We’re honoured to publish an extract from Rob Young’s The Magic Box. Dreamt up as a companion piece to Rob’s peerless 2010 book Electric Eden, The Magic Box does for British television what Electric Eden did for this country’s post-war folk music. In this extract, Rob blows the dust off a dystopian classic broadcast by the BBC in 1968.

Nigel Kneale’s project of 1968 advanced from depicting Orwell’s Big Brother (in a BBC adaptation he wrote in 1954, starring Peter Cushing) to predicting the reality television of Big Brother. The controlling function of the two-way ‘telescreen’ in Orwell’s novel – described as ‘an oblong metal plaque like a dulled mirror which formed part of the surface of the . . . wall’ – appears to have lingered in Kneale’s imagination. Broadcast on BBC Two’s ‘Theatre 625’ strand in 1968, and repeated only once, as a ‘Wednesday Play’ in 1970, The Year of the Sex Olympics (Michael Elliott) is one of the great lost classics of British dystopian television. Its speculations about where permissiveness and the sexualisation of mass entertainment might end up appeared just as the 1960s counter-culture was peaking. In the ‘sooner than you think’ future depicted in The Year of the Sex Olympics, mass entertainment has merged competitive sports on circular beds in a debauched travesty of Strictly Come Dancing with sexual prowess. Grinning couples compete against each other or The Great British Bake Off. In a crude foreshadowing of X-Factor-style public voting, or the bellwether of social media ‘likes’, real-time audience feedback is monitored in the ‘production pod’, under the guidance of a team led by Ugo Priest – a brilliantly cynical performance by Leonard Rossiter – a member of the educated elite conscious of the populist processes at work even as he espouses the TV station’s ‘cool the audience, cool the world’ philosophy.

By now, Kneale’s long experience of working within the television industry had clearly made him dubious about the power of the medium and aware of its steadily degrading quality. Written in a climate of increased explicitness in controversial stage musicals like Hair and Oh! Calcutta, and coinciding with the globally televised 1968 Olympic Games in Mexico, Sex Olympics reflected an insider’s distrust of the mass entertainment industry, as well as being an early example of the culture of television exhibiting a growing self-awareness.

In addition to the Orwellian echoes, Kneale synthesised Aldous Huxley’s soma-tranquillised future with the more contemporary speculations of J. G. Ballard in depicting an enervated society whose desires and rebellious instincts are held in check (‘apathy control’) by a surfeit of sensationalist entertainment. The character played by Brian Cox (who half a century later would take a major role in HBO’s Succession, a series that also deals with the deadened souls running a multimedia conglomerate) is named Lasar Opie. This rising studio hotshot gets off on zapping opium to the people via the cathode-ray tube.

As in Orwell’s vision of Airstrip One, societal fault lines in Sex Olympics are appearing between proles and the educated elite, labelled as ‘low-drives’ and ‘high-drives’. In this world–sanitised, dumbed-down and insulated from the outdoors (as in The Machine Stops) – the greatest distaste is reserved for the concept of ‘tension’, a word that has replaced memories of war. Anticipating the early twenty-first century’s obsession with ‘safe spaces’ and the banning of ‘triggers’ in public life, here anything suggestive of upset or trauma – and even horrific images such as expressionist paintings of contorted human screams – ignite wailing and a gnashing of teeth in the closely monitored audiences.

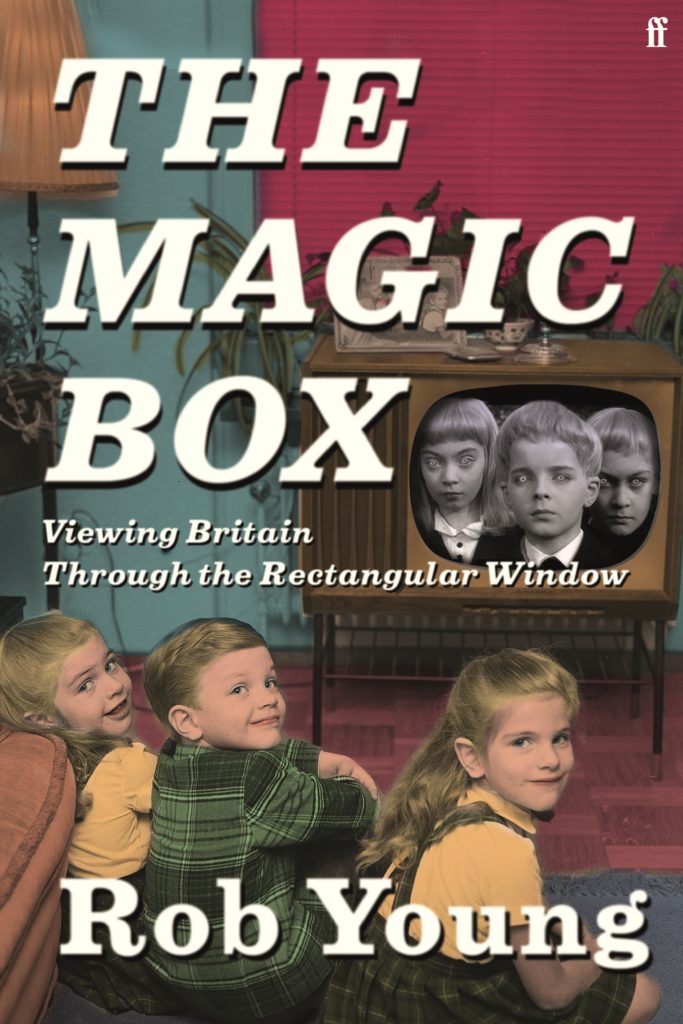

The only surviving tapes are in black and white, but Sex Olympics was originally one of the BBC’s first forays into colour. The actors playing the high-drives had their skin painted gold and their costumes were Carnaby Street on steroids – psychedelic swirls of purple, red and green. The extrovert Misch, with her mirrored hair extensions, is the epitome of this gaudy decadence, but Turner’s performance harbours hidden reserves of melancholy. None of Kneale’s characters fall into easy stereotypes or caricature. Liberated from the aggression of former generations, they come across as adult children playing power games with their fellow humans’ impulse control. Kneale’s fear of a trivialised and infantilised culture had already found expression in an unfilmed script, ‘The Big, Big Giggle’, from 1965, about youthful suicide cults. In The Year of the Sex Olympics, he planted seeds of dissatisfaction among the proponents of the cult of television. Square-jawed Nat Mender, whom Kneale summed up as a ‘decahedral peg in a nonahedral hole’, is beginning to believe the medium should be used to educate, rather than sedate, the masses.

The entire first half of the film is confined to the extraordinary interior sets representing ‘Output 27’, the TV studio and the junior facility where parents store any inadvertently produced children. We have no idea whether this brittle architecture of steel, glass and plastic exists in a tower block, a giant media centre or even an underground bunker, but it is the only environment they appear to know. Kneale’s script notes described it in these terms: ‘The whole of Output has a vague feeling of being indoors but nowhere in particular. One place blurs into another to form a worldwide long-house for this retribalised McLuhanised society.’ As they monitor their TV output or hang about in the recreation areas with their nipple-substitute protein lollies and robotic chess machine, the characters, shot in spangly facial close-ups, reveal the moral parameters of this future world and hint that it emerged in the aftermath of a devastating global conflict. Kneale’s linguistic inventiveness is given free rein with their mode of speech – a mid-Atlantic hipster patois, condensed by missing pronouns and evocative synonyms that unconsciously reveal a richness of life that has been lost.

Just after the halfway mark, an unforeseen tragedy signals a gear shift in the action. Just as viewers’ sensibilities are becoming blunted by ever more explicit porn and moronic cream-pie fights, the brooding Kin Hodder, a troubled high-drive with a visionary new concept of art (‘pictures’ that last for ever), falls to his death while attempting to hijack a live broadcast and flash some of his disturbing paintings on national television. The monitored audience think it’s hilarious, breaking the cycle of boredom and inertia and boosting the ratings. The controller and his team come up with a plan for a new series, placing a couple on a remote uninhabited island and observing their attempts to survive in the wilderness. As many commentators have noted, The Live-Life Show’s fly-on-the-wall format predicted the reality television hits of thirty years later, such as Big Brother, Castaway and I’m a Celebrity . . . Get Me Out of Here! Its outdoor scenes were filmed on the rugged, sea-lashed clifftops of Kneale’s birthplace, the Isle of Man.

Nat and his colleague/former partner Deanie Webb have taken the unusual step of having a child together and feel unarticulated yearnings for a better quality of life (‘We’d be something called a family’). They volunteer as the first subjects, despite obviously never having spent a second in the open air. Dispatched to the island bundled up in thick coats, and barely knowing how to strike a match or prepare food, they live out the Digger dreams of the hippie counter-culture, pitching up in a draughty crofter’s cottage, just as Paul McCartney, at his Scottish farmhouse, or folk musicians like the Incredible String Band and Vashti Bunyan were doing around the same time. Anyone who has ever searched out practical instruction videos on YouTube will recognise Nat’s desperate resort to his tape-recorded guide on how to make fire or bury a body.

In this windswept Garden of Eden, Nat, Deanie and their daughter Keten experience a sense of vitality and self-sufficiency they have never felt before. The strangeness of the cottage and the wilderness forces them to confront their previous state of blindness. ‘We found our place,’ says Deanie, and they have found happiness in spite of the cameras’ perpetually vigilant eye – out on the moors, chasing sheep, laughing at dangers, gadding about in a prehistoric stone circle down by the cliff edge. The process of an urban, technological elite rediscovering the landscape, handmade furniture and running water is superbly acted by Suzanne Neve and Tony Vogel, like aliens discovering an unfamiliar planet. The wonder finds visible expression in Vogel’s wide-aperture eyes, at times recalling a face out of the silent era. These are eyes large enough to gobble up the contents of his monitors back home, but also wide enough to take in the immense landscapes of the Isle of Man.

This later turn in the story brilliantly inverts the prevalent ‘get ourselves back to the garden’ mentality. This society may have lost some of its ‘old-days’ hang-ups and inhibitions, but out with the bath water has gone much of what made us human – love, parental attachment, privacy, permanence. In The Live-Life Show, television unconsciously begins to point the way back to some of what this future has rejected or forgotten.

Dumped in the wild in their fur-lined anoraks, they are reduced to the state of Stone Age primitives – then they meet a real fur-clad wild man. Grels tells appealing stories, understands the cyclical and tidal rhythms of nature, and most importantly, knows how to hunt and forage for food. When Keten develops a fever and dies, it feels like Nat and Deanie have crossed a threshold, no longer insulated from death or its emotional fallout.

The nasty, brutish and short ending, with its clear influence on signature sequences in both Michael Reeves’s Witchfinder General (1968) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (1980), is a landmark in the British televisual grotesque. The complexity and density of ideas Kneale deploys throughout the film extend to the final seconds. While the production-pod crew celebrate the hysterical audience reactions, it dawns on Ugo Priest that Nat, in his murderously vengeful state, has attained a level of existence that’s been denied to his fellows. The credits roll with that mental state of horrified consternation hanging in the balance.

Given the problematic nature of the production, with its hi-tech sets, screens within screens and all-terrain outdoor unit, as well as the industrial action by studio electricians that held up filming, it’s a miracle The Year of the Sex Olympics ended up getting made at all. In addition, the script and its provocative title were catnip to the National Viewers’ and Listeners’ Association, with its founder, the clean-up TV campaigner Mary Whitehouse, trying to halt filming. If she had taken the trouble to read it, she might have realised that Kneale’s position – as a critic of the effects of pornography and permissiveness, rather than a champion – was not so far from her own as she thought.

The Magic Box by Rob Young is out now, published by Faber. Available to purchase from Rough Trade.