Outside the back door a thin layer of snow has started to settle on the old stonework and the wooden decking. The mulch I’d put down on the borders a week ago is covered in what looks like a delicate lattice of white flakes. I can see my breath on the air as I walk round the garden finishing off a few bits and pieces of preparation – putting out blankets, checking the heaters all work, taping the laminate QR codes onto the pub’s picnic tables. My hands are reluctant to their tasks, frigid in the cold. What better, more auspicious start to the day than this snap of weather, I think to myself. Surely this is nothing if not perfect for a day in the pub garden – bitter cold winds, a dusting of snow, steel-grey skies above the line of hills. Of course the gods were not going to grant any of us the mercy of a fine day for the pub’s re-opening. It is, I thought, the final affirmation of their messages of the last year. We have given up on you, you are to live out the rest of your days alone with your mistakes. With your plastic and your leached soils, with your corpulent wealth and your meaningless technologies.

Despite the conditions we are due a full house all day. Since the announcement a few weeks ago of the government’s ‘roadmap’ out of this last lockdown, the phone, along with our three voices in answer, the up-lilted, false brightness of our stock replies, has been a kind of melody line running over the top of the days’ interminable silences. Bookings are made, explanations of the rules, of the menu, opening times. A sort of check list for people who sometimes appear to have forgotten how all this once worked. And why should they not have, after all. We have had our re-openings last year, the summer and into the autumn, but the truth is it feels like a year of de-socialization, of forgetting ourselves. And this last period the worst of the lot, the dark, grim little days of the year’s end. A hard northern European payback for the aspirational mediterraneanism of last summer’s high days. Then Christmas a no-show, none of that strange melancholy celebration of the new year. Just the bastard days of winter, hanging on even now into the spring.

One of the old boys on the allotment, who everybody calls Pete the Henhouse, says when he talks of gardening, that winter’s no time for the old or the green, and I thought of his phrase many times over the previous week when the news broke about the death of Prince Philip and the country seemed to descend into a kind of symbolistic mania. Perhaps it is not quite true to say the gods have become miserly in their offerings, for here we were given one of the very highest quality. In the midst of a national disaster, one that has claimed thousands of lives, and quite possibly the collective senses of the nation, here we had a prominent old warrior-king to bury. The grand old duke with his grand old jokes, his final flourish a Land Rover (built in the Tolkienian heartland at the very centre of the country of course) customised as a hearse. Why not throw the body on a pyre of Barbour jackets and corgis, send it out to sea, from the white cliffs, on a scale model of the Victory, launch it into space powered by the hot air of ‘old-fashioned jokes’, post-War bluster and a barely concealed contempt for the people. We heard for a solid day or more, in an endless euphemism-loop, exactly to what depths our national broadcaster and our increasingly creeping media class will go in order to obfuscate the hard truths of a very real, and thus truly flawed human life. By the end of the news cycle this was a man, as far as I could gather, of unflinching moral bravery with the work ethic of a gladdened Sisyphus, an underdog hero, last of the straight-talkers, seemingly the ur-text of husbandry, an ecological revolutionary and tireless champion good causes. The desperate clinging on to old certainties of class and status via the degradation of language felt at times like an appropriate final act to what has started to feel like an age that has given up reason in order to placate the simplicity of a hierarchy of symbols. It is true that this was a man’s death and so, of course, as profound as any. But what did it mean, I thought to myself all week, to hear of the death of ‘a husband’ and ‘a father’. How did those words attach themselves to this man as they did to my own, or to me? We shared almost nothing in common and as far as I could read, between the lines of puffery, here was somebody who would have met me with an open contempt, though written up, undoubtedly, as merely a ‘no-nonsense impatience for fools’. My own fault, somehow, for not being quite the right sort. Of course I’d known that sense, had felt it at school and in any number of interactions over the bar over the years. There were still enough seriously old families about the village that got in the pub now and again to remind you, however dimly felt, of your place.

The people take these offerings as they find them, though, and activate the old myths, dust off the medals and the bugle, indulge the solemnity of the moment. And perhaps that’s as it should be too, for is there not something of the same sentiment and backward-looking ritual about my last walk round the garden this morning, putting out the beer mats and the ashtrays, and finally, most pleasingly, turning on the ale in the cellar. Is there not something of our old selves about all the things I have missed about this place? Is it not implicated in its own petty hierarchies and so mimetic of those that are such a pernicious influence on our politics and lives? I pour a small libation for the departed, the first drop out of a new barrel, brown beer on the middle-England ground for the death of a culture, for the last gasps of a broken state. I shake myself out of my rather depressed countenance. The first punters will be here in a matter of minutes. I pour another, full, glass out of the new barrel, take the top off it and swallow. It really is very, very good. For all our faults, I think to myself, and they are as fathomless as we are, we’ll always have our beer.

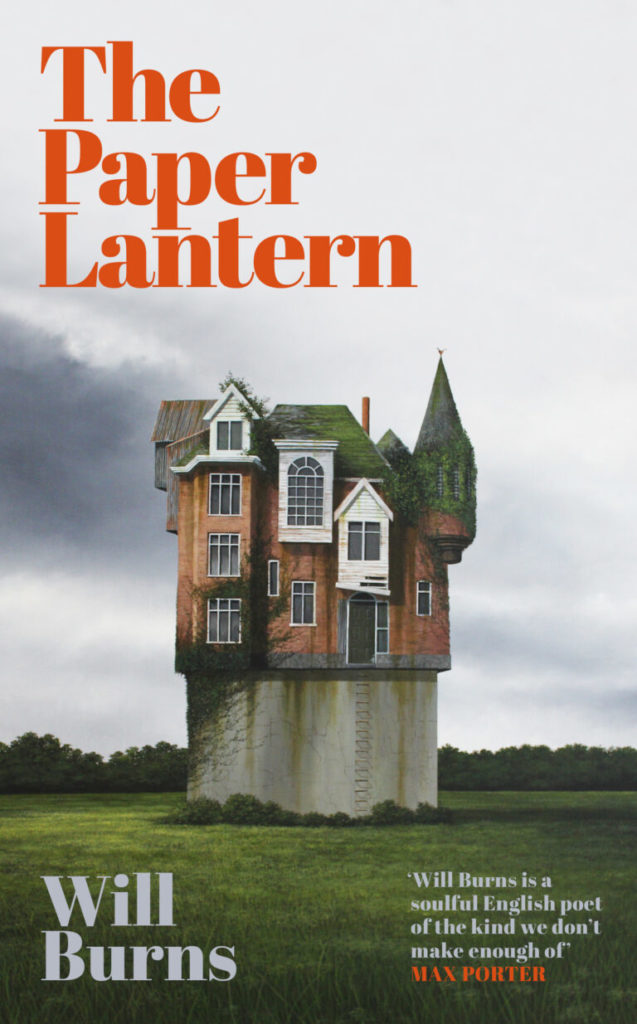

Will Burns

Preorder The Paper Lantern now