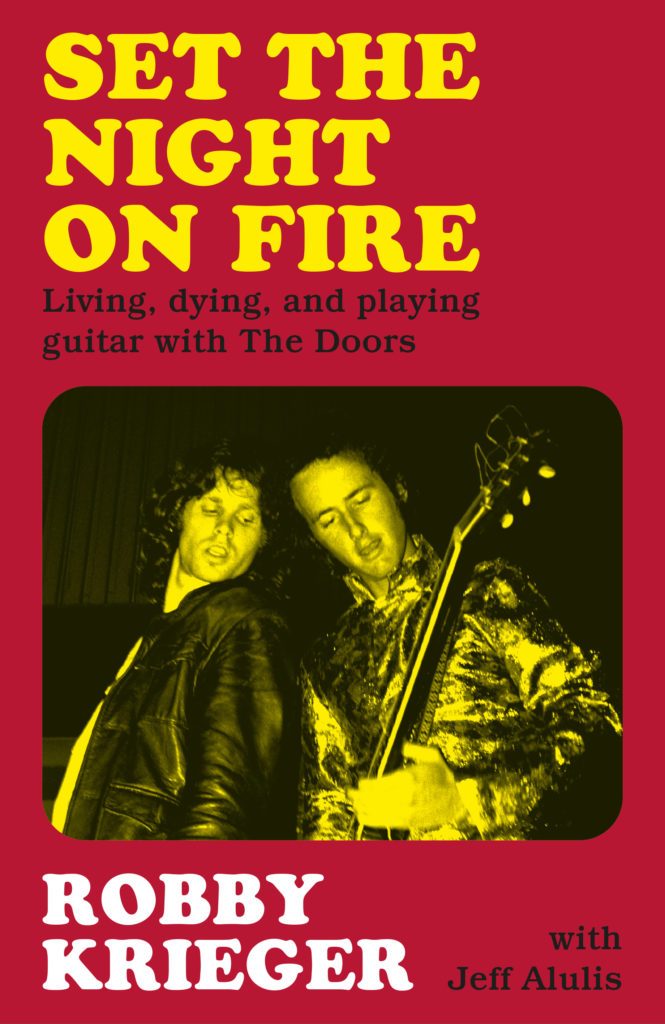

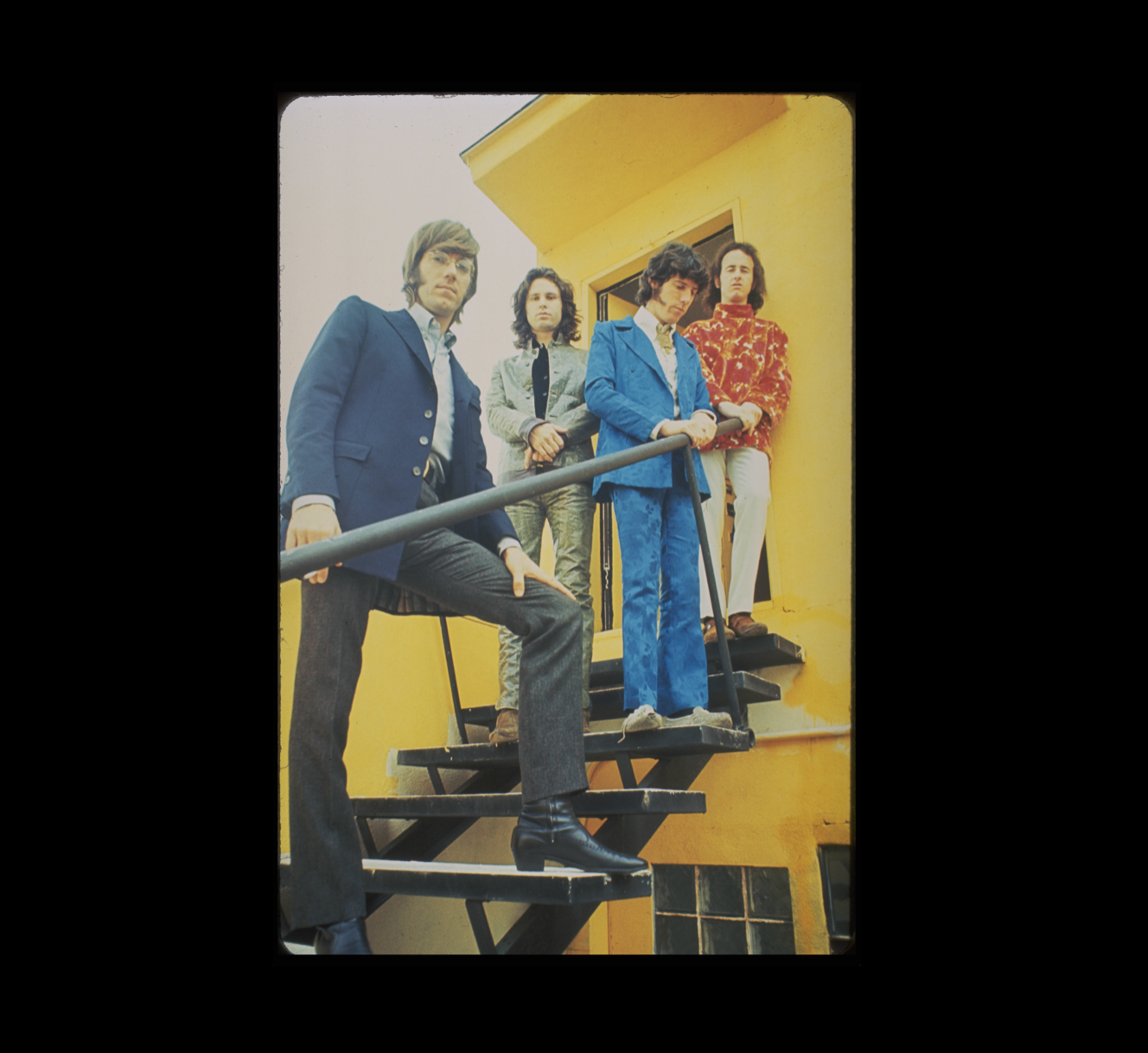

My love for The Doors is such that I have been known to walk out of bars, exit cabs and terminate friendship when others disagree with the quality of their radical legacy. The Doors’ impact on the evolution of rock n roll was the equal of any of their peers before or since and their story has the narrative drama, power, glamour and tragedy of archetypal myth. Robby Krieger’s memoir tells the story of the band and his creative life and struggles following it with the knowledge and intimacy of a true insider. Set the Night on Fire is an essential addition to the canon of great rock n roll memoirs by a survivor who was witness and participant in a cultural revolution. We are excited to share the first extract from Robby’s memoir here with a link to pre-order limited signed copies.

Lee Brackstone

A devout Buddhist once approached me, positive that he had deciphered the secret meaning behind “Light My Fire”:

“It’s the fire that burns in your third eye.”

I said, “You’re right, man.”

Jim always told me not to tell people the intended meaning behind my lyrics. “Let them interpret it. Sometimes they’ll come up with a better idea than you had.” The third eye concept wasn’t what I intended, but it’s my favorite interpretation so far.

When the Doors first started, we only had a few songs from the original demo and a few others we were working on. Our live set was mostly rounded out with covers: “Gloria” by Them, “Don’t Fight It” by Wilson Pickett, and our own version of John Hammond Jr.’s version of Willie Dixon’s “Back Door Man.” Jim encouraged the rest of us to bring in some lyrics because we didn’t have enough original material, and he didn’t want the sole responsibility for songwriting on his shoulders. This is a crucial detail about Jim Morrison that often gets lost in discussions about our band. Many people think of Jim as an auteur who came in with fully formed ideas and fearlessly captained the creative process. I don’t want to take one shred of credit away from Jim’s massive contributions; I want to give him additional credit for being a true collaborator. He never let his ego claim the territory of Main Songwriter. He was never so precious with his words that we couldn’t offer lyrical input, and we enthusiastically welcomed his invaluable ideas for musical hooks and melodies. On the majority of our albums the songwriting is credited to “the Doors” rather than any of us as individuals. That was Jim’s idea, long before any of our singles made a splash. Even though he likely stood to make more money by crediting himself as the main lyricist, he thought it was important that we remain united and not squabble over the genetic makeup of every single song. Even on later albums where songwriting credits are listed individually, we still split the money evenly among all four of us. Jim always wanted what was best for the Doors as a whole. When Jim tasked us all with bringing in original material, though, I was the only one who gave it a shot. Jim always talked about using “universal” themes in his lyrics that would stand the test of time, and speak to people of the past, present, and future equally. It occurred to me that there was nothing more universal than the four elements: earth, air, water . . .

Fire.

There it was. The element that could warm you or burn you. The stuff of ancient Greek myths. A metaphor for love and lust, or a sly reference to lighting a joint. The Rolling Stones had previously cracked the Billboard top one hundred with a song I liked called “Play with Fire,” so I figured I was on the right track. I sat in my room strumming my Gibson SG Special with the Stones song on in the background and tossed around phrases until finally it clicked.

Light My Fire.

I was still gathering my lyrical confidence, so I only managed to put together a verse and a chorus. Musically, though, I wanted to show off a little. Standard rock songs generally used only three chords. I decided I would try to use every chord I knew. I started off with G, D, F, B flat, E flat, A flat, and A, but I worried about going overboard, especially with the flat chords that were so rarely used in rock ’n’ roll. I pared down the verse to something simpler: A sus 2 to F sharp minor, and back again. (Everyone who covers the song always plays some form of an A minor instead of that A sus 2 because Ray’s organ part fills in the notes I’m not playing and creates an aural illusion. A small but perfect example of why the Doors worked best as an ensemble.) I kept the chorus simple, too, using a classic G, A, D progression. But I couldn’t resist throwing in a B7 and an E7 to at least keep it interesting.

The next day I sang and played my new song for the band. Jim came up with the second verse about the funeral pyre. I poked fun at him for always wanting to write about death and funerals, but Ray loved it: “It’s cool! It covers the whole spectrum of getting higher and going lower!” Jim’s other stroke of genius was changing the last line of the chorus. Originally it was just the phrase “Come on baby, light my fire” three times in a row, but Jim suggested a simple but effective change: “Try to set the night on fire.” While I had originally written the tune with a folk sensibility, John gave the song much-needed dynamics, with a Latin-inspired rhythm that built a sultry mood during the verse and offered rock ’n’ roll release during the chorus. Later he would put a rim shot crack at the beginning, starting the song on the four rather than the one, which was another simple but essential contribution. As Ray and I struggled with a way to get from the solo back to the verse, I took the opportunity to throw in all the original chords I had been so worried about. Even those poor, overlooked flats. The whole composition ended up unintentionally walking a wobbly line between what’s technically called a circle of fifths and a circle of fourths. It was a rarity at the time to construct a pop song that way. The end result sounds deceptively simple, but when you include the A minor 7 and B minor 7 that form the bedrock of the solo section, it adds up to a total of thirteen unique chords. I’m glad I didn’t know more about music theory at the time; otherwise I might not have had the guts to break the rules.

Robby Krieger

Preorder a signed copy of Set The Night On Fire!