This month saw the publication of Australian author Jamie Marina Lau’s UK debut Gunk Baby – a cutting critique of consumer culture that gets to the core of the dangers of chasing a capitalist agenda and what happens when our lives are taken over by the ‘things’ we fill them with. In her exclusive piece for the Social, Jamie interrogates this very obsession and our persistent tendency to equate our things with ourselves; to attempt to control the spaces around us, to make them ours. We hope you enjoy it.

I was wondering which way to look, because often when you face towards the window you are distracted by its view but if you face towards the kitchen, then you are reminded of the many things that are supposed to get done.

*

If you Google ‘why do we buy furniture’, the featured panel reads this:

There are many reasons for buying furniture, but the most important underlying reason is that it is the backdrop to our lives. … We need furniture for more comfortable lives and use it for storage, for sitting on, and for sleeping. Going beyond the basics, it is also there to express our sense of style.

So when I developed an obsession with Facebook Marketplace, with looking for small whittled things at vintage stores during the beginning of last summer, even before I had moved into the apartment – it must have had much more to do with my desire to enforce the essence of myself into a new space than it did with practicality.

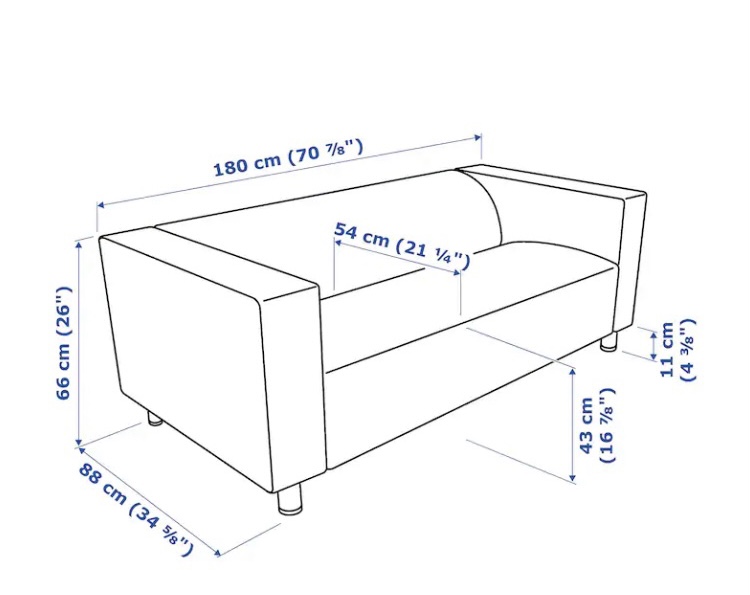

Most of the items saved in my browser were non-essentials such as ‘entertainment units’ or ‘buffets’ or hybridised plate-bowls. There had also been an incident with a drastically petite, but fashionable Scandi couch.

I was storing everything in my bedroom for the rest of the month. Experimenting with the ways I interacted with them even prior to picking up the keys.

So that by the time I arrived here, there was not a moment it could not have been ‘mine’.

*

If furniture is the backdrop to our lives then we must consider it a sort of ‘stage set’ – and it must predict the moves we make, and the pace at which we make them. The set we curate must hold a great deal of power in the way it is able to formulate the shapes which our bodies make around it.

My ma-ma (my paternal grandmother) orchestrates the rearrangement of her furniture almost every week. She’ll ask her piano students’ parents inside to help her. Then they will together, at her precise instruction, move her grand piano across the room and re-decorate around where it had once been. She’ll request for them to help her in replacing the new empty space with her five-seater couch – not her three-seater – or one of her four armchairs. The grand piano is now in the opposite corner.

I wonder what this says about her movements, her inclinations.

It’s not that she keeps buying or replacing furniture, in fact, she had had a shipping container import her entire set of bulky antique Qing-style pieces when she moved here and she’s kept them ever since. It’s just that she has found over 100 ways to fit these pieces inside the corners of her house. To change what you look at, which corners you face, which corners you inhabit, which corners you disregard.

*

In the month before moving in, my spare moments of thought were reserved for diagramming where my hypothetical couch would be placed in the apartment. Considering where the sun would set and which of the two rooms would be the bedroom, the other an office.

How does the sun rise on a horizon you are able to see from five-stories up, facing the north, the balcony toward the west? How orange is the sky here, which colour goes best with it.

During this time I was also supposed to be working on my second novel. In the novel I write about how the curvature of pots and kitchen items overly fascinate a retail sales-assistant. I became very close with this character during December, as J and I struggled to look for couches, and I started to understand how the arch of the back cushion affects the mood you are in as you sit in it. How to buy a couch that symbolises your absolute, cool nonchalance; one which you are able to just sprawl yourself across as you enter from the front door. But which also allows you to be propped up amply, at an appropriate height as you have a conversation with the person standing beside it. How to buy a shared couch for somebody who is 6’0 and somebody who is 5’1.

I realised, in thinking of all these things for the first time that I’d become interested with this idea that everything designed, everything made for us to feel as though we are ‘home’, perhaps wasn’t really made for us. There was no object that we could buy that would ever fully ‘understand’ us, that would fully form itself around us – though they are sold this way. We have to form ourselves around them.

When I was younger I was under the impression that houses ‘just happened’; I didn’t think about whether the large bed I would sometimes knock my shins on was made by someone who might’ve found it very convenient for themselves, perhaps it was created just to be beautiful, to stand out in a warehouse full of other bed frames.

Living in a settler-colonial country and a suburban environment my entire life, I’m accustomed to the idea that the big dream is to knock down, to rebuild larger, to build up or build back, to customise – and perhaps for this very reason of mass-produced impersonality.

But if you can’t afford to buy land or buy at all, there’s a drastic limitation to the possibilities. In a culture that champions land and the home-renovation-thing, to be in any other position makes the process all the more claustrophobic — often including more surveillance of your mannerisms, of your choices. The thing about living in the flat of a building designed to be leased or to house temporarily, (which I’d experienced a few times before with my family) is its strictness to unchangeability. How eventually the apartment will be asked to return to its original form for the next tenants. The walls need to remain white and without drillings or holes, the carpet needs to remain the same colour, it would eventually go out of fashion. And how all of this, right down to the material the kitchen bench was sculpted out of, can tell you which era the apartment was built in. This makes me think of colonial agriculture – how the more colonisers attempt to fit what had once been ‘home’, into a place which is not naturally ‘home’, into soil or atmospheres they do not understand, the more they frustrate themselves when they realise that the crops they want to grow, the structures they want to build, animals they want to mass-produce are not meant for this type of earth. And that their attempts at enforcing themselves and their ways of life into a place they have not yet understood, is actually contributing to its collapse.

Having grown up a settler on stolen land, moving out into my first home, perhaps I’ve grown accustomed to this way of ‘occupying’, in feeling entitled to beautiful things, to the absolute-most practical things.

The way we have been asked to exist in suburbia sometimes feels like a casing has formed around us, suburbia sometimes feels like pausing. Whether this design is deliberate or not, it can often promote stagnancy. It is a planet within a state, and it promotes occupancy.

We find ways for the things we want to grow to grow where we want, and if we are not able to do this, we must infiltrate another space to do so. We encourage import and export culture – we buy up land overseas to house production. You have to protect this type of ‘occupying’ with law enforcement and with conditioning that this is the way we absolutely must live.

Even moving around and relocating – if not romanticised as career move or celebrated as a thing money can afford – is looked down upon. The sort of ownership, settling and transplantation that we are taught to aspire to is not the way land, nature and its Indigenous cultures had intended. So when there are bushfires, droughts, floods, hurricanes – anything but the human flu – only then are we forced to move – and we are reminded that the things we keep around us are not for us to own, they’re not for us forever. We do not get the warranty, or a forever-guarantee if we want to control it.

*

To fit into the new space, I’m finding routines. I like the way I can carry the 1.7 litre kettle over just a little, so as to not hurt my forearm. Pour hot water into my shallow cup, where at the height at which I stand allows me to stare out the large windows, as I whisk matcha sediment into a paste. Opening these windows in the morning to let out the humidity that happens over night. Being on time, to sit on the balcony as the horizon simmers with a pink streak across it, the perfectly round, orange sun as it sets behind the group of buildings just a few suburbs over to the west – this is how it looks in the summer, at least.

These routines have very little to do with the aesthetic of the furniture or how I’ve curated the place, very little to do with these things actually being mine – it has to do with the fact of my changing, my growing. Perhaps the way we control the space around us is really not about control at all, it’s to do with the way we move around it, react to it, the subtle glimpses we catch of ourselves in it when we eventually see our habits too clearly. And when the space does become ‘stale’ I want to challenge myself when this happens, to reconfigure my lens of these objects being ‘old furniture’, despite appearing to be whole, conclusive pieces. Despite being knock-offs, imperfect, antique, second-hand, slightly broken. Instead I want to see these objects as artefacts of our highly specific, unique movements, in our temporary spaces.

And if we are housed, and able to quarantine – how can an unchanging environment around us motivate us to explore new states of mind, fed to us by the books we read, the films we see, the new physical, verbal and emotional languages we learn, the conversations we have, the walks we take – without us having to continue buying to re-define ourselves. How do we inform our spaces with our own changing without needing to force change? How do we support environments which are inevitably changing at the hands of us? To me there is both a hope and melancholia about how my mama moves her furniture around so often. Coming from two families of displaced people, many movements, cultural alienation, suffering and benefitting from colonial Hong Kong and Australia – her movement, her discomfort and her longing for change is habit.

Jamie Marina Lau

Gunk Baby by Jamie Marina Lau is out now!