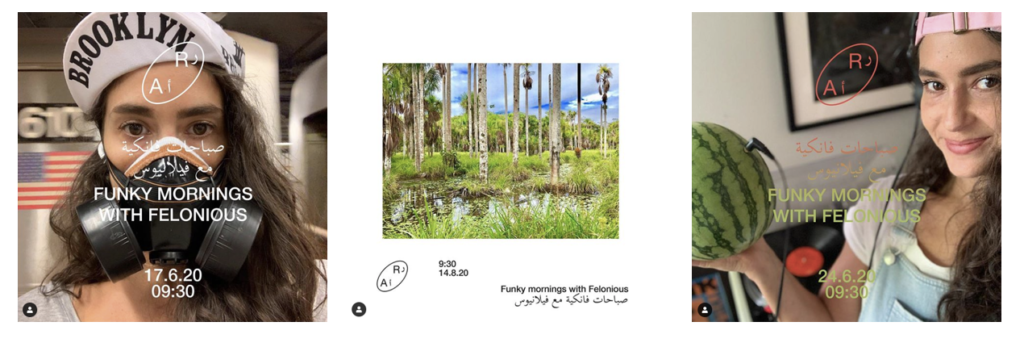

Out of the dozens of colourfully-named selectors which fill the daily programming of Palestinian internet radio station Radio Al-Hara, the one which caught my attention immediately was Felonious Funk. With a deliciously ludicrous nom de plume, her presence looms large, hosting her Funky Fresh Morning show twice weekly. When the 70-hour Fil Mishmish protest began on July 8th, she was the one to kick off proceedings and, after months with the station, some listeners now refer to her simply as The Funk. The funk is what her breezy, often tropical sets guarantee, a unifying mood which spans genres as wide as reggae, rap and disco; a traditional Yaminawá chant leads into some cocaine-disco from gaudy 80s outfit El Coco into deeply melodic rap with The Pimps Of Joytimes’s joyous “Janxta Funk!” “There’s a thread between them all” she tells me “and I like to find that thread”.

Yes, I did eventually speak at length to the mysterious Felonious Funk, and you can imagine my surprise when I discovered that this mainstay of a Palestinian pirate radio station was an international arbitration lawyer from Brooklyn. She says that both are vital to a satisfied mind; after years of leaning heavily into her right brain, the lockdown has finally given her the time to indulge her left. Born in America to Palestinian parents, she has lived between the US, London and Amman ever since. She fell deeply for African American music when she took up basketball and became immersed in its hip-hop indebted culture. Felonious has been DJing for only a few years, and is typical of the amateur charm of the station, where thrilling sets can just as easily slip into farce. During one mix Felonious’ needle stuck and she was raving too hard to notice; meanwhile listeners worldwide were treated to a minute or so of the sound of a helicopter passing by her apartment.

Felonious’ Brooklyn home is adorned with posters of Grace Jones, Miles Davis, her namesake Thelonious Monk, and a cat called Dexter. She joined Radio Al-Hara early, thanks to her friendship with two of its founders, Saeed and Mothanna, and it’s clear that her ethos suits a station which is unafraid to offer background music. When we spoke, Saeed joked about techno DJs approaching them with hardcore sets and he’d say “Come on, there’s no way you listen to this all the time”. A lack of intrusiveness is ironically key to Radio Al-Hara’s impact: their shows aren’t there to be studied; they offer music that seep into your daily life without great ceremony. Felonious echoes Alan Watt’s sentiment that “you don’t listen to music just to get to the end of a song”. The communality of simply experiencing new music gained Al-Hara it’s audience: “In times like this, it’s comforting” she tells me. “I mean at a minimum, it’s comforting”.

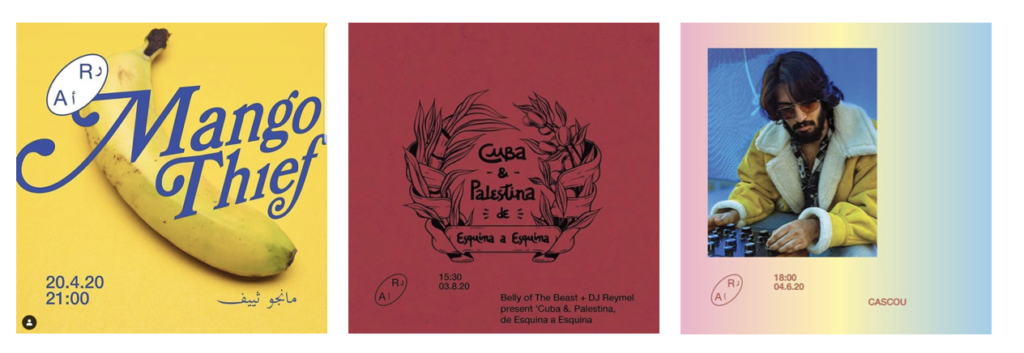

Felonious is one of a multitude of eccentric and colourful names to become icons on Radio Al-Hara. Another regular is her friend Mango Thief, an Amman-based collector whose first interest is in ancient African instrumentation, but will just as readily drop some Marcus Gad. There’s a presence from the classical tradition too in the form of pianist Dinah Shilleh, a composer from Ramallah whose show The Obsessives takes a narrative and technical approach to showcase contemporary composers from the Arab world.

For many of the selectors I speak to, their creative life is not only limited by Western imperialism but by cultural conservatism at home. Cascou, a DJ and curator of Radio Al-Hara’s Paradisea programme, is from Kuwait. “My country is quiet”, he tells me. “Pre-Covid there were several institutions like the Opera House that regularly had traditional Khaleeji concerts. Otherwise there’s no club scene here, period. Kuwait is a conservative and dry country. I don’t see an overnight transformation coming like our neighbours in the UAE and Saudi because of how tightly-knit the socio-political climate is here. You can’t even dance at these venues, it’s frowned upon”.

Countries divided by thousands of miles are united by experience. I spoke to Belly of The Beast from Cuba, a nation which has been, in effect, quarantined not only for the last few months, but the past six decades. Their media-project uses Cuban hip-hop as a means of covering the impact of US policies towards the island. In Palestine they saw a kinship, and so debuted a mix on Radio Al-Hara merging Cuban hip-hop with Arabic.

For Lebanese selectors, the situation is difficult in a brand new way. Ayla Hibri is a Lebanese photographer, painter and music selector living in Amman, and when I ask her about the music scene in Beirut she says, “Had you asked me this question thirteen days ago, I would have a different answer, but it’s so hard for me to answer this now knowing that Beirut is not the same after the horror that took place on August 4th. I don’t know what’s going to happen to the Lebanese music scene after this tragedy. It was thriving before the October revolution. Everybody knows that Beirut is the place to be when it comes to gigs and DJs and parties and it breaks my heart that things will have to be put on hold until we get back on our feet”. For these musicians, internet radio – a phenomenon which simply didn’t exist two decades ago – provides liberation when their physical situations offer the opposite.

It can be difficult to write about “community” and “creativity” because it all feels a bit “give peace a chance”; a hippy, liberal answer to very real geo-political problems. But another part of me feels that serious politicians try to ensure we feel that way, precisely because music as a means of liberation and community is actual, quantifiable, and far harder to stop than an economy. Playing two hours of other people’s music may sound like an odd form of individual expression, but that is to ignore the lifetime of listening which is being reduced to just that set of songs; as Hemingway understood, what’s included -matters, but what’s left out matters more. For Cascou “I never imagined I’d be playing recordings from my Dad’s reel-to-reel tapes from the 1980s to a listener in Recife, Brazil, on a Palestinian pirate station. Everything that’s great in the MENA musical landscape is converging into the beacon that is Radio Al-Hara and extending worldwide”.

Felonious Funk’s name came to her, unsurprisingly, while gazing at a poster for Thelonious Monk’s 1959 concert at New York’s iconic Town Hall. It became apparent that it’s more than just the man’s name which has informed her work though, so much so that she reads to me a beautiful quote from the vinyl pressing of his 1969 Monk’s Greatest Hits compilation: “Monk is a master painter of sound. He transcends bad pianos, noisy bars, saccharine tunes, uninspired rhythm sections and the passing of time. He is a transformer, turning whatever he likes into Thelonious Monk. His world remains a gentle, Sunday-morning world. It would be nice if the world were more like Monk… simple, spare, funny, together, childlike. Like a child, Monk is more complex than appears on the surface. Innocence is not simple, and simplicity is not easy…. Monk is neither dated nor contemporary, neither in nor out, because his strength is such that he need only and forever be Thelonious Monk”.

As the sound of Radio Al-Hara fills locked-down homes from Cuba to Kazakhstan, diligently soundtracking the lives of people in a dozen time-zones with music chosen by international selectors, it would be easy to denigrate breezy sets of tropical funk or Cuban rap as apolitical, or simple. But simplicity is not easy. The whole project has more than a little in common with Monk’s philosophy: it transcends a global pandemic, a dozen languages, authoritarian regimes and stuck needles. As with Thelonious, it’s nice to imagine a world more like Al-Hara; a gentle, funky fresh world.

Liam Inscoe-Jones

Next week: Responding to Lebanese tragedy, and the Fil Mishmish protest