Khan is only 348, Rutherford 1098, and Rowland 888.

We believed that saying the Lord’s Prayer backwards at midnight while looking in the mirror would allow the devil to appear. Laugh we might at the graffiti near the station – ‘We are Satin’s Slaves’ – but that misspelt word didn’t mean that Lucifer’s disciples weren’t skulking in our leafy suburban enclave. On elevated land around Belfast – Black Mountain, Cavehill – there were stories of animal sacrifice and black masses. People had seen the bones, the embers of the fires. Devil-worshippers listened to crazy music, weird sounds like you’d never heard before. These tales were terrifying and thrillsome.

Even apparent innocence presaged the strange and sinister. A few years before, I told a joke on BBC Radio Ulster, as part of a competition called Junior Jokers. ‘Why did the man set fire to his coat? Because he wanted a blazer.’ I won, and the prize that arrived a week later was an ELO 7 inch, ‘Wild West Hero.’ I listened to it a lot. But it transpired that ELO, so seemingly innocuous, were, like other agents of Satan, apparently putting subliminal messages in their music. My beloved prize had not been simply an ode to the cowboy lifestyle. The unconscious mind was something to be feared, because the devil was already inside us, waiting to be marshalled by certain signals. Somebody said that it was really weird that I got sent an ELO single. Was it? But then I did joke about burning and fire and blazes. I maybe seemed a hellfire ten-year-old already.

Belfast of course didn’t have the monopoly on this kind of thing. A friend from Shetland told me how a preacher warned of the perils of heavy metal music, inviting teenagers to take part in a ceremony where albums, cassettes and denim jackets were put in a hole in the ground which was then filled with concrete. The euphoria of purification might have been a temporary high, but afterwards there was regret. They’d been great records. In the U.S. there was fear of the occult, with tabloid stories of devil worship and ritual abuse. Tipper Gore’s Parents Music Resource Center produced their ‘Filthy 15’ records, selected for sex, drug or occult content.

The previous decade had however given Belfast a unique satanic pedigree. In his book Black Magic and Bogeymen: Fear, Rumour and Popular Belief in the North of Ireland, Richard Jenkins says that a British Intelligence Unit operating in the early 1970s deliberately encouraged fear of the occult. The unit, known as psychological operations or ‘Psy Ops’ placed black candles and upside-down crucifixes in a range of deserted locations. The intention was a cross-paramilitary smear, that violence had unleashed diabolical forces. It also had a practical function in that it acted as a deterrent to teenagers and young people who wanted to venture into derelict buildings at night for kicks.

It was certainly true that for Belfast teens in the ‘80s options for kicks were fairly limited. I, like many, ended up at the church most weekends. On Friday night in the big hall with its floor marked out with tape for badminton, there was football, clusters of people talking, even a little dancing. Kids smoked and drank round the back of the hall and the record played repeatedly was ‘Passionate Friend’ by The Teardrop Explodes. The leaders were good people. Occasionally on a Sunday night, if I got an invite, I would go to one of the tiny churches which could freestyle it in terms of religious dogma because they were in someone’s back garden or some such place. There was one where a preacher spoke about how our daily life was shaped by forces battling in outer space; this was illustrated with pictures of schlocky and improbably lurid planets that could have been on prog rock covers. Mostly though, I just went back to where I had been on the Friday. On the Sunday the atmosphere was much more devotional. It wasn’t really until I saw Spiritualized during their ‘Ladies and Gentlemen’ phase that I witnessed anything that approximated the eye-closed, spaced out oblivion of those around me as they held their hands aloft in communion with their Lord.

There were guest speakers. People gave testimonies where they talked of the path that took them to Jesus. They tended to exaggerate past misdemeanours so as to make their transformation more miraculous but it was clear that most of these supposed erstwhile motherfuckers were just as nice before as they were now. One young man who was at the local art college told of how difficult it was to maintain his beliefs in a place so ideologically challenging. He talked at length about a type of painting style called automatism which involved people losing control of their minds and letting the devil take over. He said loads of artists did this, like Jackson Pollock. I remembered the name. The next day in school I went to the library to have a look and found an example, probably Autumn Rhythm. I couldn’t see anything too evil but then I wondered if I just had an unsophisticated idea of Satan’s visuals.

I once went on a weekend trip with the Sunday night crowd. The key got lost for the barn where some of them were staying. Earlier that day we had visited a fifteenth-century friary and the key was eventually found on a wall. It had dropped out of someone’s pocket when they were climbing over it. This transmogrified into a narrative where the devil had tried to disrupt our trip and had stolen the keys, which had eventually been illuminated by the Lord. Rather than simple lost and found, we were at the mercy of battling, cosmic forces, rather like those near the Day-Glo planets.

Frequently I went with the church crowd to see a band called SOS. In fact, SOS must still be the band I have seen more times than any other in my life. They produced a familiar blues rock shuffle. In other church halls they might sometimes let members of the audience play their own music before the band came on. One time, a crowd of skinheads took control which meant that we heard Oi! classics from the 4 Skins and others before the Christian blues began.

Towards the end of Hellfire, the Nick Tosches biography of Jerry Lee Lewis, Jerry Lee is asked why he is so very obsessed with hell. He says, ‘Because Satan has power next to God. You ain’t loyal to God, you must be loyal to Satan. There ain’t no in-between. Can’t serve two gods.’ SOS, like all the rest, subscribed to this same duality. In between songs with a portentous air of doom like ‘Time is Running Out’ the singer/guitarist talked about how it was important to turn to the Lord. A regular feature of their set, however, was a shift to an acoustic guitar and a song that the guy was always quick to acknowledge wasn’t a Christian song as such, although it did have the line that ‘Jesus Christ died for nothing’. That allowed for an exegesis on how Jesus Christ did not die for nothing. It was ‘Sam Stone’ by John Prine and the guy from SOS sang it well. As a way of looking at a man’s life – in its compassion and acknowledgement of frailty, its sad and careful detail, it was in its three or four minutes superior to most of what I ever heard at church.

Wendy Erskine (score – 912, not the Antichrist either)