The more perceptive among you might have noticed we missed a few entries into the Social Library. Well for one reason or another we got a bit behind, many apologies. But we’re back with a fantastic review and recommendation from Matt Thorne, introducing the June Social Library entry, Got to Be Something Here: The Rise of the Minneapolis Sound by Andrea Swensson.

Since Prince’s death in 2016, there have been an enormous number of new books about the artist, with volumes by ex-bandmates or fellow musicians like Morris Day and Mark Brown, his ex-wife Mayte Garcia and long-time collaborator Sheila E, ex-manager Owen Husney, ex-bodyguard Wally Safford, and even his hairstylist Kim Berry (who wins the award for best title with Diamonds and Curlz).

Many of these books present differing or conflicting versions of the artist. Critics like to seize on this to suggest we will never get close to ‘the real Prince’, whatever that means but the truth is, the real Prince is in almost all of these books. He presented different personalities to different people, like most of us do, but on a much larger scale because he played different roles in so many different people’s lives. Some versions of Prince (such as the one revealed by Dan Piepenbring in his account of working with Prince on his sadly unfinished autobiography, The Beautiful Ones) fit exactly with the picture I’d built up of him after seven years of close study. Others, such as the nutcase who runs amok in Neal Karlan’s This Thing Called Life, moaning about his guilded cage and writing a one-off “blues for fighters” on “slow guitar, soft trumpet, and a bell” to deposit on Sonny Liston’s gravestone, feel more like invention.

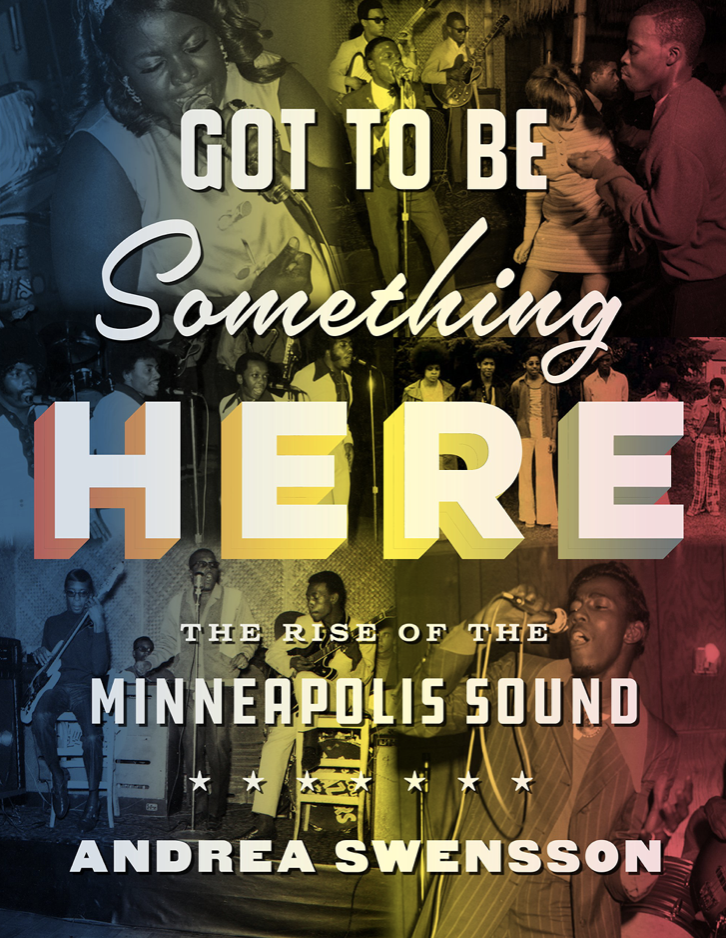

The Minneapolis-based author, radio host and music journalist Andrea Swensson, whose book Got to Be Something Here: The Rise of the Minneapolis Sound has just been published in a new paperback version, is particularly alert to a part of Prince’s story that some critics, such as the gifted poet and critic Scott Woods, author of Prince and the Little Weird Black Boy Gods, have suggested is underrepresented in the canon of books about Prince: the pre-history of what has come to be known as the “Minneapolis Sound’.

For Woods, too many critics ignore Prince’s pre-fame history in favour of comparing him to big (and usually white) rock names. Part of the reason for this is that, at least while he was alive, fellow musicians were reluctant to trade on Prince’s name or reputation. Their stories might have been part of his story (or vice versa), but if telling their tales meant they would anger him, they stayed mum.

This isn’t the only reason why the historical record is incomplete. Swensson also believes that voices have been silenced by “the overwhelming whiteness of our historical narratives”. Her focus for this book is, then, the twenty years between Bob Dylan leaving Minnesota in 1961 and Prince’s appearance in the First Avenue Mainroom on March 9th, 1981—though her true starting point is 1958 when the first R&B band from Minnesota, the Big Ms, recorded their first single. She isn’t the first person studying Prince to dig deep into the past, as the famously thorough authors of The Vault began their coverage of Prince in 1680 with French explorer Father Louis Hennepin discovering St. Anthony Falls, but as a denizen of the city she has a geographical advantage to many writing on Prince and brilliantly draws on local detail.

Swensson tells the story of the Minneapolis Sound by focusing on locations: the racial divide during times of segregation between the North and South sides of the city; the school integration system where North Minneapolis kids were bussed to the south side; the importance of clubs like King Solomon’s Mines (the first downtown Minneapolis club to host black musicians and cater to a black clientele) and the Blue Note where “every black musician got their start” and community centres such as The Way on Plymouth Avenue where all the main players credited with the creation of the Minneapolis Sound—Prince, Morris Day, André Cymone, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis first got together to jam.

While Swensson’s aim is, in part, to get away from the automatic association of the Minneapolis sound and music scene with Prince alone (at least until the final few chapters of the book), she also acknowledges that it wasn’t just Prince but also his relations who played a part in developing the city’s music scene. Swensson is intrigued by the way the relations of Prince’s generation of musicians worked together before their sons and nephews did, pointing out that before Prince played with André Anderson in his first band Grand Central, André Anderson’s father Fred played bass in John Nelson’s jazz trio while Prince’s uncle Maurice Turner jammed with Jimmy Jam’s father James “Cornbread” Harris, Jr in the Augie Garcia Quintet.

According to Swensson, prior to Prince’s Revolution, there’s a long tradition in the city of black, white and Latino musicians working together in bands dating back to the 1950s. Anyone intrigued by why Prince was so interested in working with Bonnie Raitt in the 1980s will find (part of) the answer in a section on how Raitt recorded her debut with interracial Minneapolis band Willie and the Bumblebees. This band would later favour Studio 80, the space famous to Bob Dylan fans for being where he recorded the inferior revisions of Blood on the Tracks songs and to Prince fans for the much-loved 1977 sessions recorded there prior to For You.

Working as a music journalist for Minneapolis’s The Current, Swensson would cover Prince’s hometown shows and interview ex-band members. After inviting Bobby Z onto the show, Prince summoned Swensson to Paisley Park to caution her against nostalgia. Famously resistant to exploring his past, Prince wanted her to focus on his latest records. Swensson tried to bypass this by asking him about the very early days of his career, which she covers in detail in the final few chapters of this book, drawing on interviews with André Cymone and Sonny T(hompson). Slightly more amenable to this, Prince nevertheless clearly saw an unbridgeable psychological divide between where he was then and where he’d been back then, even if geographically he was still in the same city. Prince’s connection with Minneapolis is sometimes overstated: he did live in other places (Toronto, Spain, and Los Angeles, among others) and spent much of his life in the air or on the road. But he did keep coming back home. Why? The answer is in Swensson’s title.

Matt Thorne

Available now from Waterstones for only a tenner in hardback!