I felt a huge responsibility writing this book. It felt like this was the one chance in a generation that such a volume was going to be commissioned by a mainstream publisher, and the story needed to be told as exhaustively as possible.

The years I spent researching and writing it were probably the most sustained and intensive of my career so far. Many times I got silted up with facts and became stuck in the reeds. Other moments were ecstatic, when you could sense the connections and serendipities almost finding themselves, lighting up like synapses across the expanse of time and music. Like the discovery that the original designer of British pylons, Sir Reginald Blomfield, was also an acclaimed horticulturalist who wrote books on the English garden. Or that Terry Cox of arcadian-folk-rockers Pentangle played drums on David Bowie’s sci-fi hit ‘Space Oddity’.

Finishing the manuscript felt like exiting an enchanted land I had been wandering in for years, and after a few months of promotion came to an end in the autumn of 2010, I was slammed by a mysterious illness that drained whatever energy I had left. After two weeks in intensive care – looked after by the amazing staff of Kingston Hospital – I came out twenty kilos lighter.

As someone who had never spent much time thinking about my national status, I ended up feeling more grounded in the triple identity as English/British/European. The separation between the culture of Britain (which I can feel patriotic about), and the many iniquities of the British state, became clearer. Electric Eden is a love letter to British creativity, resourcefulness and revolutionary underbelly, but that’s not the same as a paean to nationalism.

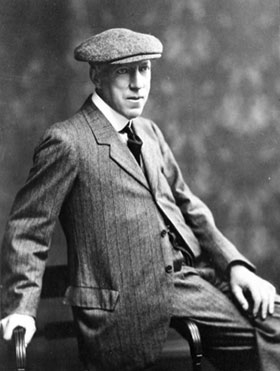

Finally I think I reached an understanding of the whole vexed question of authenticity and the folk process. Cecil Sharp, one of the original folk song collectors, compared folk to an oak tree producing an acorn – each time a folk song is sung, it’s like a new sprout from the same stem. I continue to believe that folk, or indeed any music, quickly loses its energy and becomes stagnant when it draws too much upon itself, and insists on a right way and wrong way of doing things. The most exciting music in the book admired what had gone before but passionately wished to make it new. That is the way we move forward.

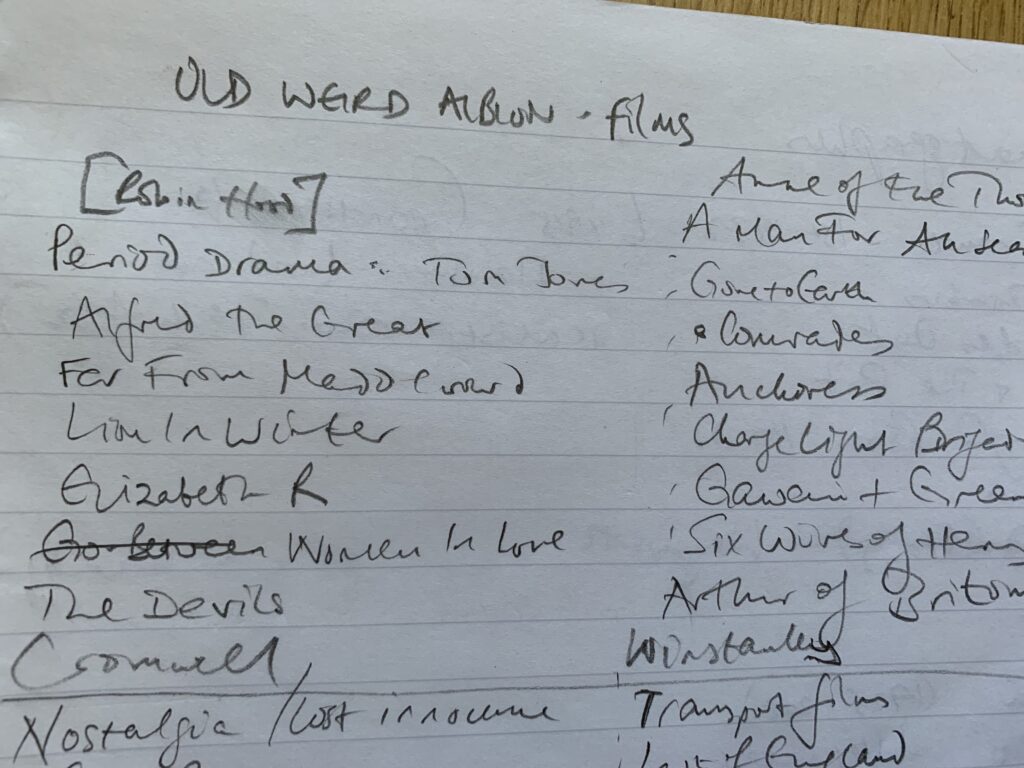

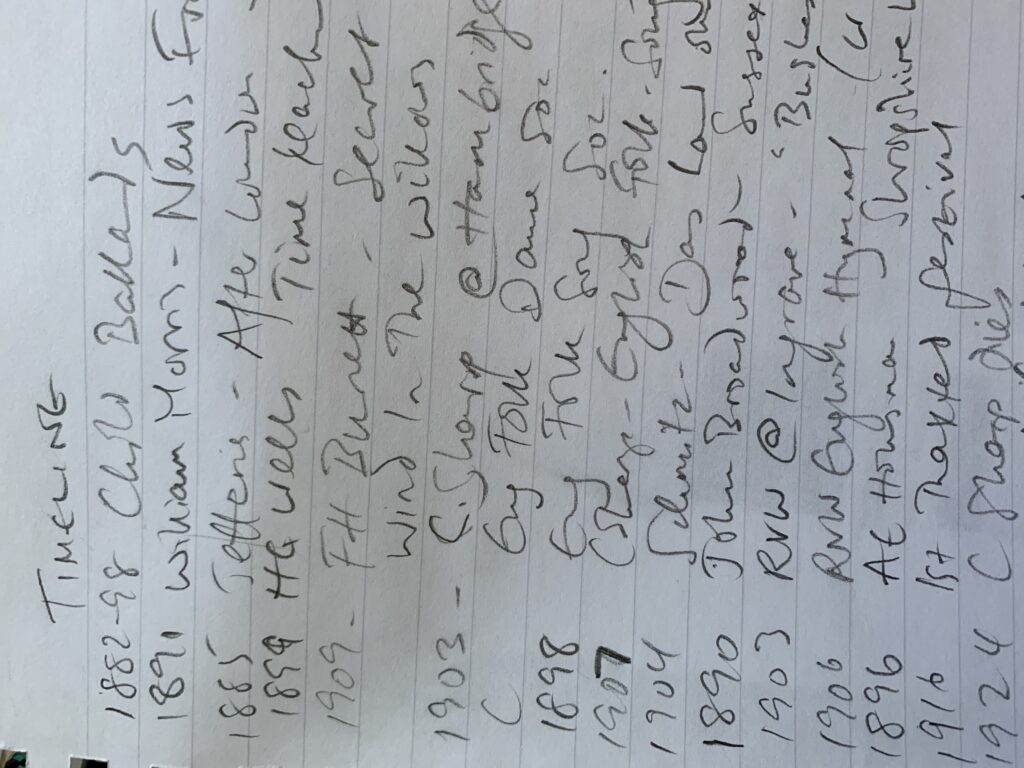

By the end, I also realised that there was a whole other book to be written. Along the way I littered the text with references to books, poems, films and television programmes that seemed part of the story – like The Wicker Man, Penda’s Fen and even Bagpuss. In the month the book came out, I wrote a feature for Sight & Sound headlined ‘Films of the Old, Weird Britain’. That was the germ of a book that will finally see the daylight in 2021, called The Magic Box: Britain Through the Rectangular Window. In many respects it’s the Electric Eden guide to British film and TV.

Rob Young