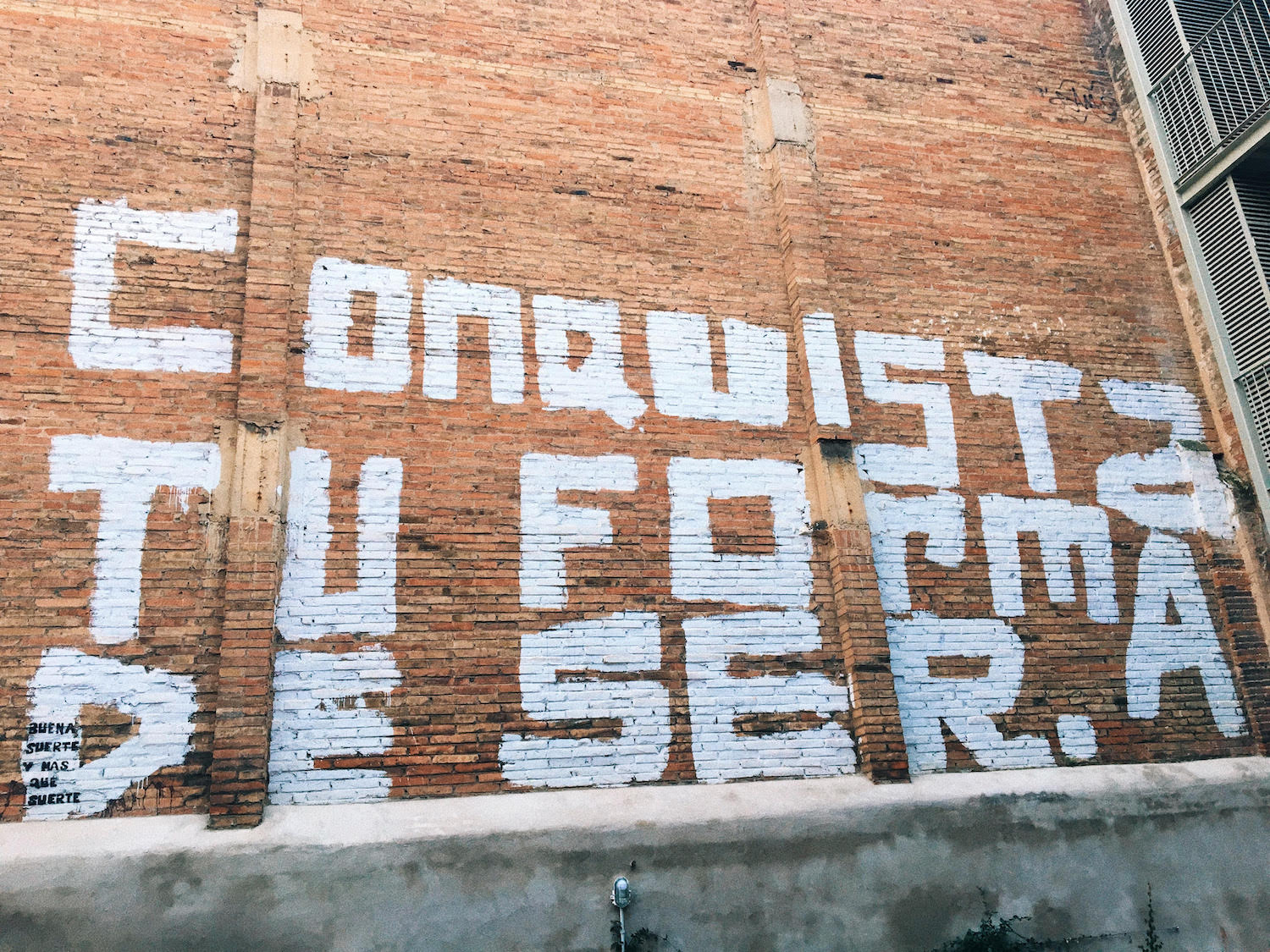

The view from the back yard. ‘Conquer your way of being.’

Speaking desperanto on the road to Lyon.

Early morning, before sunrise. Bleary-eyed in the back of a cab. Hurtling down Ronda Litoral. Head still spinning. Stumbling and mumbling through a conversation in broken Spanish—mine broken, the taxi driver’s rapid-fire and of the mother tongue (actually, that might be Catalan, but we’ll get to that later). I’m on my way to El Prat airport, flying to Lyon for the 2016 European Football Championship.

It’s not the breakneck drive or the lingua franca that’s making my head spin. And it’s not the word that the cabbie keeps repeating again and again, thumping his hand on the steering wheel, his dark eyebrows knitting in the rearview mirror.

‘Desastre, desastre, desastre.’

Now, my Spanish is far from fluent, but even I know what desastre means.

And the taxi driver isn’t talking about England’s performances in Euro 2016 (though the same word would have applied). He’s talking about the story blaring out of the tinny radio, the story dominating the news across Europe that morning, Friday 24th June 2016.

The morning after the Brexit vote.

The cabbie changes lanes without signalling. Horns whine in our wake as we weave along the coastline.

‘Desastre,’ he says again,

I can only nod and grip tighter on the grab handle. My phone buzzes in my pocket. I check the group text lighting up with the shellshocked responses from the boys flying over from London and Dublin.

Last sixteen knockout.

We’d been planning this Lyon trip for two years. The dates and a randomly selected match (thankfully not involving England) had been inked in the diary since before the EU referendum vote was even announced. As that date had got nearer, the press and politicians had started calling the whole thing “Brexit”—an ugly little portmanteau melding together two familiar words and disguising myriad mistruths. This Euro 2016 plan made with school friends—like my Brazilian wife’s plan to apply for an EU passport—was in the works long before Brexit came bulldozing through all of our lives.

No, that’s not true. It was always coming, we just weren’t paying attention. In fact, we were all sleepwalking towards it. Brexit was always looming on the horizon. Inevitable. Death and billionaires not paying taxes.

Fate had handed us tickets to the glamour tie of Switzerland versus Poland in the last sixteen knockout stages. But a spirited Ireland side would be playing the hosts France in Lyon over the same days we’d be there, so the city would be in a state of fever pitch. On the flight, I find myself wondering how the fans from our two nearest European neighbours will greet us when we arrive. The French and the Irish both have complicated relationships with the British at the best of times. And these were not those.

Nodding in fitful sleep. Murky half-dreams. Awoken by turbulence. Applause after landing.

On the shuttle train into Lyon, I find myself standing next to two Ireland fans, who’d been on the same flight over from Barcelona. Inevitably, we start talking about the referendum result.

‘Ah, don’t worry about it,’ one of them says. ‘We’re always doing referendums in Ireland. If you don’t like the outcome, just do another one.’

‘Yeah, we fucking love a referendum, man.’

‘The results aren’t legally binding,’ the first man says. ‘Cameron doesn’t even have to go through with it.’

At that moment, our roaming data kicks in and we all receive the same notification that the aforementioned British Prime Minister has just resigned (singing a little melody of indifference, I later discover). So it seems that he is going to go through with it. Or anyway, someone is.

One of the Irishman breaks the stunned silence. ‘Well, I guess now he’s got more time to watch West Ham. Or was it Aston Villa? I always get them two mixed up.’

‘Nah,’ says the other, ‘he wants to be down on the farm with his pigs.’

Our laughter catches a few sideways stares from the other passengers.

I start to feel a tinge of hysteria glowing at the edge of my jittery sleeplessness as we speed through the green blur of the French countryside towards Lyon.

Anyway, I could go on at great length about the warmth and compassion and sympathy with which my group was greeted in Lyon, both by the French and the Irish (people kept saying things like, ‘We love the UK, we don’t want you to leave.’ A sentiment we mirrored in return). I could tell you about watching France vs. Ireland while sipping Kronenbourg in a town square heaving with good-natured fans of both teams; about the tricolour flares going off in the crowd; about beers being thrown in the air whenever someone scored; about partying with the locals for three nights in the terrace bars with Fela Kuti blaring out of the speakers; about the hungover trudge up the winding hills to the Basilique Notre Dame de Fourviere, or cheering along with the Iceland fans as England limped out of the tournament. I could even bore you about the live match we saw between Switzerland and Poland, lit up by a single moment of brilliance from Victorian circus strongman, Xherdan Shaqiri, who levelled the game for the Swiss with an audacious bicycle kick right in front of our stand…

However, I originally set out to write about my adopted home city of Barcelona, and life here since those days in June 2016.

‘The new people.’

I’m an immigrant here in Barcelona. Not an expat. That word, to me, is a word of colonialism, of English exceptionalism, a word I now associate with Brexitland. I’m an immigrant here—although, I’m well aware, one who is made to feel welcome. My experience is without doubt profoundly different from that of the North African and South Asian people who have also made the city their home.

My wife Marina and I live in the neighbourhood of Poblenou. In Catalan this translates as ‘the new village’—but the literal meaning is ‘the new people.’ This feels somehow appropriate given the influx of new residents from overseas into a once locals-only area. We are the gentrification in Poblenou. Outsiders (involuntarily) driving the rent up and the locals out, while artisan coffee shops and eateries pop up like bluebells in spring. We didn’t mean to be part of this shift. The landlords just saw us coming. The same thing happened in Nunhead and Peckham, the areas in southeast London where I grew up.

Poblenou was once an industrial expanse serving the city’s port. In the build-up to the 1992 Barcelona Olympics, the port was redeveloped into an artificial beach to attract tourists and locals. A friend once told me that the sand was imported from the Sahara Desert—so even the sand is from somewhere else (okay, I’ve laboured my point). In spite of its proximity to the beach, Poblenou is less touristy than the central neighbourhoods of Raval, El Born or Gràcia. The former warehouses and factories have been transformed into design studios, art galleries, music venues, and apartment complexes. Every month, two or three street blocks are torn down and more cranes appear on the already cluttered skyline.

Our apartment building used to be a squat, and even several years after the fact, we get the occasional nomadic wanderer knocking on the street-level door looking for a place to crash. The only other trace left of those days is a massive white scrawl of graffiti in our shared garden that reads: ‘Conquista tu forma de ser’ (‘Conquer your way of being.’). Inside these white letters, in smaller black ones, is written: ‘Buena suerte y más que suerte’ (‘Good luck and more than luck’).

“It’s fucking Disneyland, man.”

We live within walking distance of half-a-dozen music venues (including famous superclub Razzmatazz), all of which have been shuttered since the first COVID-19 lockdown last March. The people who run these venues recently started the campaign ‘The Last Concert’ (‘El Último Concierto’) to get funding or face imminent closure. The loss of these mainstays would tear the heart out of Barcelona’s late-night music and clubbing scene. Because Barcelona, maybe more than any other city in Spain, truly comes alive at night.

‘Ah, but Barcelona isn’t Spain,’ a Madrileño barman in London once told me. ‘It’s fucking Disneyland, man.’

He meant this as an insult, of course, one evoking an international playground full of tourists and immigrants, where even the locals aren’t truly Spanish, but instead Catalan. Some Castellano Spanish like to give the impression that people from the more affluent and culturally-independent Catalunya are aloof and closed-off, even choosing to speak their own language to further set themselves apart. While this is very far from the truth, in my experience, Catalans do take longer to get to know than people from other parts of the country. But once they trust that you’re not a complete idiot, they are warm, loyal, and fun-loving. And anyway, it’s not surprising that Catalans are protective of their language and culture given the fraught recent history of the region.

I’m not going to delve into the horrors or complexities of the Spanish Civil War or the roots of the separatist movement in its aftermath. I’m no expert on the subject. And many will already be familiar with the accounts of George Orwell, Ernest Hemingway, and Martha Gellhorn—while the work of exiled Catalan and Spanish writers Mercè Rodoreda and Arturo Barea are also recommended reading on the subject.

Marina and I have friends on both sides of the separatist argument. Back in 2017, before the violently crushed Catalan Independence Referendum, I heard certain pro-separatist voices evoking Brexit as an example to follow for their own cause (albeit from a leftwing perspective rather than one of rightwing disaster capitalism). Those people have stopped making this comparison in the years since.

One thing’s for certain, after 2017 it has become increasingly difficult for anyone to argue against the notion that Catalans have been ill-treated in their own country. And the horrific scenes of military police beating and brutalising peaceable citizens—including the elderly and families—during the chaos of that October election, have only helped convert more people to the separatist cause. The Prime Minister at the time, Mariano Rajoy, did what all weak men do when dialogue has failed—he lashed out with violence. Rajoy is gone now, but the scars of those brutal days, and the ghosts of the atrocities of the past, remain unhealed.

The yellow ribbons worn and displayed in support of the Catalan politicians imprisoned in the wake of the failed referendum can still be seen on apartment balconies across the city. Someone in Poblenou has spray-painted this yellow ribbon on the pavements approaching the beach, bringing to mind a slogan from the May 1968 protest movement in France, ‘Under paving stones, the beach!’ (‘Sous les pavés, la plage!’).

Someone else living in our neighbourhood has spray-painted red swastikas over these ribbons.

On Sunday 14th February, the people of Catalunya voted in regional elections dominated by the independence debate and the handling of the pandemic. The election saw the pro-independence parties increase their parliamentary majority—though it was the unionist Catalan Socialist party (PSC) that took the largest overall share of the vote. The far-right Vox party also won its first seats in the region. But the pandemic led to a low voter turnout, so it’s hard to know whether the results fully reflect the spectrum of public opinion here.

The virus has hit Catalunya and the wider country hard. The lockdowns have ranged from strict (March-June 2020) to lenient (October 2020-the present). But the hardliners on both extremes of the coalition government use every new lockdown vote as a stick with which to beat incumbent PM Pedro Sánchez of the Spanish Socialist Workers Party. And as in Britain, Hungary, Brazil and beyond, the far-right in Spain is on the rise. And the ghosts of the Civil War stir from their fitful slumber once again.

The last week has seen more protests and skirmishes on the streets of Barcelona. The recent arrest of Catalan rapper, Pablo Hasél—who faces nine months in prison for allegedly glorifying terrorism and slandering the Spanish monarchy in his lyrics—has led to large demonstrations against this perceived threat to freedom of speech, and ignited running battles between protestors and the police in the city centre. The acrid black smoke from dozens of torched plastic rubbish bins hangs over the skyline, bringing back memories of those turbulent days of 2017.

Days of books and roses.

When I first went to Berlin, in my early twenties, I thought that it was the greatest city in the world. The bars and clubs, parks and parties made Berlin seem impossibly exciting. Visiting Barcelona for the first time five years later, I saw that it had that same energy. But with beaches and mountains and great weather and better food. One other thing that these two powerhouse European cities share is a seriousness about culture.

In this era of so-called Culture Wars—where our own government and the toxic UK press sneer at and neglect art and literature and music—it’s refreshing to live in a city where culture is something that everyone can enjoy, no matter their social background. Even during the pandemic, exhibitions, markets, outdoor concerts, and literary talks have continued to flourish.

One annual event that demonstrates this dedication to culture is the way Catalans celebrate the day of their patron saint, Sant Jordi. The English will know this figure as Saint George. The 23rd of April in “Blighty” brings out a swaggering defiance from a small band of deluded idiots high on the fumes of sovereignty, riled up by the parasitic press barons and poisonous snakes like Farage and Yaxley-Lennon. You know, flag-flying and bad tattoos, bollocks being talked about better bygone days, drinking imported lager under white and red bunting, blaming immigrants for all the ills of the world.

In contrast, La Diada de Sant Jordi is the Catalan equivalent of St. Valentine’s Day—only a less cynical version than our own. The ramblas are suddenly full of book stalls and people selling flowers—the traditional gifts that Catalans give to their significant others. The mood in the streets is romantic, good-natured, family-friendly, and cultured.

Since 2018, however, the 23rd of April has also become a political focal point. Some florists have replaced the traditional red roses with yellow ones (to match the ribbons) in solidarity with the jailed Catalan politicians. While this politically-charged atmosphere might draw parallels with the English “celebrations” of the same day, there’s a world of difference. The Catalan’s protests are focused on a specific injustice rather than some nebulous, tabloid-fuelled fury.

Saint George was himself an immigrant, of course. A Turkish-born Greek with a Palestinian mother who served in the Roman army and later travelled across the Mediterranean looking for refuge. In June 2016, George of Lydda would have been the sort of person that Nigel Farage would’ve slapped onto a poster under the tinderbox words BREAKING POINT.

“All these things will I give thee…”

Life is quieter here now as we wait out the virus and our turn at the front of the vaccine queue. The shared roof terrace of our apartment building has been a real saviour, especially during the first lockdown. I go up there twice a day to stretch my legs and get the grey matter going again. From the terrace, I can see the spires of Antoni Gaudí’s ecstatic fever dream monument to Christianity, the Basílica de la Sagrada Família, growing ever more gnarled and strange almost 140 years after they first broke ground on it. I can also see the mountain of Tibidabo where, they say, el Diablo himself tempted Jesus Christ by gesturing to the vistas that they gazed upon and saying, “All these things will I give thee, if thou wilt fall down and worship me.”

Another poisonous snake dripping venom and empty promises.

who lived next to my Poblenou studio and who died during the pandemic.

From punch-ups to punchlines.

The tourists are gone now. The stags and the hens and the bar crawlers and the beach lobsters and the weekend punch-ups in the city centre are all just a hazy memory. The happy hour deals have been rejigged to serve the local people, who have slowly been rediscovering parts of their city that for decades were the tourist-packed areas they avoided.

People in Barcelona aren’t talking much about Brexit anymore. Understandably, the pandemic is using up most of the collective mental bandwidth. When people do mention Brexit to me, it’s usually with bafflement that the whole thing is still dragging on (or that it happened in the first place). Sometimes they make jokes. Here’s one a French friend told me during the period of endless delays.

What is “making a British Exit” from a party?

When someone keeps saying they’re leaving—but never does.

Only now we have left, and somehow the joke doesn’t seem funny anymore.

There is, however, one Brexit joke that I still think back on fondly.

Me and my school friends were traipsing through some suburb of Lyon heading towards the football stadium. I’d gone into a pharmacy with my mate, Alex, trying to buy sunglasses, the day having suddenly turned bright (quelle surprise!). We were met with a range of shrugs and head shakes from the staff behind the pharmacy counter. As we exited empty-handed through the automatic doors, we heard the sombre-faced middle-aged chemist mutter a single word.

‘Brexit.’

We laughed (and squinted) all the way to the stadium.

I like to imagine this quiet chemist at home on some future Sunday, cooking and listening to the Tour De France on the radio, chuckling to himself as he remembers the glorious time he delivered that most uncharacteristic of zingers, dispatching les rosbifs with a casual nonchalance he had forgotten he’d ever possessed.

In Barcelona in 2021, the only person who still regularly talks to me about Brexit is my landlord, Jaume (another Catalan cabbie). Nearly five years on, he shakes his head in disbelief at this act of national self-harm.

‘Brexit,’ he says, es un desastre’.

‘Absolutamente,’ I say.

Because it’s as true now as it was back in June 2016.

James Connor Vincent