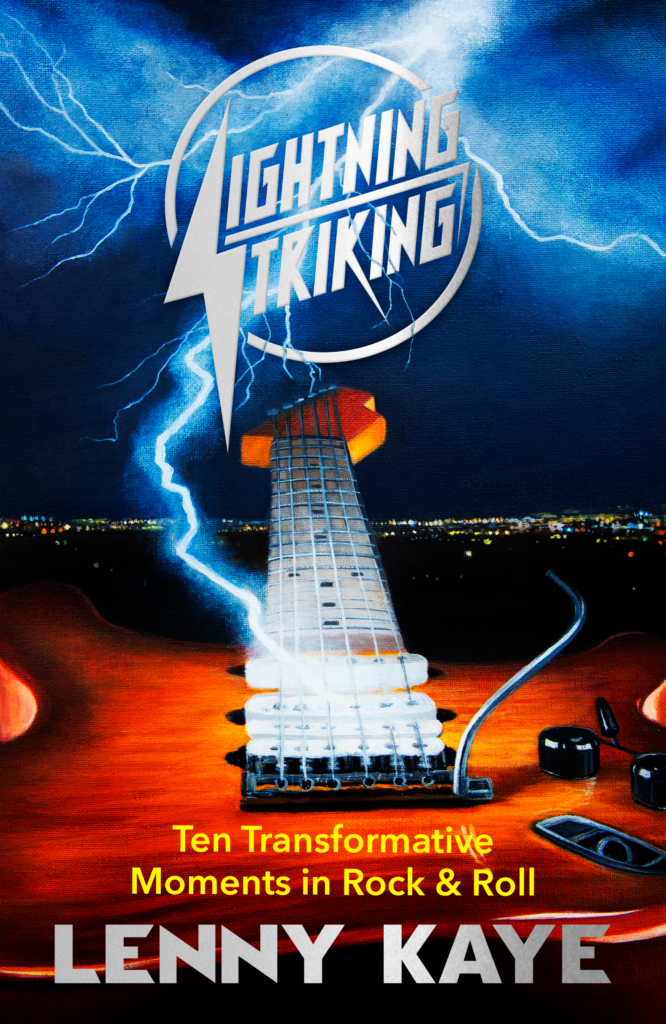

Lenny Kaye has been working on his new book, Lightning Striking: Ten Transformative Moments in Rock & Roll for half a decade but he has spent every second of his 74 years living at the heart of the counter-culture he has depicted. Over the course of almost 500 pages of entertaining and impeccably researched prose, Lenny anatomizes the story of the artform from Cleveland in 1952 to the ultimately tragic explosion of grunge – as arguably the last true innovation of the form in its truest sense – in Seattle. Along the way we are treated to a chronological and geographical tour of the global cities (Detroit, New York, London etc) at specific moments when rock & roll went through a kind of metamorphosis.

To accompany the announcement of the book last week we asked Lenny some questions about the book and his experience writing it. We are grateful to Lenny for responding at length and with such illuminating candour. Lightning Striking shapes a canon of a music that has repeatedly had a revolutionary impact, on adolescents, on popular culture and consciousness, and it does so in the style of a true disciple of the form, a living rock n roll legend himself.

White Rabbit: I know writers can sit with ideas for a long time as they percolate, take shape and blend before the writing process begins. Do you remember how and when you first had the idea to approach a history of rock & roll in this way?

Lenny Kaye: I’ve always been intrigued by the local, how regional styles develop and support, nurture, and release their eco-system into an awaiting musical universe. To trace where things come from, how time and space crossing can provide the building blocks of evolution. At one point in the early turn of the 1970s, while devising what would become the ur-garage text of Nuggets, I schemed a multi-volume anthology, each exploring a different city. The bands that grew within Los Angeles, San Francisco, Detroit, Chicago, and on across the country to New York and thence the world all seemed to have their distinctive spin on the music; geographic as well as temporal. There are always epicenters of creativity – ah, to be in Vienna in 1879 and have a coffee with Brahms at the Iger – and I often found myself wishing to be a part of these scenarios as they embarked on understanding the potentials of what they might be. As the years mounted in rock and roll’s scattershot history, it became my way of roadmapping the music’s evolution, history as cartography and time travel, generations measured from my own coming-of-age as audience and musician, like rings in a tree.

WR: The book is structured chronologically by ten cities, according to ten moments which you subjectively appoint as moments of ‘transformation’ in the artform of rock & roll? How did you choose these landmarks? I imagine you endlessly interrogating your record collection and auditioning perhaps a longlist of two dozen cities which ended up with these …

LK: The cities chose me, from the kind of music I have favored for any number of psychic reasons, the “rock band” combo that became my chosen vehicle for making music, and what seemed peak moments that mutated cellular change in the way rock regarded itself. I sought the dawning excitement of new, larger-than-life characters when they were much smaller; and the unfolding. There are many locals in the world, and I wish I could have visited more of them. Some I felt too much a stranger, needing a guide myself; for others I just ran out of time, and space. Name your city: I wish I was there, especially on a Saturday night as it begins to turn into Sunday, when things start getting rowdy.

WR: Riffing on this further, the book attempts a definition of what a certain kind of rock & roll canon might look like – to what extent is this a subjective Lenny Kaye take on the artform? What was the formula as you saw it for the most sublime rock & roll acts, performances and recordings that made it into the book?

LK: The formula is always transcendence, which makes it not a formula. I want to be taken by surprise, moved, inspired, the journey that is listening to a great song, or seeing someone burn incandescent on a stage. I don’t really care what kind of music or genre; though my home-team is rock and roll. Sometimes it’s most rewarding when it’s happened on unexpectedly, the b-side of a record, an out-of-bounds nightclub with someone singing their heart out to three people, a twist of fate that you follow down the rabbit hole of discovery. Music is subjective; that what makes it infinitely fascinating. Lightning Striking is my personal placement on rock’s family tree; but if you visit and see my record collection, you’ll see that the surrounding forest is what frames this book.

WR: Which begs the question, what does Lenny Kaye’s record collection look like?

LK: It’s a work-in-progress, which is what a record collection should be. It’s not overly completist; I hunt-and-gather what I like, and since over the course of these decades, I have spent much quality time in record stores (as well as literary emporiums), enhanced by global touring and an occupation that encourages accumulation, it doth overflow the shelving. A wall of vinyl albums, random piles of CDs, many treasured 45’s (it’s my favorite “storage medium”), 78s I can’t play, cylinders I’ve never been able to play, in varying stages of organization and good intentions. But it makes me happy.

WR: The book essentially covers 41 years (1952-1993). Why did you choose this end point – and apologies for asking but at least I will be one of the first to direct this inevitably dumb question your way.

LK: The book’s timeline covers the last half of the twentieth century, from when rock and roll moved from verb to noun, to when the internet began to dissolve localism within a new type of scenius: Brian Eno’s term for the collective energy that comes from “…the intelligence and the intuition of a whole cultural scene.” Musics do have an inbuilt lifespan, when they have been fully explored and assimilated, and their touchstone becomes one of interpretation rather than innovation. This doesn’t mean that their mode of making music is over; far from it. But like all lifeforms, including humans, there has to be a time when the new needs to be made way for, when instrument technologies and those who manipulate them want to make innovation theirs, when the definition changes. Now rock has become part of the many great wellsprings in which to sing the future; and I’m honored to have been a part of its coming of age.

WR: Do you believe rock & roll was the defining Modernist art form of the 20th century?

LK: I believe it’s just one of many mediums that have helped define the twentieth century: modernism in literature (Joyce, Faulkner, Dos Passos, and most science fiction, especially as embodied by Cordwainer Smith and Phillip K. Dick); film, for me especially the nouvelle vague as embodied by Godard and Sergio Leone’s Once Upon A Times; the visual arts, Picasso to Pollack to Warhol; and so many types of music – rhythm and blues and be-bop and country boogie and free jazz. The many forms of artistic expression, which makes us human.

WR: What is the legacy of rock & roll – how do we see it almost forty years after the book finishes, in Seattle?

LK: The legacy of rock and roll is that you can become it. It’s tricker than it looks but you can learn to turn up – the myth of self-realization – within moments, and then spend a lifetime figuring it out. As has been my privilege. Three decades on from its curtain call, with many resurrections yet to manifest, there’s so many great moments awaiting in the wilds that you can entertain yourself for eons. I always do.

WR: Are there cities you would have liked to include but felt didn’t include the narrative?

LK: So many cities, so little time. In the original proposal for Lightning Striking, I hoped to visit Athens/Minneapolis in the mid-eighties, where my friends live; and Manchester in the mid-80s, when rock begins to marry with the ecstasy of dance-techno. I would’ve liked to prologue in Chicago in 1953; my abiding love for reggae would have taken me to Kingston in the 1970s; and I was tempted to side-step to the crossroads of Bleecker and MacDougal in the Greenwich Village folk “revival,” though it only became rock in hindsight, too wary of electricity, protecting its turf. I can understand that. Sometimes you don’t want a scene to grow up, leave home. But all youth do.

WR: Which artists are absent in the book that you particular love but didn’t fit the thread, and why didn’t they?

LK: Great artists are beyond scene. Jimi Hendrix is a whole town in himself, and too often a star who shines too bright wreaks havoc on the local. You never know who will be annointed when a scene erupts, given the crown of thorns, entwining myth and sacrifice. Sometimes it doesn’t matter where you come from, and sometimes the coming from is what it’s all about. I made sure all my favorites had at least a name-check, if not a loving sentence.

WR: You lived a lot of the New York chapter but you make appearances in a few of the others. If you had to choose one city, and its scene, and legacy, to take with you, which would it be and why?

LK: I lived my scene, much to my surprise and good fortune. One night, somewhere in the mid-seventies, I was hanging outside CBGB. It was summer, and I looked at the bands and their gangs on the sidewalk, waiting to go on or just go on and on, and I thought this must’ve been what San Francisco was like at the Fillmore on a random night, or maybe the Cavern during a lunchtime concert, or … well, it didn’t matter. As long as you were there. I’ve been there – and not there – as many times as there are theres… Still looking for the next There.

WR: You and Patti are normally eternal tourers … what are your plans when this starts to cool off and ‘return to normal’?

LK: You mean the new paranormal. We’ll see how this 21st century unfolds, and we are as underway as can be. 100 years ago radio had yet to be mass-invented, movies were mute, and records were still recorded acoustically. This past year has accustomed us to communicating through screens, though it only seems to increase my desire to be among humans, to revel in the in-the-moment of live performance. There are postponed shows yet to be fulfilled, from Australia to the Royal Albert Hall, but I look forward to stopping into my locals – Tom Clark’s Treehouse every Sunday night at 2A in the East Village, the Johnny Thunders Birthday Bash every July at Bowery Electric, and… who knows? Perhaps that late night spontaneous jam when I pass through your city and am ready to commemorate the good times yet to come.

The lightning striking that is the playing of music.