flaneur

noun

a man who saunters around observing society

—————————

Of all Andrew Weatherall’s many celebrated talents, the most under-appreciated might be his accomplishments in the itself under-appreciated pursuit of flaneuring.

Thursdays were Andrew’s day to flaneur, or as he sometimes put it, perambulate around the West End. And he saw this as a civilising activity. He would visit record shops, clothes shops with the scent of Japanese denim in his nostrils (Son of a Stag and the Vintage Showroom were particular favourite haunts), hat shops, and bookshops. Sometimes he would visit his hairdresser, ‘Itchy’ Chris. I have no doubt his retail (and grooming) interests were broader than this snapshot portrait, but I suspect these were his main destinations most Thursdays. And I know the respective barbers, tailors, booksellers and purveyors of fine vinyl feel the absence of his frequently irregular visits acutely.

He would often wander by the offices of Faber on Bloomsbury Square and sometimes we’d head out for cod, chips, peas (mushy), a slice and a cup of tea at the Fryer’s Delight on Theobalds Road. He’d tell me about his latest, often obscure, literary discoveries, pass me a CD of a recent deepdive mix into Youtube (most definitely not featuring the ‘umpty-bumpty’ music he played in clubs the world over) then be on his way into Shoreditch, Cambridge Circus, Mayfair (where I think he picked up his magnificent cologne) or Soho. He loved flaneuring and the tradition of the flaneur as represented by Baudelaire, Walter Benjamin and more recently writers like Iain Sinclair; writers who submit to the tides and currents of a city and the life force it creates. It was no surprise then, that Andrew found a kindred spirit in Michael Smith, a writer who captured the fin-de-siecle mood with this tradition in mind when he published his first book, Giro Playboy (2003).

Andrew was aware of this book and Michael before I introduced them and proposed the idea of a collaboration on Unreal City back in 2013; of course he was, and of course he would be. As Andrew was fond of saying, ‘If you’re not on the margins you’re taking up too much room’ and Michael had made the margins of the cultural life of the city his home since the late ‘90s when he moved down here from Hartlepool with romantic notions of what might constitute a ‘literary life’. First published in a limited edition pizza box run of 100 in the form of 8 separate pamphlets and a signed pebble, Giro Playboy is a memoir but very much of the unreliable kind. It survives as a curious document of the turn-of-the-millennium counter-culture in Hoxton and Shoreditch, of which Andrew Weatherall was very much a part. Pubs like The Bricklayers Arms and The Griffin, where Michael ‘researched’ much of the book from behind the bar, were still largely off the map at this point, twenty years ago. But gentrification was marching that-a-way, and I know Andrew admired Michael’s portrait of a community shifting gear. Giro Playboy anticipated the nostalgia for a grubbier, less self-conscious East End, before it went mainstream and out-Nathan Barley’d its own satirical shadow. As Andrew himself puts it, in his characteristically effortless and elegant way in the Introduction to the book:

There are two ways to deal with the loss of a personal bohemia. The first, easiest and most soporific is nostalgia: a vision of a probably non-existent Arcadia with all hardship and regret expunged. In some this is fuelled by an envy of the young. Nostalgia is one of humanity’s default settings, and has been for countless generations. I would imagine the original denizens of sixteenth-century Soho (though it was admittedly not known by that name until some years later) complained that the sport (in their case hunting) was not what it had been, just as the denizens of sixties Soho bemoaned the fact that the sport (in their case carousing) was not what it had been. And so on, and so forth. Paradoxically, although nostalgia can be mentally debilitating for its practitioners, it is also part of what attracts the next generation of demi-monde to a particular locale. A demi-monde that brings an area to life and, more often than not, eventually brings property developers to the area.

The second way is the path of wistful resignation with a homeopathic droplet of cynicism. This is Michael Smith’s way.

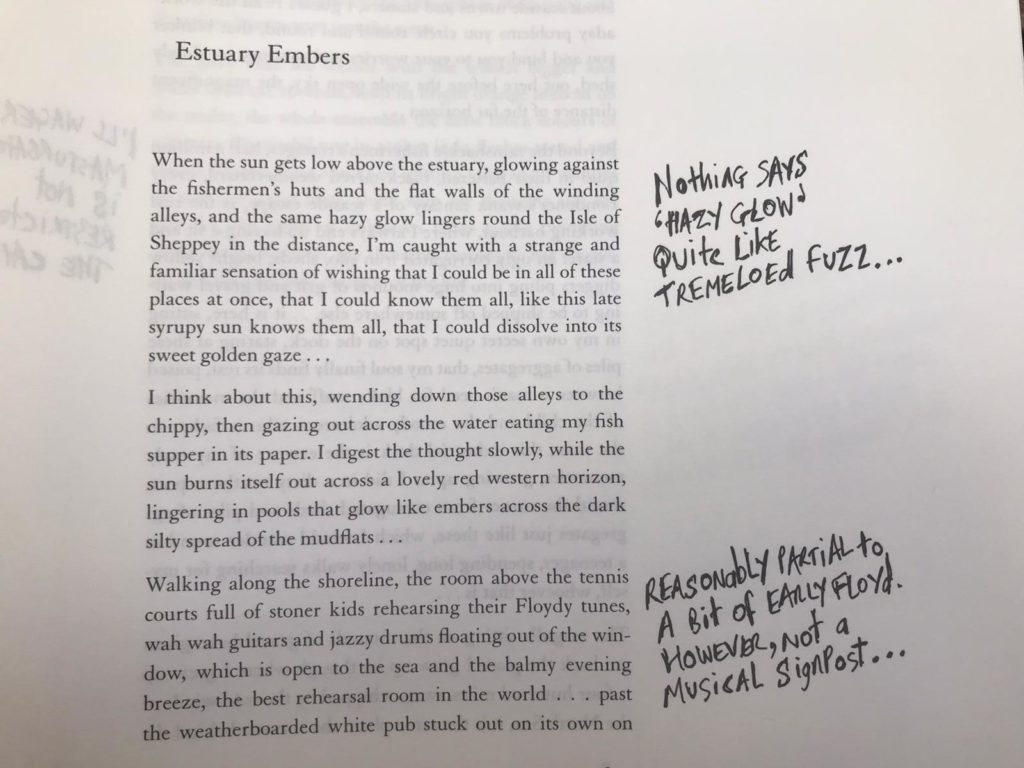

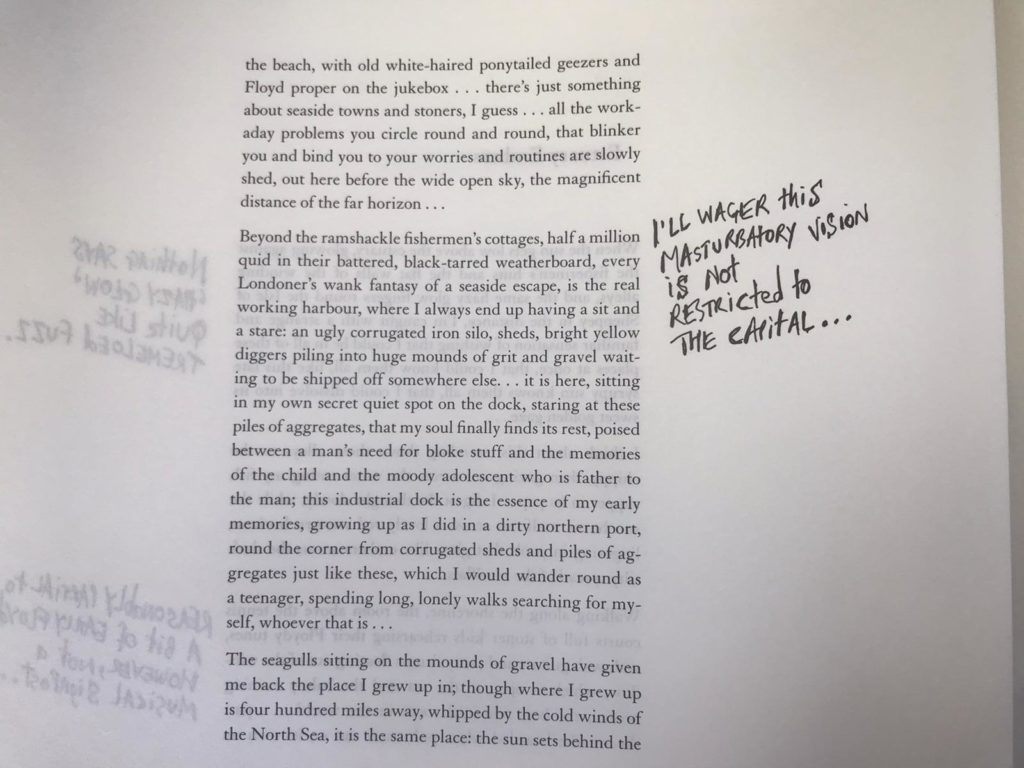

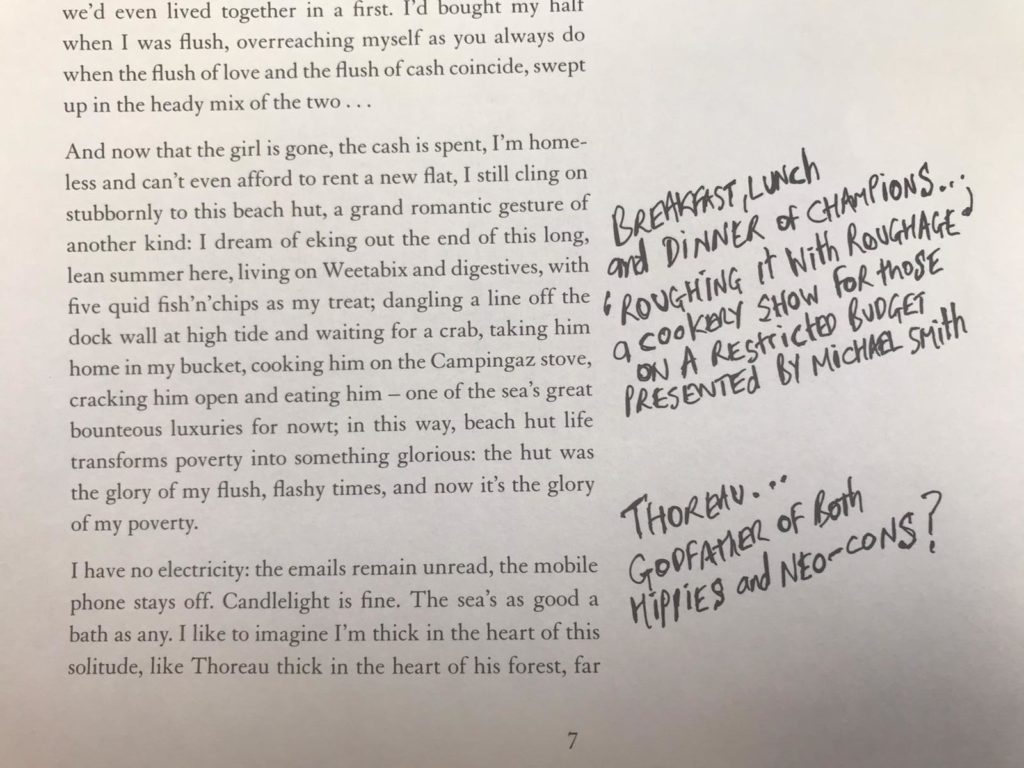

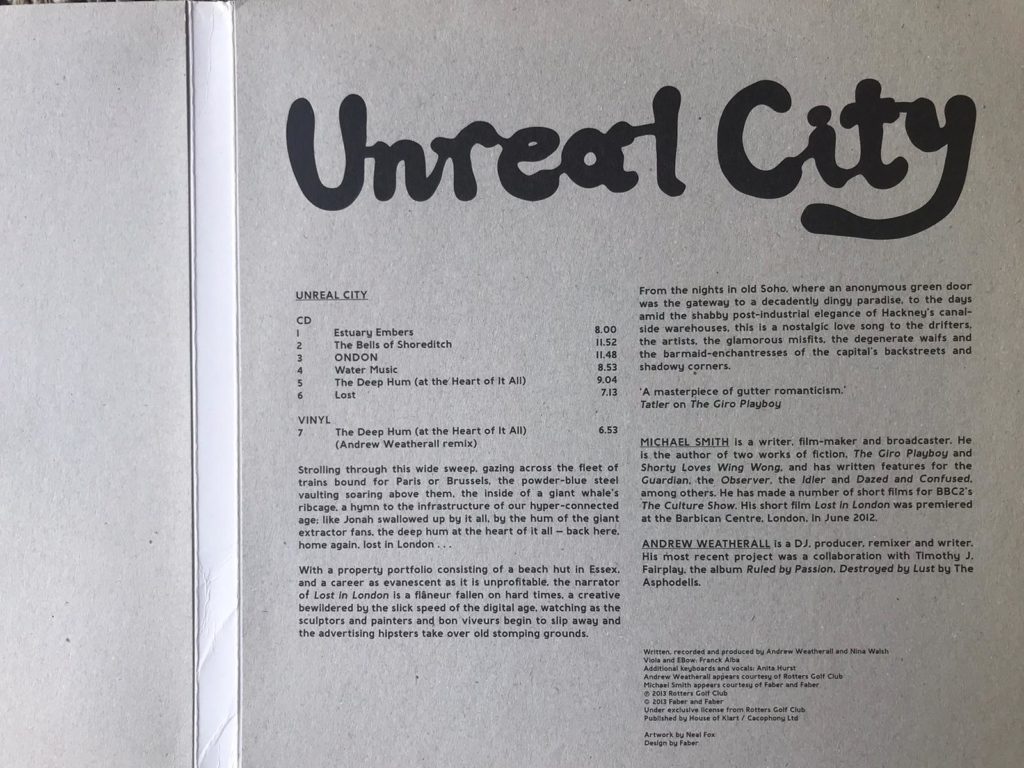

Andrew also loved Michael’s voice: a lugubrious, softened Tees-valley drawl that never loses its lustre, even when he’s writing about the most compromising and debased of circumstances. They collaborated on a 10-inch and CD only 1,000 copy limited edition of UNREAL CITY; a search of which online only yields this single track, The Deep Hum (at the Heart of It All). Andrew also annotated the pages of the book in this edition with notes in the margins, some of which are reproduced here. A cheeky homage to T.S. Eliot’s ‘unreal city’ immortalised in The Waste Land, Andrew’s collaboration with Michael (‘when Giro met the Chairman’) is mercurial and melancholic, wistful and whimsical. It is a record of the past as we see it recorded before our very eyes as the present disappears in a fugue of incense.

Lee Brackstone