In 1703 a student returned from studying at Oxford to the family home in Worcestershire. His name isn’t known – it might have been Thomas Appletree – because he did not mark his name in the weather diary he kept that year. While his diary predates the Met Office by 150 years, even by the poetic standards of the scientific writing of his time, the 1703 weather diarist was – to put it mildly – an unusual writer, one with a lusty and weird flair for meteorological description.

Jan Golinski transcribes some febrile and oddball portions of the 1703 weather diary in his book British Weather and the Climate of Enlightenment. Many of them are charged with the erotic preoccupations of a 23-year-old – there are bosoms, wombs, sperm but also vivid (less X-rated) metaphors. The extracts Golinski published made me wish there was a complete transcription of its tightly handwritten script. Golinski writes of how he calls clouds “sky-cubbies or udders cloudy,” which “enclosed and stufft ye whole visible Hemisphere in colour like lead vapours or a tall fresco ceiling, or marble veined grotto”. Rain is “spermatic irrigation,” “milk shed from heaven suckt by each infant plant” and also, in a moment where his writing takes a particularly arcane and gastronomic turn: “Balsamic Panspermicall Panacea Juice Of Heaven”.

Aside from providing album titles for my future underground music, I also found the weather diary to be one of the more compelling tangents I traced when researching people’s relationship with the weather. It is an anomaly: deeply esoteric, deeply odd (from my contemporary perspective), and excruciatingly erotic. It’s also a text in which a writer pushes a form, strains (bulges?) against the limitations of language, and bursts through into his own crude, mad and idiosyncratic style. The mission to reinvent and repurpose language so it can adequately describe the weather is one the diarist is explicit about:

“Our language is exceeding scanty and barren of words to use and express ye various notions I have of weather etc, I tire myself with Pumping for apt terms and similes to illustrate my thoughts and yet must own a deficiency and I cannot invent a language commensurate to [the] vast and infinite properties discoverable in meteorology.”

The romance of the Shipping Forecast is one way to express time, weather, and place, but I’m seduced by the grotty and fecund prose in this anonymous diary. To thrust outwards and upwards with words and to try and represent the enormity of sky and weather, the movements, shifts and stasis found there, and to hit on fertility and coitus – the creation of life and the little death – as a way to express it, makes a sort of perfect sense. The fragments he includes are bubbling, bursting eruptions of prose, that make a sort of hallucinatory (and smutty) logic.

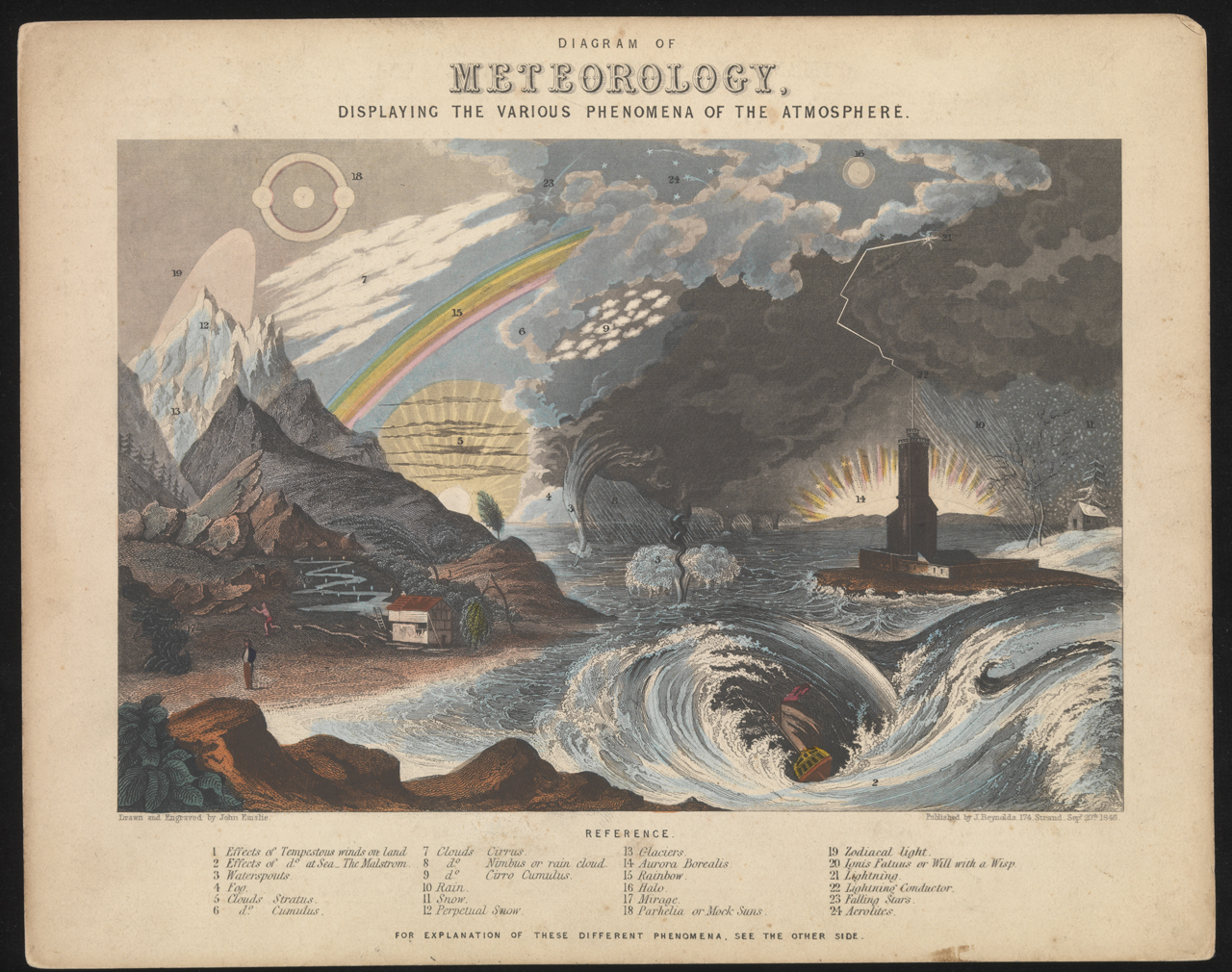

What the Worcestershire diarist was undertaking was his own special sort of observation of the weather. Weather watching as a Western practice became a widespread practice during the Enlightenment, but it is not an exclusively Western practice. All cultures have weather lore – Aristotle’s Meteorologica takes from Egyptian, Chaldean and Babylonian accounts of the weather, and a century before Aristotle, during the Shang dynasty (1600 BC–1046 BC), Chinese scholars were weighing the moisture absorption of charcoal to calculate humidity and measuring the weather using devices such as bamboo snow measures.

Weather watching is one thing, but weather prediction is a much more nebulous and difficult business. Proverbs relating to weather are transcribed in Hesiod’s Works and Days as aphorisms concerning when to do certain tasks: do not plough the good ground at the solstice, and go sailing in spring “when a man first sees leaves on the top-most shoot of a fig tree”. The Shepherd of Banbury’s Rules To Judge of the Changes of the Weather was a well-read text composed by John Claridge in 1670. it shows how to tell the time by the stars or the sun, and what to expect given certain weather conditions. It contains a month-by-month breakdown advises things like a flood in March being bad for harvest, and has a Q&A section which asks how to read the weather by the mists. There is some mystery around it though, as the ‘shepherd’ at the centre of the book may never have existed.

The weather diarist writes in a particularly vivid style, into the 19th and 20th Century, scientific writing on weather drew away from the astrological and amateur, and the poetic was lost in favour of impersonal readings based on figures and charts (although these were not formalised, posing their own problems of collation). However local lore and proverbs about the weather were not simply rendered obsolete by the emerging scientific knowledge – you’ll still hear ‘red sky at night, shepherd’s delight’ in the UK – but became intertwined with new knowledge in a complex and nuanced relationship that still requires the exercising of superstition, folklore or uncertain prediction. Even now, weather reports are still wrong – as I sit here writing, rain hammers against the window, although my Met Office says that this specific location is just a bit cloudy.

The weather remains intractable to most of us, Met Office or no Met Office – due to the scientific complexity of meteorology, and the often localised nature of weather, particularly its capacity to change abruptly. The boundaries between ourselves, our communities, and the weather, are fuzzy and we are inextricably linked. To write about weather is to write about time, eternity, and is to simultaneously write about the whole world and to nothing at all except ourselves and the tiny patch of sky above our heads – whether what we see when we turn skywards is a cumulus cloud of dense vapours, or a bulging udder.

Jennifer Lucy Allan

Preorder ‘The Foghorn’s Lament’ by Jennifer Lucy Allan from Pages of Hackney here