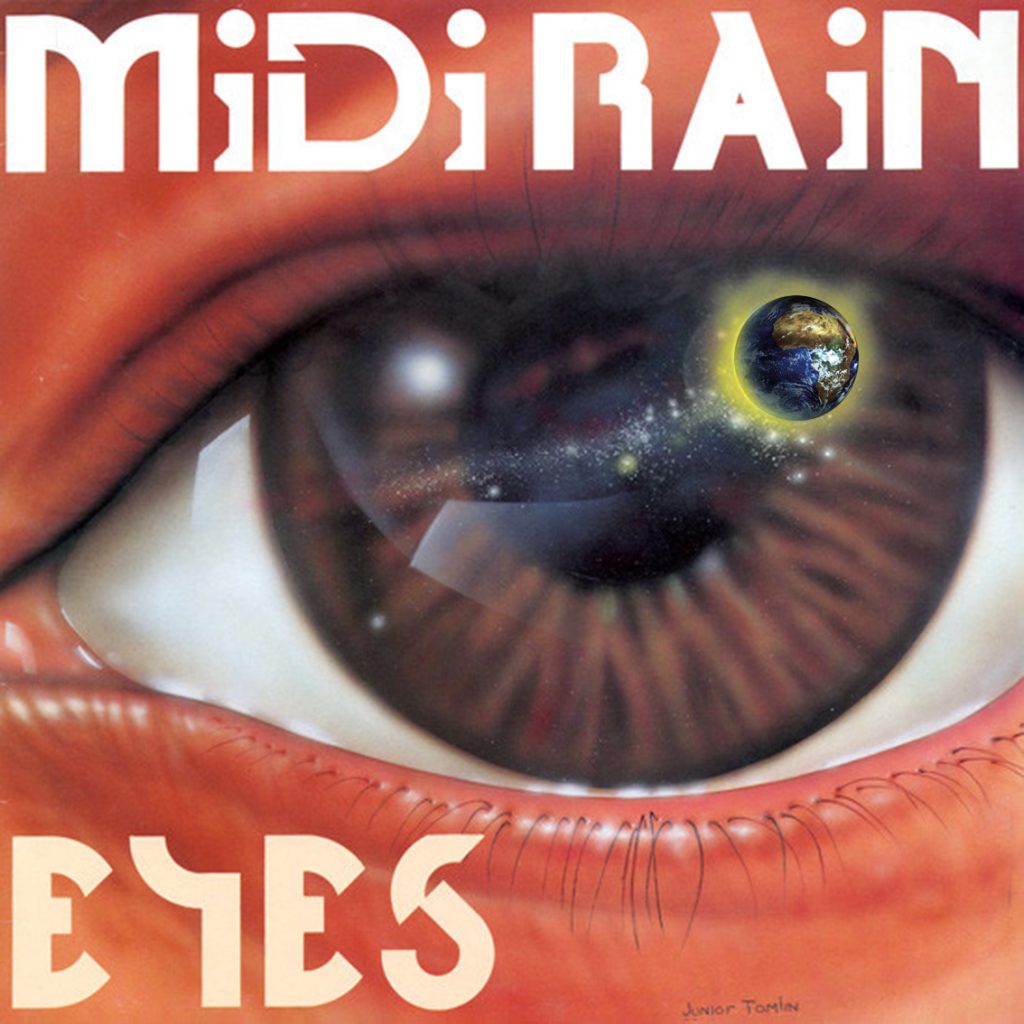

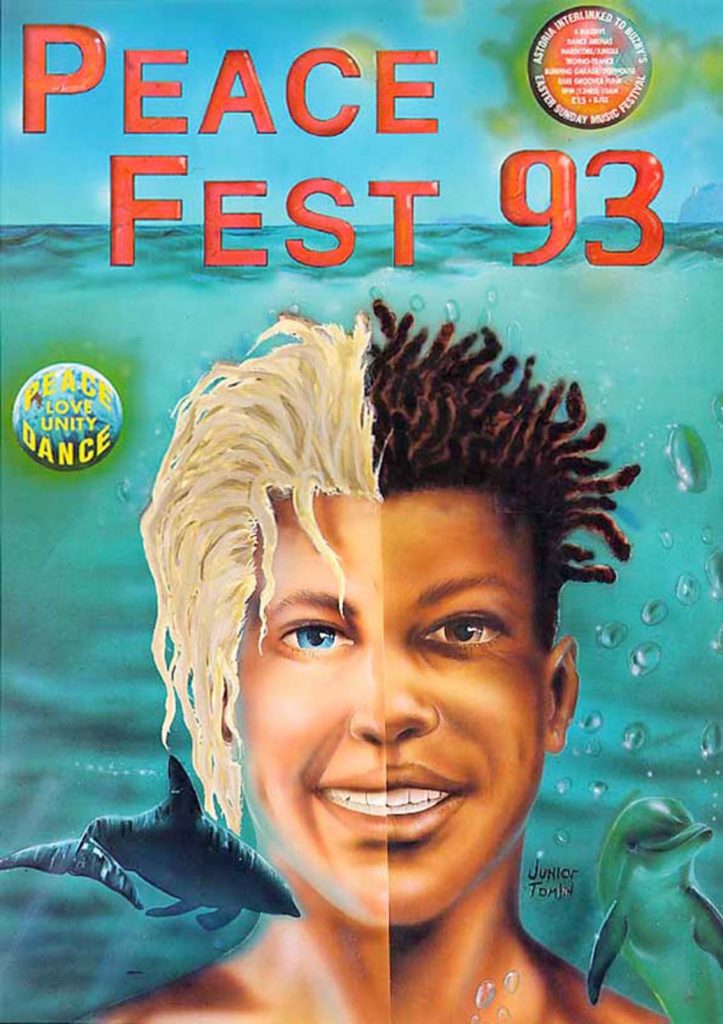

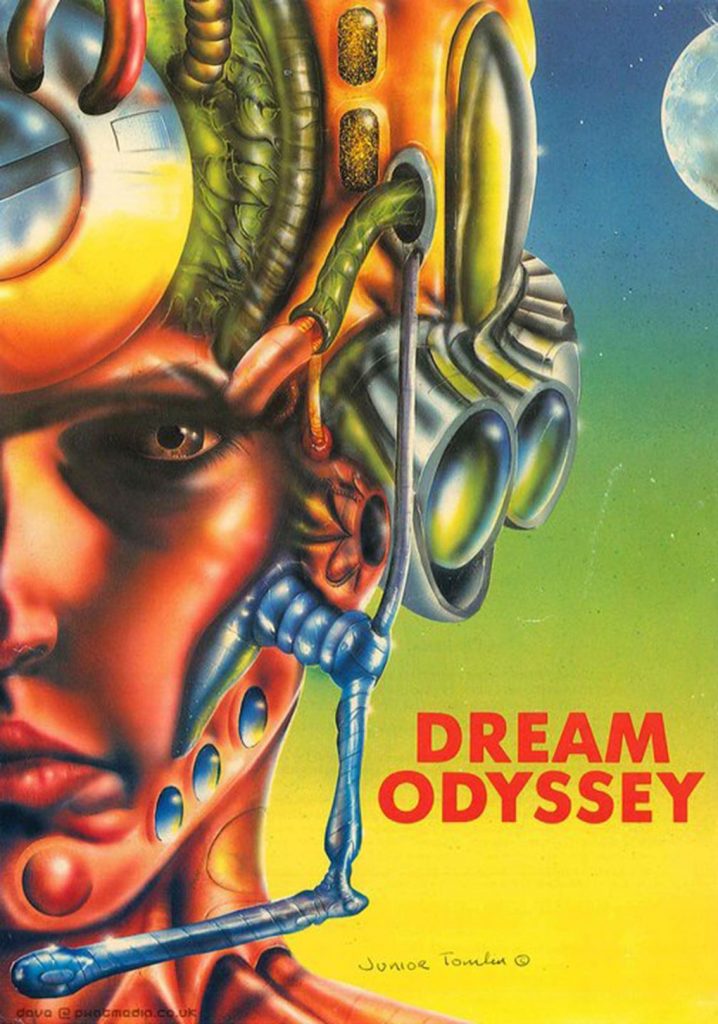

Today on The Social Gathering, we’re pleased to bring you an extract from an interview with artist Junior Tomlin. It’s taken from a new book – Junior Tomlin: Flyer & Cover Art – an amazing retrospective of his work in the ’80s and ’90s. Junior’s artwork was a vital and unmistakable part of the burgeoning rave scene, back when physical flyers were still king.

Huge thanks to Velocity Press and Marcus Barnes for allowing us to share.

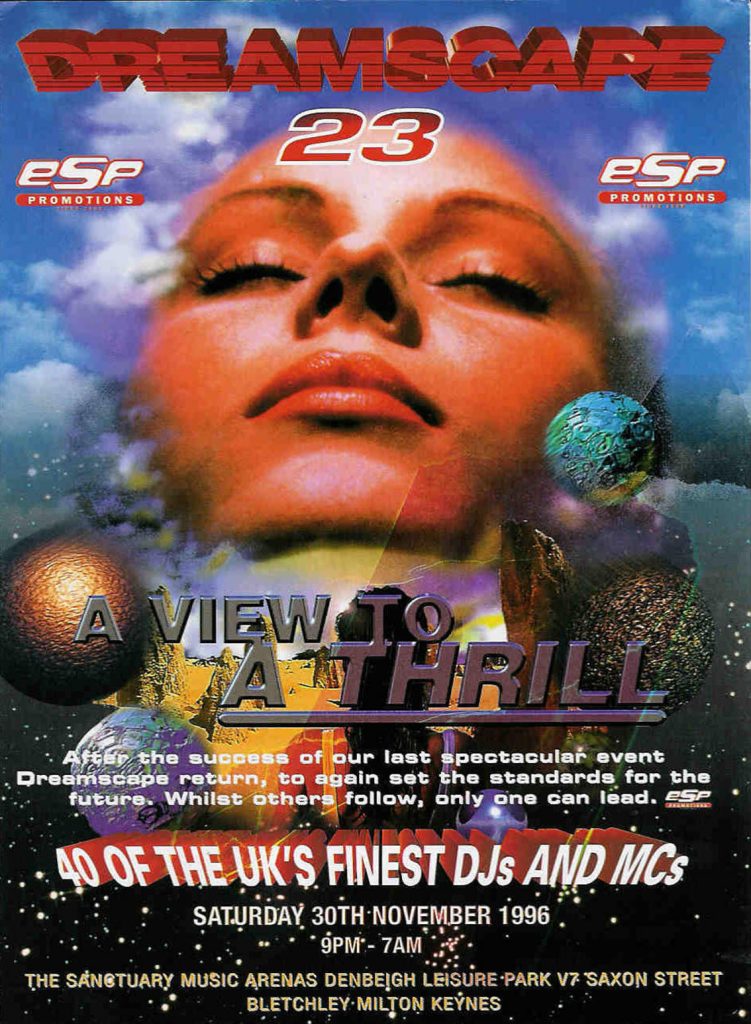

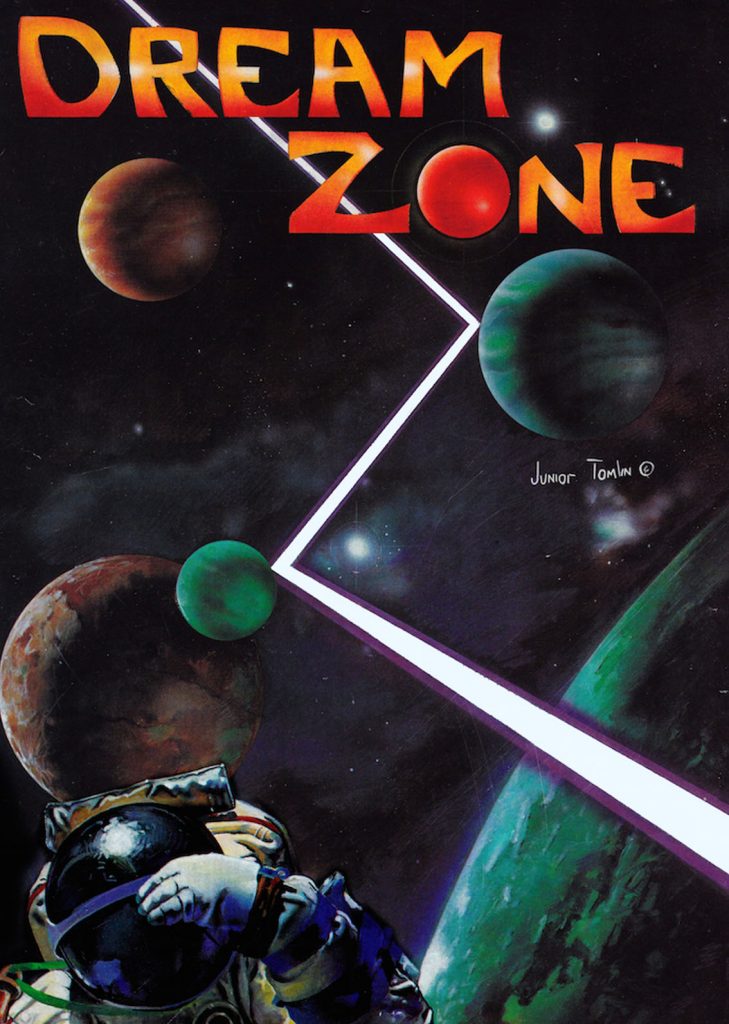

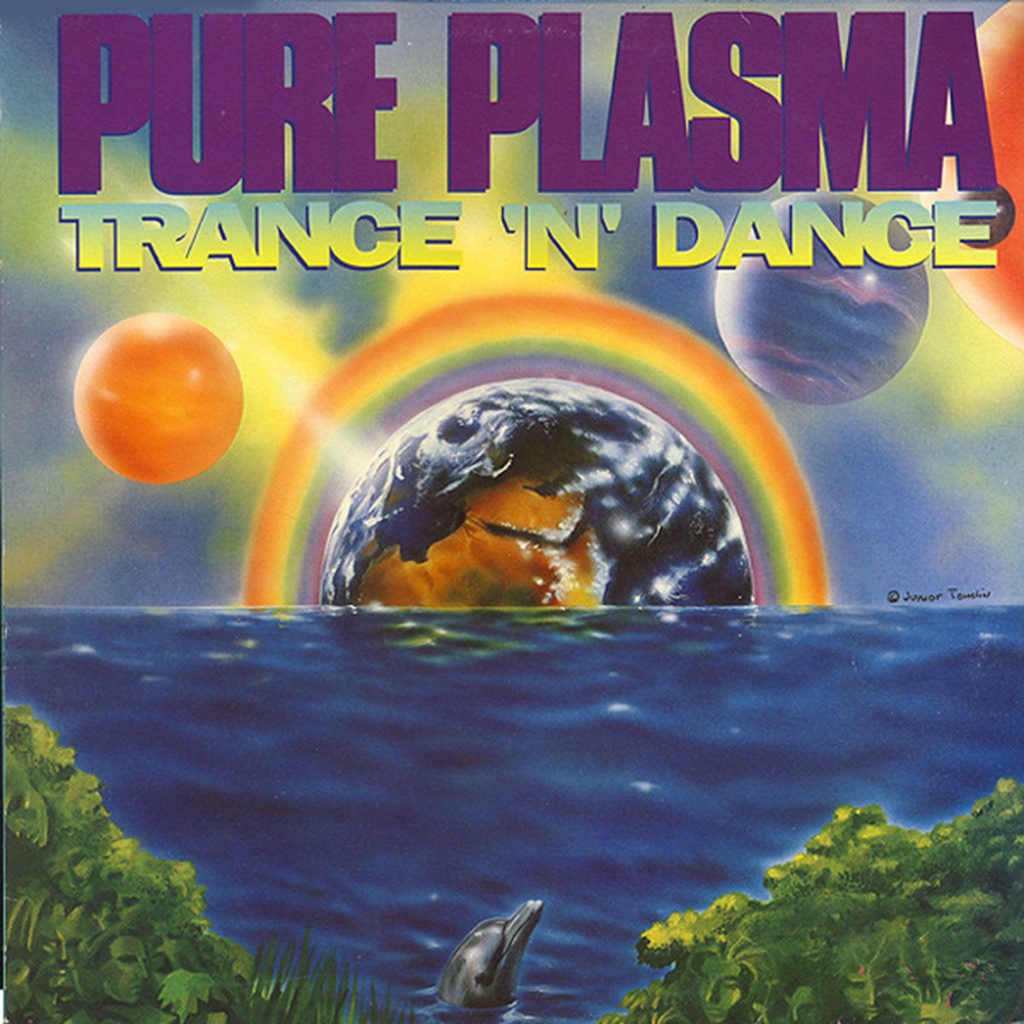

Born and raised in Ladbroke Grove, west London, Junior Tomlin’s life had humble beginnings and, despite his contribution to rave culture, has remained lowkey. As a child of the sixties, he was brought up on a TV diet of sci-fi and fantasy, TV shows and films that left an indelible impression on his young mind leading to his progression into the world of science-fiction inspired art. Over the years Junior’s iconic work has provided a visual identity for rave culture; surreal, futuristic and fantastical, just like the music, as well as working for the most influential comic book publishers in the world, Marvel. With his new book Junior Tomlin: Flyer & Cover Art out on June 5 we spoke to him about his journey so far…

Marcus Barnes

So, to begin with, can you tell me about your childhood. Where are your parents from? Where did you grow up?

My parents are from Jamaica, they were first-generation immigrants. I’ve been in Ladbroke Grove for most of my life. I grew up just down the road from the flat where I live now, and I’ve been in this flat for over 30 years, actually. My dad worked for British Rail as a shunter in the depots, and my mum was a cleaner. They knew I had a passion for drawing, but it was never really said. When I was about 11 or 12, my dad would point at me and say, “You’re going to be an architect”. He had a best friend who was an engineer, and whose wife was a teacher. They coached their son, and he was very bright, of course. We’d go to their parties every single year without fail, and that’s where my dad got that thing from, “You’re going to be an architect!” I think I disappointed him a bit when I said, “No, dad, I’m gonna be a printer!”. He didn’t like that.

When did the impetus to draw start to arise?

In our household, it wasn’t like we had tons of paper or tons of pencils… no. There was a lack of pencils, lack of paper. Somewhere in the house there was one particular purple pencil. I used it so much it got smaller and smaller and disappeared. Remember, it’s been 42 years since Star Wars. Around the time it came out I entered a competition where you had to draw your own version of a space battle. Star Wars really made you think forward in terms of technology, the future plus the fantasy aspect. I didn’t get anywhere, though. Space is supposed to be black, but I didn’t have enough black to fill out the page, so it was a load of spaceships on a white background!

How did you progress from not having anything to draw with to making it a hobby?

It’s called going to school. Doing art at school. I ended up drawing things for my friends, they’d come up to me and say, “Come on Junior you can draw; draw something in my book so I don’t have to draw it!”.

What happened after secondary school, did you go to art school?

I didn’t get enough grades to get to art school immediately, so I had to stay until the upper sixth. A Level Art was a two-year course. My art teachers all had my ranked me to get the highest mark, but guess what happened? The examiners killed me off and gave me an E.

What happened?

My coursework was very imaginative, and I think they marked me down because they couldn’t understand it. The life studies I did were fine, it was just the coursework. An E! It was a bit gutting.

What was your next step?

I got told that I’d need to do a foundation course and so I tried to get into a few colleges, but I got rejected by all of them. Then I applied to Byam Shaw School of Art to do a foundation with my mad portfolio of images that people couldn’t understand, and I got in. They were based in Notting Hill Gate, and I went there for one year.

How did you get on there?

I enjoyed it because it was a school for painters. I learned a lot of disciplines. I always say a foundation course is where you meet a lot of weird and wonderful people. That was exactly what you got. At school, you meet people who are of a similar mentality, but in college, you meet people from different walks of life with totally off the scale ideas and characters. It was the very end of the seventies going into the eighties, so a very fertile time for people forming their own ideas and identities.

Did you have any idea about what you wanted to do at this point?

No not really because after that course, I went on to study Graphic Design at Goldsmiths College. Back then we had ILEA, the Inner London Education Authority, Ken Livingstone was head of them for a while. Through them, I managed to get funding to cover all my studying for four years, grants as well, which you didn’t have to pay back. They gave you enough to cover your fees and a bit to live on. Then Margaret Thatcher came in and abolished ILEA. Before you knew it kids had to pay their own tuition fees. That’s where it all started to decline.

When did you get hold of an airbrush and start learning how to use that?

After I left Goldsmiths. I only had a college portfolio, so no one would take me seriously. I realised I’d fair better if I managed to get my work printed. Someone suggested trying my hand at computer game covers. I’d buy the magazines, and in the back they’d have job ads with contacts from the companies. I spent a lot of time calling them up and asking if I could go in and show them my portfolio. The first cover I did was called a game called Sun Star for a company called Computer Rentals Limited in 1987. It was a relatively simple brief: a picture of the sun, with a solar flare and the words’ Sun’ ‘Star’ over the top. It was a start though, and I’ve pretty much been freelance ever since. That went in my portfolio and led to a steady flow of more work. I had to work pretty hard to get jobs, phoning around and going to trade shows at Olympia and Earl’s Court, but it meant I could build up my portfolio. A good way to get work was to call up a company where the artwork wasn’t up to scratch, I felt bad because someone would obviously be out of a job because of me but if their work wasn’t up to much that wasn’t my fault.

Tell me about your connection to music then. You mentioned sneaking out to parties with your sisters but were you going to raves before you started designing flyers and record covers?

No, the work took me into the culture.

What were you listening to then?

I was into dub reggae. Instrumentals. When you’ve got things like jungle, drum & bass and dubstep, I always find that it’s like a science-fiction type of dub. I used to listen to John Peel’s show a lot, I got introduced to a lot of music through that show – Gang of Four, Joy Division, Ultravox, punk, everything. He was way ahead of his time. That programme and The Old Grey Whistle Test, I loved those.

How did you end up moving from computer games covers to record covers?

I can’t remember how, but I met Peter Harris, who owned Kickin’ Records. God rest his soul, he passed away in 2008. I told him I’m an artist and he gave me the responsibility of doing the cover of a record from his label. I jumped at the chance because it was fun, he was a good person to work for. That’s where I met the other proto-junglists at that time: DJ Hype, Grant Nelson, The Scientist and quite a few others. Their office was a 15-minute walk from where I lived. I worked from home mostly, but I’d pop up to the office regularly, sometimes just to say hello if I happened to be walking past. Peter would always tell me, “You’re underselling yourself”. It’s like he wanted bigger things for me, even though I couldn’t see it at the time.

What happened with the video games work?

It started to slow down a lot. The method they used to make the covers changed, they began to use screenshots on the boxes rather than original artwork. Things have a lifespan, and computer games came to an end. When nobody is calling you up to do work anymore, it’s time to find other places or industries. Mute Records was my first regular music client. I was a tutor at the London Cartoon Workshop down the road from where I lived. At the end of one of my classes a member of Renegade Soundwave came into the centre looking for an airbrush artist to do one of their covers. It was for The Phantom/Space Gladiator. Before me, it was Dave Little doing Renegade Soundwave’s artwork. Somehow they were directed to me. I ended doing three covers for them, after that, I started working for Kickin’. Then I went on to Vinyl Solution. It was Peter who connected me with the guys at Vinyl Solution.

By the time you were attached to the record labels, did you feel like that was where you wanted to be?

It was a stable cash flow, where I didn’t have to worry about not getting work because the labels were constantly releasing things. For a time, I was the main artist for a few of those labels. But freelancing is always up and down. Beat Farm lost their offices at one point and was only doing black and white artwork for a time, so you lose that one…

When did you make the transition from airbrush to digital?

That was around the time I was working at Slammin’ Vinyl, so the mid-nineties. I wasn’t getting my original artwork returned so I thought, “Sod this, I’ll do it digitally so I can send them the files and keep my artwork”. I didn’t have to worry about trying to get my work back. I taught myself how to use the software, no courses. You’re constantly learning on the job.

Were you listening to the music and going to the raves as well?

Yeah, I went to a few of the raves, and I was listening to the music, too. The lovely thing about visiting the record companies was that they’d give you a nice wad of vinyl whenever you popped in, white labels as well so you’d get a few surprises when you brought them home to have a listen.

Did that inspire your art as well?

It inspired me and reinforced what I thought of the music. In a way, we were doing similar things, both looking to the future and into science-fiction, fantasy and all of that.

How much of your work was given as a brief, and how much was your own ideas?

Initially, they gave me briefs, but after a while, most of the people I worked for just gave me the name of the track and let me loose. I did get some very funny ones though, like Wishdokta’s Banana Sausage, for example. I started thinking, “How am I gonna do this?”. Then, of course, I looked at the shape of them and thought, “I’ll put a sausage inside a banana!”. When I showed Peter, he was like, “Great! How much?”. I said, “£150”. He said, “What?! For a banana sausage!”.

It must have been a lot of fun doing all of that work.

Yeah, it was great. It was a good period of my life. I was sketching a lot, coming up with new ideas all the time. Things like taking a centaur, which is half man-half horse, and making a centaur biker. Exploring fusion a lot. You can take one element out of context and create something totally new. The lovely thing I do know is because I have such a massive backlog of stuff, I can mash up my own work. So you’ll see recurrent themes and characters in what I do, but there will always be a new twist or evolution. I repurpose my own artwork, take something from 20 years ago and bring it forward. That’s the wonderful thing about working with digital imagery – you can take things, copy and manipulate them, and make something new from them.

Did you feel like you were part of something?

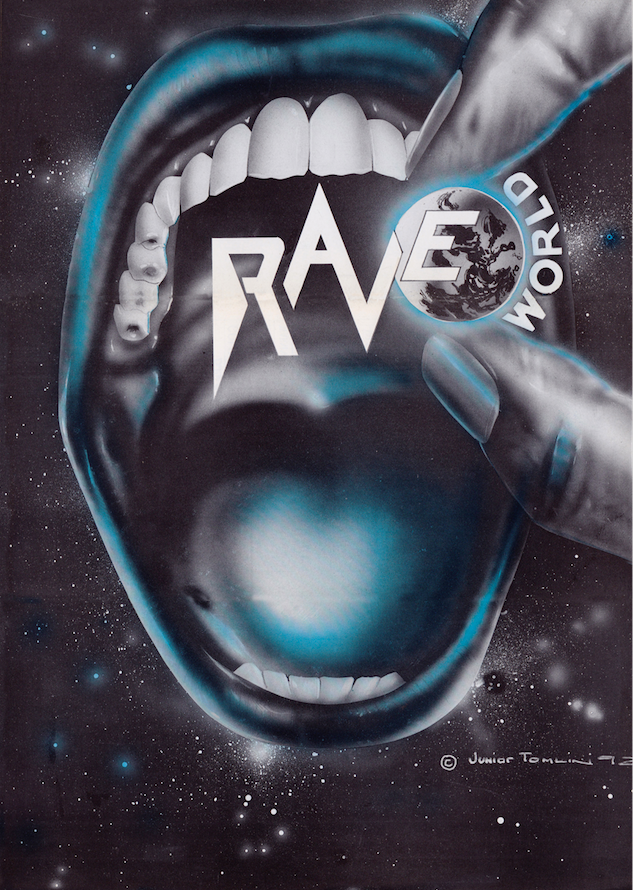

It’s funny, yeah, you feel like you’ve been there since the beginning. The first record cover I did was in 1989 and the first rave I did was 1992 – Raveworld with the three heads floating in space. I enjoyed the rave era, it was so new. Especially when you’re listening to the music and also listening to it evolve, from the bleeps to the hardcore to the jungle and drum & bass, it kept on evolving. I was tuning in to pirate radio stations, when I could actually pick them up, buying the records, listening to the records. I’d hear something on the radio and try to track it down. I used to go down to Mash Records on Oxford Street just to find my flyers because sometimes the promoters would forget to get me copies. I was down there one day, and I met Ray from Rugged Vinyl, which is how I ended up working for them. Everything is interconnected.

Were you aware that people were collecting your flyers?

No, I had no idea. I only found about that years and years later. You hear about a website that has sprung up or eBay where people are selling your flyers.

How do you think of yourself now, looking back over all the work you’ve done?

It’s a little bit overwhelming, there was never much of a chance to sit down and think about the part you played. It’s only when other people tell you the impact that you had on their life, and then it dawns on you how much you did for other people. Yet, you’re still hidden away behind-the-scenes.

So you’re 60 this year and still creating. What’s your vision for where you want to go next?

I’d love to have more exhibitions. I’m always striving for a bit more recognition, places like the Tate and the V&A would be my dream. My work is part of social history, there’s time and feeling connected to it. Everyone out there knows about it, people from our generation at least. I’d like to teach some of this stuff in schools, teach art, awaken people and get creativity out of people. Get the geeks out there!

When all is said and done, how would you like people to remember you as an artist?

As a person who is always living through the future.

Pre-order Junior’s book by 5 June to get a signed copy