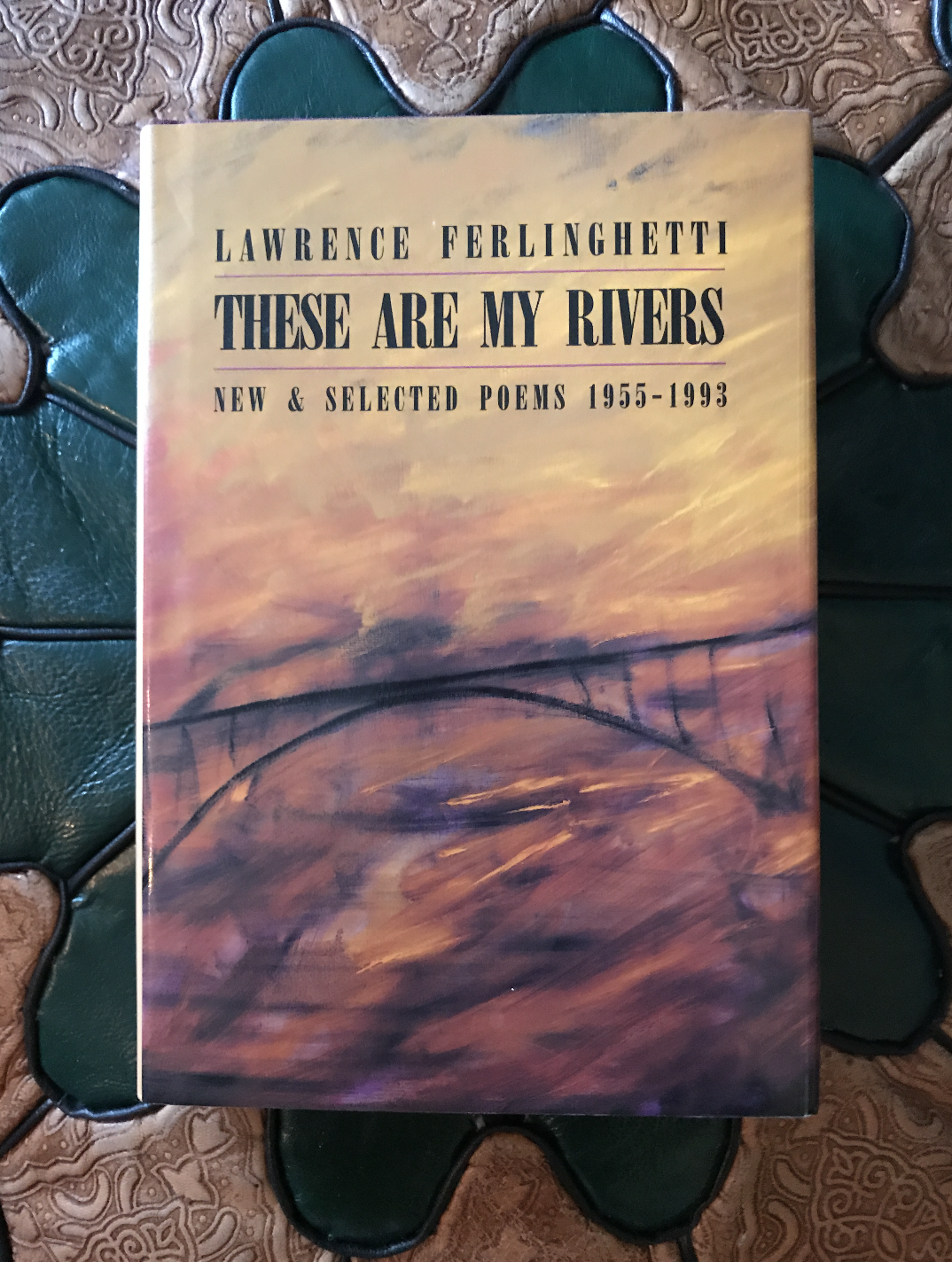

In 2009, on our honeymoon, my wife and I went in search of Lawrence Ferlinghetti on the west coast of the USA. We carried two books with us, Ferlinghetti’s 1993 New Directions collection, These Are My Rivers, and Big Sur by Jack Kerouac. In San Francisco we dropped into City Lights Books and asked if Ferlinghetti was around, but we were told he was spending time at his cabin in Big Sur, the same cabin that Kerouac had stayed in and that he had slowly gone mad in, and where he had written prose and poems that were the syllabic sounds of the sea raised to the power of tongue.

We hired a soft-top cruiser with a CD player so we could blast a bunch of Grateful Dead bootlegs as we drove down the Pacific highway. We had no idea where we were going, we were using Big Sur as a guide to finding Ferlinghetti’s Big Sur, and it was confusing as hell. We got to the Bixby Canyon Bridge and could see the ocean below. There was a dirt track leading off the highway, but Kerouac had arrived at night and talked about climbing down rocks and hearing the roar of the ocean to his right so we decided to climb down into the canyon below and walk in that way. It was totally perilous. Some clueless Japanese tourists thought we knew what we were doing and followed us halfway down before realising we were lunatics and giving up. And then we came to the sea, and it spoke, exactly like it did in Big Sur, at Big Sur, as written by Jack Kerouac. I opened These Are My Rivers at random (these are my rivers, I thought, as I looked out on all that ocean) and I started reading. “Back Roads To Far Places” from The Secret Meaning of Things:

Bashō would have liked/a lake like this/back roads/to far towns/reflected in it/As morning/mocks its flowers/by becoming/Afternoon/And when the white Furze/stands up/on the dandelion stem/it is time/to blow/Ah day is done/Day/is done/And fish float/through the trees/eating the seeds/of the sun/Papyrus and bamboo/in the window’s weather -/East > West’s leaves/tangled together/Sunlight/casts its leaves/upon the wall/Wind stirs them/even/in the closed/room/Last night a longing/a roaring in a sea shell/a confused murmur/of birds + men/And bodies/were boats/A flutter of wings/Sound and weeping/fill the air/And the quivering/meat wheel/turns.

Right there, we had found Ferlinghetti, in Big Sur, and in all the oceans of the world.

Since then, he has been my favourite travelling companion. Who can *see* like Ferlinghetti? I love to sit with him best in cafes in wide-open European piazzas and watch with joy the myriad arisings of the moment, or on, say, an early morning bus in Mondello, say, in September of 1984, or what about in the Mexican Night of 1969, the Mexican Night journal that accompanied my own Mexican Night, where he talks about the shoes of Mexico, of Mexico’s obsession with shoes and shoe shops, which I notice every time now, which is why I only buy my boots in Mexico now, now that Ferlinghetti noticed it for me. “Two hours in this town” he writes of Veracruz, in Mexico, “and I feel I might live forever (foreign places affect me that way)” That’s exactly how I feel about Tijuana (but then foreign places affect me that way).

Would I even be here, be there, in Mexico, in Big Sur, here in Glasgow, writing, if it wasn’t for Ferlinghetti? If City Lights had never published their Pocket Poetry series, even – Howl and Other Poems, Pictures of the Gone World, Save Twilight, The Love Poems of Kenneth Patchen, Gasoline, Robert Duncan’s Selected Poems, Malcolm Lowry’s Selected Poems, Here and Now, Pomes All Sizes,The Scripture of the Golden Eternity, Hotel Nirvana – how different my life would be. I hate to imagine it.

And what about his unintimidated defence of “Howl”, Ginsberg’s poem, against obscenity charges? We need outlaw prophets of religious eroto-mania more than ever. In 1953, when City Lights Books was launched, it was the first all-paperback bookstore in the USA, which was the punkest move of its time.

But most of all, Ferlinghetti makes me want to LIVE. His work, his ethos, his example, sounds a resounding yes to all of the yes to be had. His books point you out, once more, into the world, and it is made new, as it always truly is, by Ferlinghetti’s wonderful command of beginner’s mind. He writes like he is seeing things for the first time, every time, which really, you know, is the truth. Everything is new and risen up and blushing in its perfect moment, and Ferlinghetti’s poems point to this again and again, the virgin ground of eternity is the map of his poetry. I wept like a little boy when I read his final memoir, Little Boy, published by Faber & Faber when he was 99 years old.

But it’s the final lines of the last entry in his travel journals, Writing Across The Landscape, that I turned to when I heard that he had died, and when I remembered our search for his cabin, in Big Sur, back when we were newly married, and which in the end, we never found.

“Away then away/in our custom-built catamarans/over the hills of ocean/to where Atlantis/still rides the tides/or where that magic mountain/not on any map/wreathed in radiance/still hides.”

Lawrence Ferlinghetti will live forever, because poetry says so.

David Keenan