Happy publication day to Will Burns, whose long-awaited debut collection, Country Music, is now out! We had a big blowout launch party at The Social planned, but sadly have had to postpone it due to the dread virus.

But, of course, we’ll still be celebrating at a distance! In the evening (join us at 6pm on Twitter), tune in for playlists from Graceless Lady and Jof Owen, both of whom were scheduled to play on the night – parade around your flat with a cold michelada, or settle in and listen with a couple of fingers of whiskey.

Before that, enjoy a reading by the brilliant Declan Ryan, whose pamphlet Fighters, Losers was shortlisted for the Michael Marks Award last year. He’s opening for Will [time], who will treat us to a reading from the book, so you can hear some of the intimate, musical poems that make up this stunning collection.

And if that wasn’t enough, you can read Will and I in conversation, interviewing each other about poetry, the outdoors, travel, languages, taxonomy, Americana, pubs and hugging.

Spring is in the air. Somewhere not too far away summer is lifting its head, evoked by the poems in Country Music with its soundtrack of Chet Baker, Merle Haggard, Warren Zevon, Texan country singers and the shimmer of pedal steel. Join us all day and lift a glass of whatever you’re drinking to Will Burns and Country Music, and buy a copy of the book here (or from your friendliest local bookshop, if they’re delivering – they could do with your support!).

Martha Sprackland is a poet and editor at Offord Road Books, Poetry London, La Errante and Unbound. Her first collection Citadel is due to be published by Pavilion Poetry on April 27th. Both Will and Martha have been longtime contributors to Caught by the River, regulars at the bar, familiar faces at festivals and gigs and get-togethers of all stripes. Due to the ongoing restrictions on gatherings of more than two people, the launches for both Will’s and Martha’s books have been cancelled, so we thought an email interview between the two would prove interesting, perhaps humorous, diverting at the very least.

Martha: Will! The virus has taken our book launches. How do you feel?

Will: I feel philosophical, I suppose. I’m bound to say it’s disappointing; I love an evening surrounded by friends all slapping me on the back and sinking a few as much as anyone does, but equally, as I’d hope anyone in our position would feel, that disappointment is tempered by the knowledge that other people will be going through absolute hell in the next few months. The book’s had a long, sometimes hard (or it’s felt it) birth, though, so this does feel like yet another aspect of its seemingly innate bad timing.

And how about you? You’ve been working on your own book for almost as long as we’ve known each other. How are you feeling?

M: It’s my own fault for dithering so long, isn’t it. Oh, I don’t know how I feel. As you say, it’s sad not to be looking forward to a party, a big celebration, and to seeing Citadel in people’s hands. But it’s a postponement, not a cancellation. There are so many books this year whose launches will be postponed – we’re all in the same boat. I’ve been half-thinking that once this all blows over we should arrange just one enormous group launch for everyone whose launches didn’t happen, like a little festival . . . Is that mad? Could be fun.

Tell me about Country Music‘s hard birth. Were the poems hard-won? The subject tricky? I knew a couple of these poems intimately, of course, before we started work on Country Music, having worked with you on your Faber New Poets pamphlet, back in the day.

W: I don’t think that sounds mad, it sounds excellent.

I wouldn’t say the poems themselves are more hard-won than anyone else’s – it’s more to do with the whole process of showing what you think might possibly be a book to an editor, the back and forth of that, the doubts, the sense of feeling unfashionable, out of touch with so much else that’s going on. A sense of rejection, to speak plainly. And then of course I spoke to you about it and all that dissipated. I did the opposite of dithering, I think, and probably thought I’d written a book a couple of years before I actually had. Matthew Hollis [at Faber] was very thoughtful and astute in his set of notes on the early manuscript he saw, and certainly the later poems that went into the final draft are ones I feel much better about, so in the end I’m very grateful it’s worked out how it has. I must just be an impatient bugger, I think.

But you asked about the subject matter, and that’s something I wanted to ask you about, too. How did you put this collection of yours together? Have you felt that process change from your two pamphlets to full collection?

M: If you’re an impatient bugger I’m an absolute snail. I’ve had a manuscript ready to send out five, six, seven times over the last few years, and always pulled back at the crucial moment. It’s amazing it’s happening at all, with me as a roadblock. Speaking of editors, mine was brilliant – Deryn Rees-Jones, at Pavilion. I was quite flighty, I think, and she was great at anchoring me.

The two pamphlets were different, for sure. The first, Glass As Broken Glass, which came out on Rack Press, felt much more like a rattlebag; a gathering-together of all the things that seemed strongest that I’d ever written, so I didn’t have to think much about theme or narrative (though I definitely see unconscious threads through it, now). And then in 2018 I did Milk Tooth on Rough Trade Books, which was totally thematic – that one was a bit more hard-won, I guess. The subject matter was tougher, slightly embarrassing, painful, or exposing, at any rate, so publishing it felt like a real flag-planting. Citadel couldn’t have come about without Milk Tooth – moments, conversations, and events that are only ever alluded to in Citadel actually exist in Milk Tooth, as if the one can be read as a key to the other.

I needed this other voice to write it, I think – the poems in Citadel are a sort of collaboration between the narrator, the city of Madrid, and Juana la Loca, the sixteenth-century queen of Spain. I suppose it adds a layer of plausible deniability for all the voices – it’s both exposing and shielding, which is partly what the citadel is in the first place. It’s about both attack and shelter.

If Madrid and Merseyside are the ‘places’ of Citadel, maybe Buckinghamshire is one of yours, right? But not the only one – Country Music has a strong American flavour, too. Where does the book roam, do you think, and what do those different places do for it?

W: I like that double-sense the word ‘citadel’ carries, I suppose I’m trying for those kind of slippages with my places as well. As you say, there’s Buckinghamshire, where I grew up; London, where I was both born and then later spent most of my adult life, and there’s some poems from France and from Jersey, where my wife’s from. That’s been an interesting place to spend time in the last couple of years while we’ve been dealing with the implications of the EU referendum and excavating our relationship with Europe. If you could describe the process as one of fragmentation, then the Channel Islands are a kind of physical embodiment of that – little fragments of land floating off the continent, loaded with all this post-Norman history, a very specific experience of World War II, dying languages, tax havens. All good, heavy stuff.

Then there’s this sort of version of America. I think most people my age, growing up here, experienced almost all our culture as drenched in this Americana – the era of MTV, Spielberg films, and clothes, even fast food. It seems quite different if you happen to be teenaged now, so much more inclusive, global. There were exceptions then, of course – notable ones, too, like rave culture – but I think the extent to which America permeated the Western imagination since rock’n’roll, say, is quite strange, quite profound and also discomfiting, unhealthy, and ultimately open to all sorts of exploitation and violence.

We’re living through a particularly nasty hangover from all that, I think.

I don’t try to get that big, socio-historical stuff in deliberately, though. I’m with Richard Hugo when he says that if what he calls the ‘triggering subject’ is too big, the mind shrinks. I want to start from the very local, the small, the specific.

Where do you think your relationship with Spain has come from? I know you’re a very skilled linguist; I’m interested to know if your love or captivation or however you would describe it of languages led to you to the geographical fact of the country, or vice versa?

M: It’s a world you know much better than I do, I think, that Americana – both real and in the cultural imagination. I grew up listening to a lot of my dad’s music, and although there were plenty of Americans in there, of course, a lot of it was also European folk, and as I kid I was pulled that way, first of all.

I found it so strange to visit America – I spent a few months there at a writing retreat a couple of years back, in upstate New York and then Brooklyn, and did occasionally have to shake my head to clear it. The size of everything. And the youth of everything, too – I saw houses with plaques on them noting that the building had stood there since, I don’t know, 1880 or something. And as a European, obviously, you think something like Uh-huh? So what? And perhaps more pressingly – And what was there before that? No different to here, I guess, just newer. I’d like to see more of it. Wyoming, Oregon, the border states. Now’s not an ideal moment, perhaps.

And then of course as a teenager the pull was very much towards the continent, towards Spain in particular. I remember going to Madrid for the first time when I was sixteen or so and thinking Aha! Ha ha! Yes! I tanked my A-levels, so I decided to go and do teacher training instead of university – packed my stuff, broke up with my boyfriend, and moved in with an English teacher in Moratalaz, down in the southeast corner of the city. It’s my favourite place, really. I feel at home when I’m there in a way I never have in London, my other adoptive city, though I’ve been in London eight years. It’s not quite a fit.

Part of it is the language, you’re right (though Spanish was one of the A-levels I failed, I do speak it now). I’m obsessed with language-learning – I suppose I’m the kind of writer who sees individual words as material, as the necessary stuff, so learning another language doubles your word-hoard. Learning another one triples it . . . I know some people don’t have much truck with chunks of untranslated text in poetry, but I love it, whether I speak the language or not, I love reading it. Poetry is only half meaning, isn’t it, and half sound, so what an unfamiliar word does on the tongue is just as important as what it does in logic. Anyone can look a word up in a flash, now. That’s my justification, anyway, for leaving big dollops of Spanish all over the poems in Citadel.

You came over to Madrid to read, didn’t you, last year, at Desperate Literature. What did you make of the city? And do you feel at home in London? I know you’re not here all the time, but this is where you and I have spent a lot of our friendship, isn’t it, down at The Social, when we’re not off in a festival field.

W: You’re spot on about the half-meaning/half-sound. Or rather, maybe, the sound carries some meaning of its own, in harmony or counter-harmony to sense, or something like that. Cleverer people than me could explain that far better, no doubt. I love that section in Don Paterson’s big book about phonosemantics. I agree totally about words being the essential material too. I absolutely love learning bits of new languages, but I wasn’t much of a linguist at school – I did Latin and always had that sort of bent. Old English at university. Dead languages, the old gods.

I loved Madrid, and of course we had a great time. I’d need to see more I think, to feel at home, but I can appreciate your feelings for it. I have a similar thing for Paris, where I’ve got lots of friends and try to spend some time every year. And yeah, I feel very at home in London. I still find it so exciting to be in London – the pubs, the record shops, the bookshops, the river, the galleries. I need the hills now, though, and my garden.

Do you see yourself as a perpetual city-dweller? Or is there a year or two in some isolated rural location on the cards?

M: Forgive the shameless Poetry London plug, but Joey Connolly writes about the sound–sense thing really well in the latest issue. He says this:

‘sound matters in a poem: a word’s noise complicates the neatness of its dictionary definition, and this effect multiplies exponentially across a line, a sentence, a verse. Sound and sense, in poetry, mutually unsettle one another, so that paraphrase – the great clarifying tool of conversation or textbook – is disallowed.’

I think that’s just about perfect, isn’t it?

Funny, you know, I don’t think I actually am a city-dweller. I think Madrid caught me up at just the right time – I was a wild teenager, and Madrid was this responsive, hedonistic place that met me exactly where I wanted it to. Sound and sense did their thing together. London is a bit too siloed, for me, a bit too stretched out. And I know people have different experiences of it, but I find it a bit suspicious. Not very tactile. I’m an oversharer! Maybe a city can’t really have these personality traits, though – maybe I’m talking more about the way I behave when I’m here, versus the way I behave when I’m in Madrid. But then you asked if I was a city person. No, I think I’m happiest away from the city. I haven’t found it particularly easy to settle anywhere, to be honest, even Madrid – perhaps I’ll be shuttling about forever.

I was in Paris just before Notre-Dame burned, doing a reading at Shakespeare & Co with A. K. Blakemore. It was very strange to feel like we’d been so close to A Happening. But now it feels like we’re right in the middle of one, doesn’t it – not even proximate, but turning in its eye. Can we talk about the virus? Should we ignore it? I have a real compulsion to talk about it all the time. Is your life different, these last couple of weeks?

W: That is good, yes, that Connolly bit. I think of poetry as perhaps having the potential for some kind of knowledge beyond the merely categorical, or in linguistic terms, as Joey says, the narrow sense of a current dictionary definition. I think that word current is important as well, because a poem, through sound, maybe, and other techniques, can excavate the past meanings or senses of words too.

I remember seeing that you were in Paris at that time. I think the only time that I can remember anything like we’re going through right now is working in central London on the day of the bombings. I remember being on a bus into town with my brother (we worked together at a record shop at the time) because the Tubes were down. This was just before the ubiquity of smartphones, so the news wasn’t spreading quite as fast as it would today. But our Dad phoned me and told me to just get off the bus as soon as we could. All day we had one customer. We didn’t leave this little basement, just sat and listened to records, glum and quiet. But the strangest thing was the end of the day, about six, when there was still no public transport in central London, so there were hundreds of people streaming over Waterloo Bridge to get buses and trains from the south side of the river. The phrase I’ve heard lots the last week or so is people feeling like they’re living in a film, and that moment really had that quality.

We shouldn’t ignore what’s happening, no – it’s why we’re having this conversation, after all. I’m exactly the same, finding it hard to read or talk about much else. My life is different in some ways – the fishing shop I work in part-time is closed; my parents are publicans and they’re closed so I’ve gone from seeing them every day to not seeing them at all. But I work at home a lot, and my wife works at home too, so that’s not been such a shock. How’s your day-to-day life changed? I think we may have a very different country when we get out the other side.

M: My day-to-day life has maybe changed a little less than most. I was already freelance and home-working, so the main difference for me is just that everyone else is complaining about bad internet connections and frustrated naptimes, now, too. Money looks precarious. I’m worried about that.

I feel less isolated, perhaps – a strange outcome of isolation. I’m in lockdown with E, the person I’ve been dating (for not a particularly long stretch – it was a bit lose-it-or-leap), south of the river. We’ve both been quite studious with our freelance work (he’s a teacher, now all online), which means the days have a nice quiet shape to them. I’ve been out running a fair bit, though it seems to make people angry, round here. I have some pathetic, optimistic little idea that I’ll do calisthenics every day, like someone in captivity in a film, and emerge from lockdown with rippling muscles and rock-hard abs. And maybe another language.

But really I’ve been doing Zoom pub gatherings, Skype family lunches and all that, though it’s not the same, is it – I miss the tangible world! I miss touching things. I realised the other day that I’ve only hugged one person in the last seventeen days. I wonder what it will do to us, all this withdrawing? Will we become more insulated, somehow? Or perhaps we’ll all explode out of lockdown, desperate for attention, into a slavering, orgiastic mêlée of physical contact.

Funny you mention the London bombings; I was thinking about them the other day. I wasn’t living here, then, back in 2005 – I was in Merseyside, still, a couple of months after my first visit to Madrid – though I remember it on the news, of course. Did you read that collection about the 2017 attacks, by Richard Osmond – Rock, Paper, Scissors? I’ve been wondering what the writing out of this pandemic will be like. There have been some brilliant books written in response to cataclysmic events, haven’t there – Jay Bernard’s Surge last year was phenomenal, I thought, writing about the New Cross fire and the Grenfell disaster. I wrote a sort of pandemic-poem, the week before last, right at the beginning of the shutdown, and it was fucking terrible. I’ve decided not to write any more about it, none at all, until 2023 at the earliest.

W: I didn’t read Richard Osmond, but I agree the Jay Bernard book was incredible. I wonder if a bit of time elapsing after events of this sort is somehow necessary though. I feel, though it’s instinct as much as anything else, that some sense of perspective on things enriches the reaction in some way. Jay Bernard’s book travelling across time to discuss those two incidents kind of allows for that. I think I’ll probably carry on writing my little poems about being a bit sad while looking at one kind of bird or another, but who knows?

The online socialising isn’t the same at all, though it’s still good to see friends and talk to family. I’m put in mind of my teenage years, when you spoke to friends on the phone a lot. I went to a school that had a huge catchment area, so your friends might live miles away. Everyone’s first relationships relied a lot on the phone too. Now I don’t know anybody who answers the phone most of the time. They are messaging machines more than anything.

I very much miss the pub, though. I love almost everything about pubs. Even, it turns out, on some level, the things that frustrate me. It will be fascinating to see what the social world looks like after all this. I suspect it depends a bit on how long the lockdown goes on for.

While we’re talking about what we’re doing to keep healthy and all that, I wanted to talk to you about gardening. I know you’re very keen – have you access to any sort of garden at present? What is it about keeping a garden do you think that is so affecting? Auden insisted all students should cultivate a garden in his ‘daydream College for Bards’, and Wendell Berry feels it has the same sort of importance. Obviously Alice Oswald is a gardener too . . .

M: Do you remember what pubs used to smell like before the smoking ban? I remember the day that ban came in, and we all stayed up for a lock-in, smoking ourselves sick. Your lovely pub in Wendover smells nice, though. I walked past a pub the other day – not one I’d ever been in – and found it suddenly very odd to imagine being in there, shoulder-to-shoulder with other people. Seeing people right up close; being in a crowd. Remember festivals, Will? Remember clubbing? I bet you don’t remember clubbing.

There’s a garden here, yes, with a couple of rosebushes in it, and a glorious magnolia tree in full bloom. The birds have been swarming over it, now that the city is quieter. I haven’t done anything to the garden, because it’s not mine, except sit out in it drinking café bombón. On the day the lockdown was announced we had this split-second decision to make – I’d been staying here at E’s house, and it was either make a mad dash north of the river to fetch enough of my things that I could lock down in Lambeth with him, or else pick up my rucksack and commit to my flat in Hackney by myself . . . so we ended up driving there and back over Tower Bridge late at night with the car full of my rescued plants, including the Christmas cactus I’ve had for years and schlepped around everywhere. They’re pretty tolerant of being moved, now, given how long I’ve been itinerant. They seem to be taking to it OK here in the south.

I don’t know, in answer to your question. I could say something about the act of growing things from seed, and the way that it’s like nurturing an idea, I suppose. I can’t quite muster that – it’s pretty, but too sugary. I think a lot of the good it does is in counterbalance to the decidedly cerebral lives we live, as writers, editors, whatever. I can feel my brain pacing the floors, sometimes, and gardening – that steady, often repetitive physical work, the sense-data of the living world, sweat and dirt and light and change – quiets it down again.

I did a horticulture course a couple of years ago, and noted that part of the joy of it, for me, is still in language – the etymology of plants, the way their names give clues to their functional, medicinal, mythological pasts, and in doing so tell us something about our own relationship to them. And to eat something you’ve grown feels guiltless. It’s hard to feel guiltless about almost anything we eat, in the city.

What’s in your garden? I remember setting foot in it, briefly, a couple of years back, when you and Nina were giving me a lift to some festival or other. Sea Change? Anyway, you had a lovely little shed. What do you grow? What does it do for you?

W: This is going to sound very strange, as I have never even tried a straight-up cigarette in my life, but I very much missed the smell of pubs after the smoking ban came in. Lots of strange shards of nostalgia. For example, we always used to go for a pint on Christmas Day, and it was almost my favourite bit about Christmas, standing with the grown-ups, listening to my Dad and Mum talk about the things they talked about – music, books, politics. And I always remember the smell of the pub on me for the rest of the day. They were some of my earliest times in the pub, and I just loved it.

I have to say you’re right, I was never much of a clubber. I can’t dance and it involved the wrong kind of drugs for me. When my mates at school started mucking about with pills and dancing I was into skateboarding, hip-hop and weed, and then after we left school it was playing in bands and drinking. I never fell for ecstasy the way all my mates did. Feeling as if you love everyone? Hugging? For fun?

I know you said you aren’t going to write about any of this for a couple of years, but that is a great short story you’ve got there, the tale of this on-the-cuff decision and then what to take, and which place to choose. The Christmas cactus. But I also know you hate short stories. Or so you told me once.

That’s interesting what you say about the language of horticulture. I still feel that kind of thrill with birds, I think, especially if I’m somewhere new and learning new names. I loved these birds called grackles when I was in Mexico, mostly because of the name, but then the birds became the name, and so on . . . But I’ve grappled a lot with the implications of taxonomy, whether it separates us from true experience – whether it puts a metaphor in the way of life. It’s fertile ground (pardon that awful pun) for poetry anyway.

We have the usual cottage garden plants in the house garden, as well as a few other bits that my wife is fond of. Then we grow veg on our allotment. It’s evolved into a neat division of labour. I sort of do the plot, and Nina the garden. We bought a tree for each other for our wood wedding anniversary, so my favourite plant in the garden is the rowan that was Nina’s gift.

I think what I really get out of growing things is this sense that utility doesn’t have to be at odds with stewardship. In fact, that the two ideas are intimately linked. It feels, to me anyway, like an endeavour that is radical in its rejection of so much that late capitalism takes as inviolable. Tending a bit of earth, enriching the soil, but also using it; it’s a way of truly living in the world, isn’t it?

How about we wrap up with one final question, notwithstanding the slings and arrows and all that, if you could choose, how would your first day after all this play out?

M: Did I say I hate short stories? I don’t. I don’t know why I would have said that – maybe I was in an awful mood.

Yes, I know what you mean about taxonomy. It puts me in mind of that Sharon Olds poem – what’s it called? ‘Bestiary’, I think. It’s about her son ordering the world of animals, understanding differences, angling himself to the world . . . Here, I’ve found it. It ends:

he thinks about lynxes,

eagles, pythons, mosquitos, girls,

casting a glittering eye of use

over creation, wanting to know

exactly how the world was made to receive him.

If you can tend without being rapacious, by stewardship, as you rightly call it, then I think you enter into a better, more valuable sort of compact with the living world. So many of our natural processes are weirdly truncated, end-stopped, forced – it’s a pleasure to watch processes happen, their circles and cycles and self-perpetuating, and even more satisfying to weave yourself into that chain in a harmonious way. I don’t know.

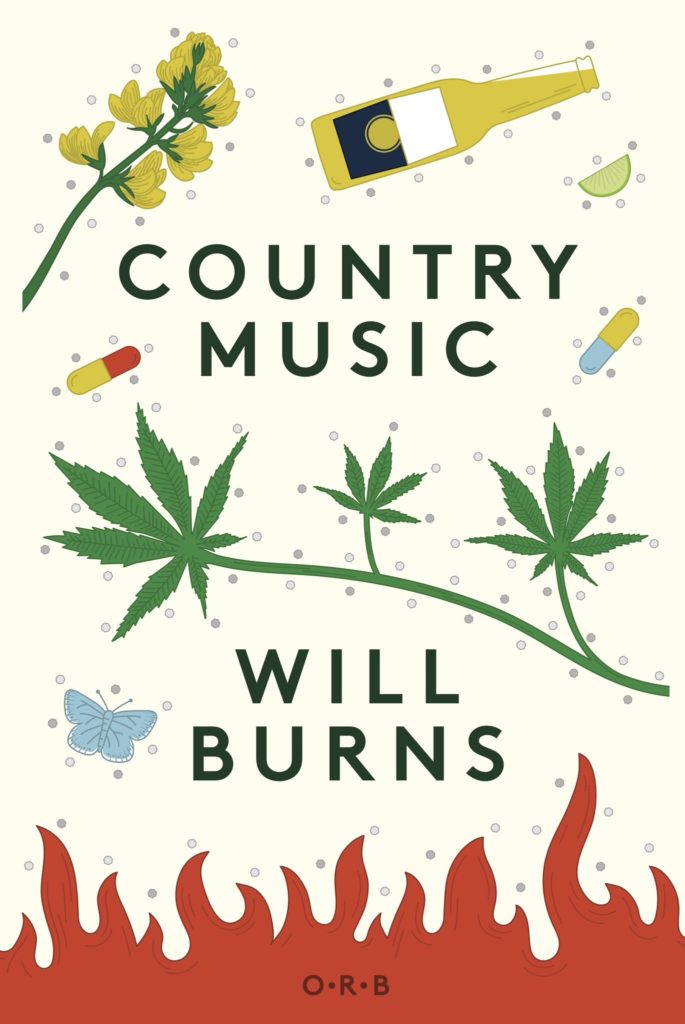

Anyway, you said stop, didn’t you, so we should stop. We’ve rabbited on. Have we talked about the books enough? Maybe you could tell us a little bit about the phenomenal cover of Country Music. Funny time to have a Corona-style beer-bottle on a book jacket. We couldn’t see that one coming. But it’s amazing, that artwork.

My first day out of lockdown . . . I can hardly conceptualise it. I will try and get to Spain, soon as I can, and maybe climb into the mountains with some friends and swim in the waterfalls. Or else we’ll have a stroke of luck and get up to Green Man as planned, Will, for our event, and mob around in the Beacons for a few days. Or a beer garden somewhere green and humming with bees, hot sun, good music and everyone we miss. What about you?

W: Well, I would happily chat away all day, of course. Without wanting to show too much of what goes on off-stage though, I’m aware we need to send this thing off . . .

That Sharon Olds poem is on the money, exactly. The ‘glittering eye of use’. That about covers it.

The cover, yes, well that’s been lots of fun. My wife Nina and I are friends with two wonderful artists and designers, Anna and Roger, who make work under the name Crispin Finn. We’ve done a few things together, including some images taken from gardens actually, some seasonal objects, alongside very short, almost fragments of journal-entries. Anyway, I asked if Anna would be up for doing the jacket and we talked about the influences, combining Gram Parsons’ Nudie suit with the things of the book. I think she’s made something far beyond what I had in my head. It’s my favourite bit of the book, part from one page, which I won’t go into here . . .

How about yours – did you get to choose the colours?

I think my first day would be very simple. London, definitely, I’d want to go out for lunch with Nina, then an afternoon spent with friends and family. Your beer garden sounds the perfect venue. So many people are going to have a totally different, in many cases diminished, family- and/or friendship group after all this, and I can’t really get past the idea of just sitting with them, talking, laughing. But yeah, let’s aim our hope towards Green Man and a few other shindigs towards the end of summer. We’ll have a big joint one for these two books, right?

M: It looks brilliant, your cover. People are flaunting it all over the place already. We’ve played a blinder.

Yes, I chose the colours for Citadel – I had an old postcard of Madrid stuck in the front of a diary for years. It shows Puerta del Sol in the city centre, the most landlocked centre of the most landlocked city in the country – the pole of inaccessibility, almost – where there’s a brass plaque in the floor showing kilómetro cero, the convergence where the old radial roads meet. The postcard shows the view towards the terracotta decorations of the Post Office, over the head of the mounted statue of Charles III the ‘mayor-king’, who is framed against the ringing blue sky, and all the surfaces and edges of things picked out in hot yellow-white.

We’ll launch them properly in that dream of a beer-garden, yeah. Everyone we love in one big open space. Shall we end with a poem? Can we have one from the books?

W: Ah, OK. How about a short one, named for a Big Star song, so apt for The Social maybe.

Thirteen

The train stations of middle England

with their ‘Parkway’ epithets,

fried breakfasts and untidy homeliness.

A couple of buzzards, farmland.

Almost nothing to see.

I notice a certain harmony

for the first time on an old song.

Something I must have been missing

for years – as if it had never been.

I wonder what it would feel like

to talk to you once more about that small noise –

that near inaudible voice.

from Country Music (Offord Road Books, 2020)

Will’s also recorded a very short video of him reading a couple of poems from Country Music from the sofa in his cottage in Wendover. Here he is…

Here’s a cracking poem from Declan Ryan, who was supposed to be reading tonight. Declan is a poet and critic born in Ireland and based in London. He was named a Faber New Poet in 2014, and has subsequently published a second pamphlet, Fighters, Losers, which was shortlisted for the Michael Marks award in 2019.

Obviously we’d have hope to have got the readings done and dusted, clinked a few glasses and got some records on, but that was not to be. We’re very grateful though, that a couple of the good folks who’d agreed to bring a few records along on the night have put together a couple of playlists for us.

Put your hat on and have dance. You’re allowed to wear your hat indoors. Just this once.

Jof Owen is a singer-songwriter and the lyrical genius behind both Legends of Country and The Boy Least Likely To. He grew up in Wendover, Buckinghamshire. Here’s some thoughts from Jof on this strange, strange year…

‘I had so many plans for this year. Big plans. I was back in the studio with Legends Of Country, and we’d almost finished recording the first single for our next album. Just hand claps and backing vocals left to do. We’d even been booked for a couple of shows over the summer, but they might not happen now either. All I’ve got to do now is watch Gilmore Girls and make end-of-the-world-themed Spotify playlists. I was supposed to be DJing at the launch of Country Music, Will Burns’ new book of poetry, but that’s not happening either. I was really looking forward to it, too. It would have been a fantastic event with some incredible networking opportunities. These are probably the songs I would have played if it had happened. Back-to-back country party bangers. I don’t suppose anyone’s in the mood for that sort of thing at the moment, but it’s here for you just as soon you are. Keep safe. Keep it country.’

Graceless Lady used to be found spinning tunes, dancing and spilling wine at various cosmic american and folk music hangouts in London in the early 00s, which is where she first met Will. Her alter-ego, Lucy Evans, is a producer of TV documentaries.

Order the book from:

Offord Rd Books – https://www.offordroadbooks.co.uk/country-music

Caught by the River – https://caughtbytheriver.greedbag.com/buy/country-music-by-will-burns/

Drift Records – https://driftrecords.com/products/will-burns-country-music