It’s All Sensations – Bessie Smith by Jackie Kay. Reviewed By Will Burns

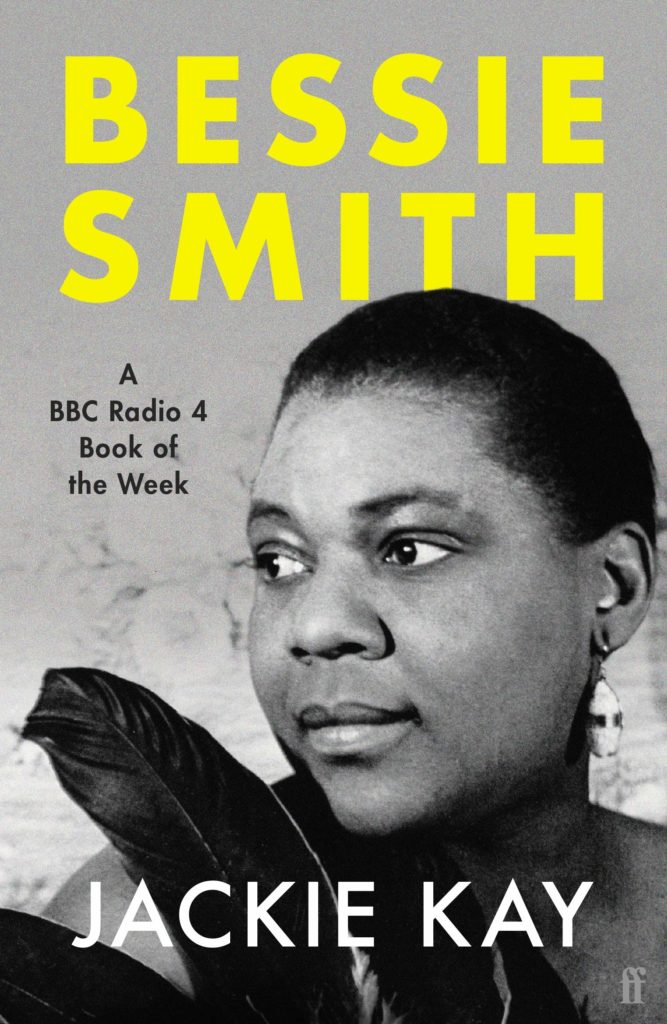

How do we come to our musical heroes and heroines? How do we find them, those figures from our own young and emergent tastes, and through that finding start to build ourselves? Jackie Kay’s book on Bessie Smith, originally published in 1997 and now re-printed by Faber, begins somewhere approximate to those questions. Namely, a ‘suburban street in the north of Glasgow’. Kay is adopted, she ‘never saw another black person’, and so, she tells us, when she discovered the music of Bessie Smith, it felt ‘like finding a friend’. Of course the discovery of such a monumental figure in American music allows for Kay to lift-off from autobiography into the stew of American history and culture in the early twentieth century, but the success of this book is just how deftly, just how originally, that lift-off is handled.

People and places are the heart of the story. Kay traces the names of places through song titles, establishes a kind of blues map of America in her imagination. And then there are the characters in the songs. The dying people, the wild women, the unfaithful, unreliable, unlikeable men. There is that revelation that comes with early immersion into folk forms – where are the boundaries between the singer and the song? The blues, folk, early country music all rely on a tight bounding-up of artifice and autobiography, a blurring of lines. And to Kay, that comes with realisations of her own about herself and her surroundings. ‘The shock of not being like everyone else; the shock of my own reflection came with the blues’, she writes. These moments in the book are in a kind of play with elements of broader social analysis, reinforcing each other, tightening the screws, ’Real black faces were not wanted for a very long time, and even today black actors get very few parts – there are few black faces to be seen on television and film apart from a handful of stars. It is possible to watch one Woody Allen film after another and not see a single black face.’

The tone throughout is chatty, almost akin to those urgent conversations, those attempted conversions, about music from your first forays into pubs and gigs – pushing the titanic figures onto your friends, establishing your canon. It is incredibly readable – pages, and years, simply fly by – built of short, clear sentences and rhetorical questions that pull you into the psychology or geography of Smith’s story. The rhythm of those rhetorical questions, their repetition, beats out across the prose like a blues refrain. And there is always that easy, unforced correlating of Kay’s own experiences and her slowly growing knowledge of Bessie Smith’s life. The chapter ‘Ruby on the road’ begins with Kay describing her best friend’s bedroom, two young girls singing at each other, obsessed with Bessie Smith, records, and slowly, it emerges, one another. Kay recalls reading about Bessie Smith having sex with women on the road and feeling she ‘could barely contain’ herself at the thought. There is something here of all teenage experience and yet simultaneously something very specific, something female, something to do with performance and emergent and complicated sexuality. The blended sensation for the reader is effortless, winning.

That blending plays out in other ways as well. The dynamism of Kay’s personal, autobiographical reflections and the various cultural, sexual and political implications of Bessie Smith’s life in her own time, and within the narrative of American history are never oppositional, never fenced off. Kay writes ‘Bessie Smith’s life lent itself to legends. Her life so aptly corresponded with her times that each seems emblematic of the other’ and yet she manages to create a throughly modern protagonist at the same time. The sexuality for example – complex and open, refusing the categorical, reads as an element of a life very much ‘emblematic’ of contemporary concerns. Or there is the discussion of the ubiquity of the surname ‘Smith’ across a range of early blues singers, with its linguistic reference to slavery, to the colonial past and its on-going reverberations.

The book’s ability to build an impression of Smith as something deeper, something more truly alive, than easily reached-for caricatures of sexual adventurer or hedonistic libertine, is testament to Kay’s formal approach. There is throughout an ease of voice and a loose, associative way of moving across the timeline of Smith’s life that creates a kind of cubist multi-dimensionalism. We see Smith through various lenses, often across a single page. Her relationships, then, are always cast in a multi-faceted light. Alcohol, the high life, food, money, her heterosexual marriages, particularly to Jack Gee, her homosexual promiscuity, the strange, intense relationship to Ruby Walker, even her sometimes friendly, sometimes antagonistic attitude to other blues singers – everything is rendered living, somehow, through Kay’s dynamic approach to her material.

The sense of un-naming, or perhaps the mutable nature of names is circled back on in Kay’s final chapter, where she describes Smith’s funeral and the lack of a headstone. The grave was unmarked until as late as 1970, with her family and ex-husband variously squabbling and conniving to evade responsibility for paying for a stone. ‘The graves of poor people, black and white, were not marked in the land of the brave, the home of the free. The graves of slaves were unmarked. It is like dying without a name. Like being nobody.’ It’s a powerful image which Kay extends into an unsettling idea and, as throughout the book, delicately sets her thought against the backdrop of the monolith of American pop culture and history. This section provides more of Kay’s unique, rather discomfiting, shifting of time – we learn about the headstone and the funeral before the focus doubles back onto the facts of Bessie Smith’s death, of rumours that she wasn’t seen to quickly enough at hospital because she was black, or was turned away a number of times, all of which caused her to bleed to death, of how that story stuck, became a kind of folktale of its own. Debunked by Smith’s original biographer, Chris Albertson, the story nonetheless holds particular poignancy for Kay, and the slippery essence of her own book, with its defiance of biographical convention, allows her to use the dialectic, rather than oppositional, nature of ‘truth’ and ‘lies’ to her own advantage. Kay’s instinct as a storyteller, as an interpreter and a knower of stories allow her to simultaneously elucidate and complicate that final symbolic act of Smith’s life, true or not.

It is perhaps complication that is the true triumph of Kay’s book. An evocation of a life, not a taxonomy of one – and, finally, an evocation of how a lifelong relationship with art complicates itself over time. Within the space of a couple of sentences towards the end of the book, for instance, we are told that Smith’s blues give Kay a ‘strange comfort’ and yet sometimes she ‘can’t bear to listen to Bessie Smith.’ Kay has managed to summon all the rich variety of Bessie Smith’s art and life and just enough of her own story into a book that never hectors, never romanticises, and yet never underplays its own intelligence and warmth for its subject. It’s something beyond biography, more like song perhaps. As Kay says in her own last passage, imaging Bessie’s final moments, ‘They don’t have any language in hell. No fucking words at all. It’s all sensations.’

Will Burns

You can buy ‘Bessie Smith’ by Jackie Kay here from the LRB Bookshop