Apricot trees are slow and temperamental: they reject the cold and, for their first five years, bear no fruit at all. “Fil Mishmish” is an Arabic expression which means “when apricots bloom”, and it was the name of Palestinian radio station Radio Al-Hara’s 72 hour protest against colonialism, racism, and a new era of West Bank annexation announced by Benjamin Netanyahu’s government in May. The message was simple: Palestine will be taken, when apricots bloom. While defiant, apricots blooming is noticeably more probable than the British equivalent: “when pigs fly”. The phrases were born of different worlds, and perhaps something is lost in translation, but it’s a fitting discrepancy: despite the resilience of the Palestinian people, their existence in the occupied territories is fragile, with the fate of a culture and people determined by the mood of a colonial power and its allies.

On the 17th May, Netanyahu was once again sworn in as Israel’s Prime Minister and quickly announced plans to annex sections of the West Bank, the Palestinian territory which was captured by Israel from Jordan in 1967 and has since been recognised by most governments (although only occasionally our own) as a military occupation. Annexation is recognised by international law to be illegal; Palestinian homes and businesses simply stolen from their rightful owners by force. The plan didn’t go ahead thanks to a spurious deal struck with the UAE – based on nothing by a promise – but the threat of annexation is just one part of the hostile environment forced upon the Palestinian population, whose protection they are legally responsible for. Apricots blooming seems even more unlikely for a Palestinian farmer say, when Israeli settlers have uprooted 2.5million fruit trees in the West Bank over the past two decades, cut off Palestinian farmers from the water supply and destroyed cisterns, pipes and wells to clear land for further expansion.

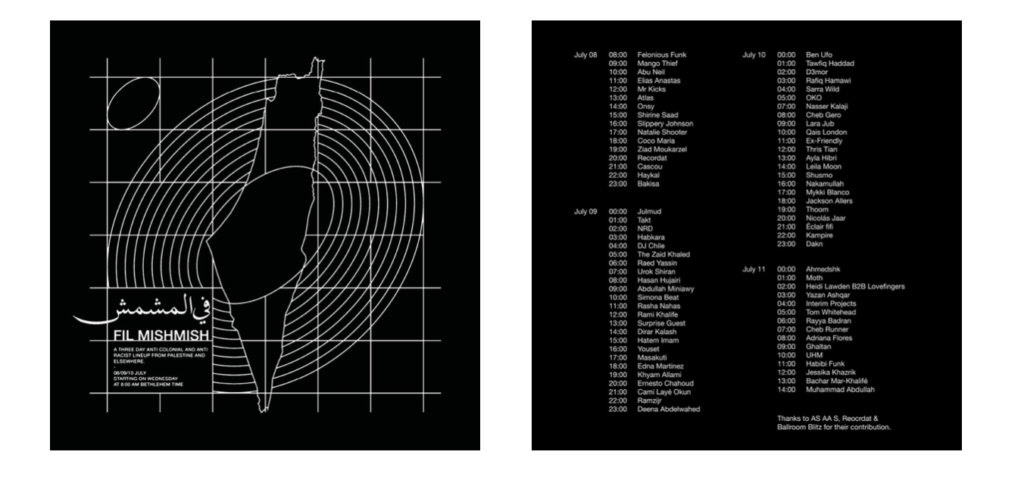

The threat of annexation was just the latest trial for Palestinians, who were already in pandemic lockdown and have being living under an aggressive police state for decades. International news simultaneously relayed footage of the murder of George Floyd and the global outrage at racial injustice which followed. The world was in turmoil, and it was into this that Fil Mishmish was launched. The protest played out live on Radio Al-Hara, on the 8th, 9th and 10th of July, with 72 sets streamed from musicians’ homes as wide as Nottingham, Lebanon, Mexico and the West Bank: a collective outcry against colonialism and racial injustice.

If that sounds heavy, Felonious Funk quickly assuaged any fears by opening the entire protest with a demonic remix of Mr. Roger’s “A Beautiful Day In The Neighbourhood”, smashed into Pharoahe Monch’s “Simon Says”. Radio Al-Hara’s usual appreciation for the tropical and funky did not suddenly take a back-seat to slam poetry: there was more cumbia than Phil Ochs, and diatribes were scant. Instead, selectors ranging from the completely amateur to icons like Nicolás Jaar simply shared their record collections as a balm for a common pain. Fil Mishmish was 72 glorious hours of funk, jazz and hip-hop, but it was also an international, grassroots protest.

Conspicuous was the degree of empathy exuded by people whose situations were themselves unenviable, with songs by Kamasi Washington, Terrace Martin and others spun in solidarity with African American protestors in cities across the US. It seemed reasonable to me that people already dealing with perpetual occupation could be excused for not speaking out about injustices unfolding on the other side of the world too, but on Al-Hara the opposite is true. T-shirts bearing the Fil Mishmish logo were later sold to raise money for the running of the station, but when the port of Beirut exploded on August 8th, all profits were diverted to the Lebanese Red Cross.

There is just a seven hour drive between Bethlehem and Beirut, and upon the day of the explosion the radio station fell silent for two days while its founders and selectors processed another regional tragedy. More than 50% of Lebanon’s population lives in poverty, half of their capital city was flattened by the August explosion and a government filled with ex-warlords and aristocrats did almost nothing in the wake of a disaster made inevitable by a toxic blend of corruption and incompetence. After four days of picking up glass and rubble off the street, Lebanese teenagers returned there to protest that same government and were met with their own military, wielding teargas and rubber bullets.

Hatem Imam is one of several Beirut-based selectors on Radio Al-Hara: he co-owns Studio Safar, a graphic design studio which was almost completely destroyed by the blast just ten days after his debut show. Upon his return to the station – a set broadcast from their new studio in co-owner Maya Moumné’s bedroom – the two selectors still found time to express solidarity with Gaza and the West Bank between songs. On Friday 30th August Radio Al-Hara debuted a second dedicated programme, 30 Hours for Beirut: a collaboration with shuttered Beirut nightclub Ballroom Blitz to help raise money for a Lebanese NGO trying to a save Beirut’s burgeoning creative scene in the wake of destruction.

Reciprocal solidarity was the essence of both 30 Hours for Beirut and Fil Mishmish. Relatively comfortable UK selectors playing international music alongside those in Latin America and the Middle East said more than days of guitar strumming, rally-crying “protest music” ever could have. From settler colonialism in Palestine, tragedy in Beirut, cultural conservatism in the UK, poverty and sanctions in Cuba and racial injustice in the US – we’re simply talking about lived experience of the age-old story of the powerful, and the rest. Starting from a Google Doc up, there is absolutely no doubt who Radio Al-Hara stands and jams with.

Liam Inscoe-Jones