During the pandemic I saw for the first time Jim Jarmusch’s epic film Only Lovers Left Alive, in which the vampire couple brilliantly played by Tilda Swinton and Tom Hiddleston try to deny their true nature during the entire film, partly by procuring blood through sophisticated means such as purchasing it from hospitals. Then of course, in the end, while desperate and starving, they resort to sucking the blood of a young couple kissing on the streets of Tangier.

Taking into account the risk of forcing an analogy too much, this scene seems to me to be fitting of what has taken place with the evolution of the pandemic in Mexico, especially since the end of the National Period of Safe Distance. This consisted mostly of a voluntary-yet-strict confinement and shutdown from March 23rd to May 30th, which was replaced by something called the New Normality, based on a very ambiguous and confusing system centered on colours mirroring those of a traffic light, which were in turn determined by the severity of the pandemic in the different states of Mexico. If on June 1st the number of casualties was a comparatively moderate 9,779 (in a country of 130,000 million inhabitants), and by every reasonable account both the authorities and the citizens had acted responsibly, in the ensuing three months the official death rate has skyrocketed to 70,183 as of September 11th. Although the epidemic curve now finally does seem to be flattening, a rate of around 500 new daily deaths means that the total number will ultimately be much higher.

Ever since the New Normality kicked in, there’s been a lot of chaos and confusion pertaining to the rules and, as one glance at a public space could slowly but surely confirm, social distancing norms became very relaxed almost immediately. However, in my opinion it’s a more complex issue than simply attributing it to what a Spanish journalist recently described as the “If I don’t die today, I die tomorrow” Mexican attitude – although many daily testimonies and YouTube videos strongly suggest that this has also been an element at play in the spiralling out of control of the pandemic. But it was perhaps a wishful proposition to think that a country with the astronomic rates of obesity, hypertension, diabetes and other deadly covid comorbidities such as Mexico, which also has a precarious and ravaged public health system, could emerge from the pandemic relatively unscathed. Also, in a similar vein to what other Latin American countries like Peru have experienced, the dependence of millions of people on the informal economy for their survival has turned the covid strategy into a sort of “pick your poison” proposition, by which if the strict lockdown had been kept on longer, it’d have inevitably meant more poverty and starvation.

But besides these deeply structural issues which for many are considered, to a certain extent, to be somewhat inevitable given the hardship of some aspects of the Mexican reality, it also seems to be the case that on a more performative public level, the country has reverted to its more profound nature. The pandemic has become a sort of omnipresent footnote which has given way to the usual array of political accusations and scandals, which have once again begun to dominate the news cycle. Thus, on July 8th, the very same day of a highly controversial visit from President López Obrador to Washington to meet with Donald Trump (the first time he’s exited Mexican soil in the two years of his presidency), a fugitive former Governor of Chihuahua called César Duarte was coincidentally captured in Miami by the US Marshals, in what was widely interpreted as a gift from Trump to López Obrador. A few weeks later Emilio Lozoya, the former head of Pemex, the national oil company, who had been arrested in Madrid since February was extradited back to Mexico. Upon his return he was for some undisclosed reason hospitalized and has now entered into a sort of witness protection programme. Videos of him incriminating the former president and his cronies have surfaced, and President López Obrador has announced there will be a public consultation so the Mexican people can decide whether the ex-presidents should be tried for corruption or not.

But lovers of Mexican folklore won’t be disappointed, as even while serving his jail sentence in a maximum security prison in the US, el Chapo Guzmán has managed to make pandemic news: his daughter Alejandrina Guzmán appeared in a video, distributing to elderly and disadvantaged people something called Chapodespensas (Chapoprovisions, or something like that) in boxes with el Chapo’s face printed on them, which contain toilet paper, corn, beans, sugar, cookies and more. They are handed out under strict covid-security measures (gloves, masks) and people can ask for them via Facebook. It is apparently a gesture to help those in need, but is also intended to promote Alejandrina’s fashion brand, called El Chapo 701.

This seeming reversion to conventional form even during a pandemic which has ravaged the entire world brings to mind a memorable scene from one of the best Mexican novels of all time, Under the Volcano, when Hugh, the Consul and Yvonne are travelling in a bus which stops suddenly, as there is a wounded dying man on the road. After Hugh unsuccessfully tries to do something about it and is forced by the Consul to climb back on the bus, he stares at some old women who have remained unmoved and silent through the whole ordeal: “There was no callousness in their faces, no cruelty. Death they knew, better than the law, and their memories were long. They sat ranked now, motionless, frozen, discussing nothing, without a word, turned to stone”.

Eduardo Rabasa

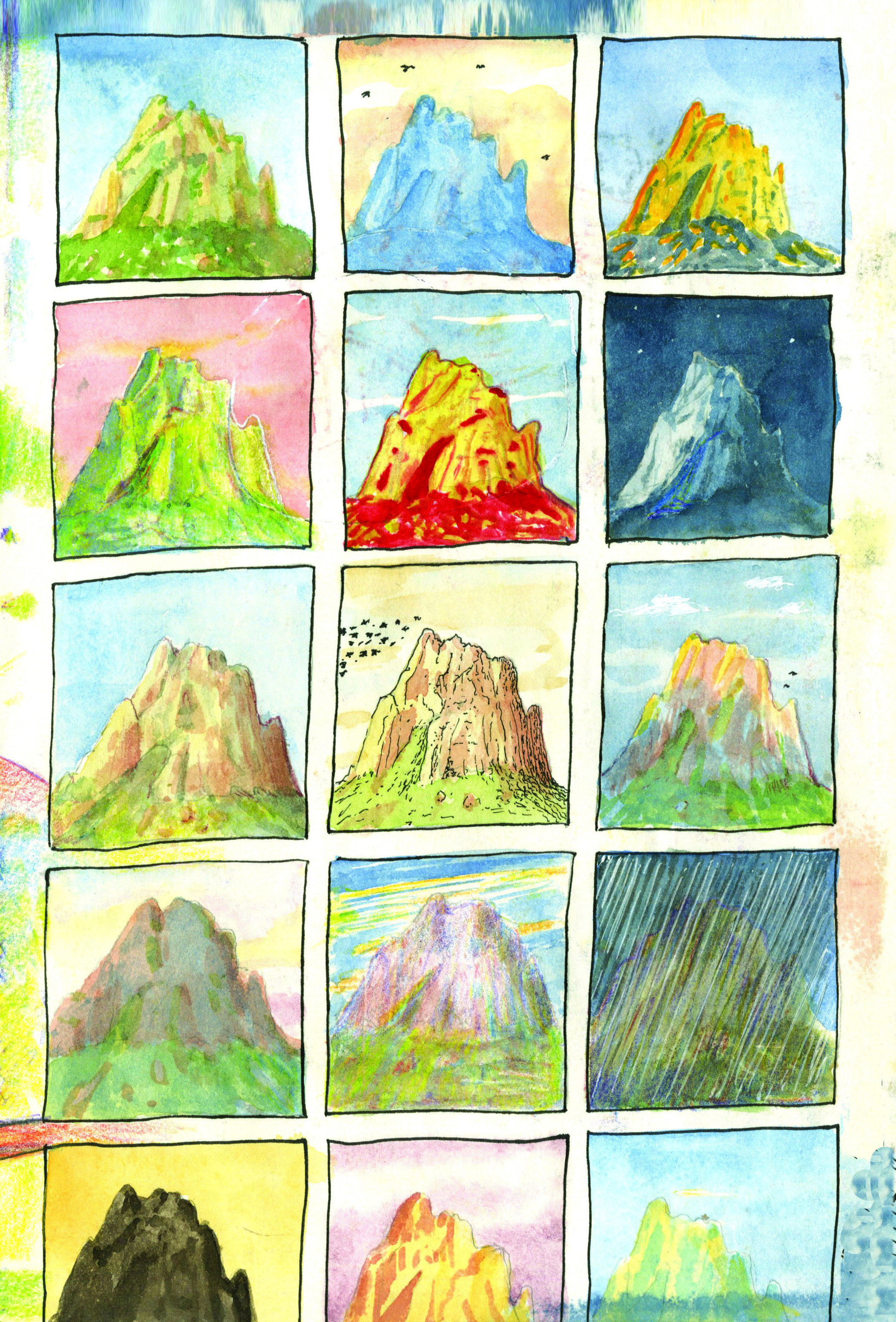

Artwork: Peter Kuper